In the 2011 fiscal year, 16,067 unaccompanied minors crossed the border from Mexico into the United States. By the end of the 2014 fiscal year, an estimated 90,000 unaccompanied minors will have crossed the border. The current number of illegal immigrant children has skyrocketed by 560 percent since 2011, with the expectation that that number will exponentially increase next year.

This recent surge in children has put Border Patrol and other agencies many, many times over capacity. There are simply too many children entering the country too quickly for Border Patrol to process and re-locate within the 48-hour window given to them by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act.

With number of immigrating Latin American children rising every day, the United States government must quickly find a way to deal with the 50,000 children that have entered the country so far this year, and the thousands of children that are sure to follow. Unfortunately, “quickly” is not a term generally associated with the current state of proceedings in the U.S. legislature. Furthermore, the Obama administration has been widely criticized for its response to the problem. Conservatives argue that President Obama’s policy of temporarily deferring the deportations sent a signal to thousands of Latin Americans that their children would be welcomed in the U.S. with open arms. Alternatively, Democrats contend that House Republicans are at fault for failing to pass last year’s immigration reform bill without offering their own plan for consideration.

On Tuesday, June 24th, the House Homeland Security Committee held a hearing on the immigration problem, which highlighted the partisan divide. During the hearing, Representative Candice Miller (R-MI) stated, “I think this humanitarian crisis can be laid directly at the feet of the President and his policy in 2012."

The reality of the situation disproves both arguments. As the Migration Policy Institute’s analysis states, “…there is no single cause. Instead, a confluence of different pull and push factors has contributed to the upsurge. Recent U.S. policies toward unaccompanied children, faltering economies and rising crime and gang activity in Central American countries, the desire for family reunification, and changing operations of smuggling networks have all converged."

Obama’s immigration policy contributes to this influx to the extent that smuggling rings have exploited the policy, telling children that there is a permiso (free pass) for minors crossing the border. Most Latin American children have little to no knowledge of actual U.S. policy.

Family reunification has always been a driver of illegal immigration and therefore cannot explain the extent of the recent increase—it must be some dramatic and new factor. So what has changed?

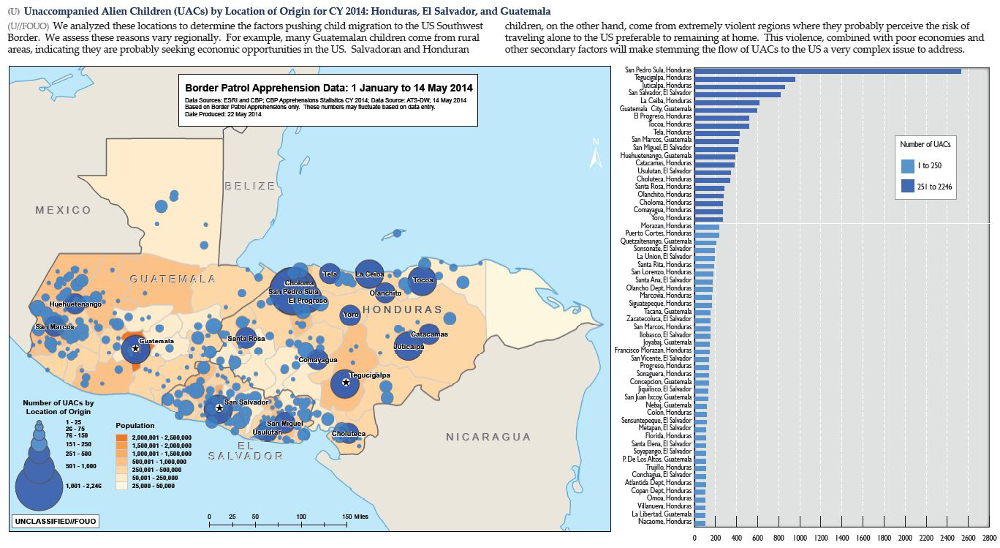

One startling clue comes from examining the child immigrants themselves. Before the 2012 fiscal year, 75 percent of immigrant children were Mexican, while in 2014, only 25 percent of immigrants are Mexican: 28 percent are Honduran, 24 percent are Guatemalan, and 21 perent are El Salvadoran. Suddenly, Mexicans are by far the minority.

This change derives largely from the spread of gang and cartel activity throughout the Central American region. Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala suffer among the top five highest homicide rates in the world; Honduras comes in at the top spot, with 90.4 homicides per 100,000, followed by El Salvador at number 4, with 41.2 per 100,000, and Guatemala in the fifth spot with 39.9 per 100,000 (in comparison, Mexico has about 22 homicides per 100,000 people and the United States has 5). In May 2014 alone, El Salvador, a small country with a population of only 6 million, saw more than 400 murders.

Economies falter when gangs take control, using any means necessary to grow in power. According to researchers specializing in Latin America, gangs have begun to use the school systems to generate new recruits. School directors and teachers are used to pressure children into joining a gang as foot soldiers. About a quarter of children already in the U.S. have reported deciding to leave after they were told that they must either begin using and selling drugs or die. Elizabeth Kennedy, a Fulbright Scholar based in El Salvador, interviewed 400 unaccompanied Salvadoran minors, discovering that about 60 percent of the children interviewed cited fear for their life as their impetus to leave.

Unaccompanied children often ride on the tops of trains to make it to the U.S., jumping on and off the moving train, named La Bestia or ‘The Beast’, when necessary to avoid security checkpoints and other obstacles. Not only is riding on top of a moving train dangerous on its own, but these train tops are governed by gangsters who are free to rob, rape, or kill whomever they choose.

With this in mind, both positions begin to fall apart. The promise of citizenship, however exaggerated by smuggling rings, is not enough on its own for tens of thousands of children to risk the treacherous journey between their homes and the United States. Furthermore, asylum requests to Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua (one of the poorest countries in the world), Panama, and Mexico from Hondurans, El Salvadorans, and Guatemalans have increased by 712 percent since 2009, according to UNHCR.

With these drivers of the crisis, the question now becomes, “How do we deal with this problem?” Proposed solutions range from the immediate (find space for increasingly large numbers of minors) to intermediate (expand legal avenues for children) and long-term options (improve regional security conditions) in the child immigration crisis.

Unfortunately, the same elements that lead to the breadth of opinion on the roots of this crisis have led to similarly divergent opinions as to solutions. At the House Committee hearing, Representative Miller argued: "Instead of increasing funding, we need to stop U.S. aid in the Centrals. I would say no more money from America until they step up to their own responsibilities and stop their citizens from migrating to the United States. [...] We need to whack our neighbors to make sure they understand they're not going to be taking our money. We are not the ATM machine."

In theory, ending the flow of monetary aid would spur lazy governments to begin to take a more active role, but most Central American governments do not possess the resources to enact and enforce anti-migration policies. They cannot keep up with the spending capabilities of the cartels, gangs, and smuggling rings; they are plagued by corruption; and their own people do not trust them.

Any attempt by the U.S. government to deal with the problem by tightening security or enacting new immigration policies will be like putting a Band-Aid on a broken leg—it will not fix the problem. In fact, deportations in the past have increased violence in Central American countries; adults that have joined Latin American gangs during their time in the U.S. generally add to conflict in their home countries after deportation and are often brutally killed at the first opportunity; children and adults escaping ultimatums likewise face death upon return. True reform can come only from an increased dedication to fighting gang and cartel activity within both the affected Central American countries and the U.S. itself.

On Tuesday, July 8th, President Obama requested more than $3.7 billion from Congress to address the deepening crisis. About $1.6 billion would go towards additional funding for immigration enforcement, including the prosecution of smugglers and additional drone crews to monitor the border, while the majority of the remaining $2.7 billion would go to Health and Human Services to provide shelter for children in the country. The administration also plans to spend roughly $161.5 million in aid to Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

Regardless of the ultimate policy, this crisis will likely persist for years. The process could be expedited if Congress were able to put aside bipartisan squabbles and accept the clear evidence of the increasing gang and cartel violence and pervasiveness as the root problems to be addressed. These children are not leaving their homes in such large numbers to come to the United States for trivial reasons—they are refugees. Desperation fuels their journey.

Photo: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (cc). Graph 1 and 2: Pew Research.

a global affairs media network

Partisan Divide Obscures Real Reasons Behind Influx of Immigrant Children

July 12, 2014

In the 2011 fiscal year, 16,067 unaccompanied minors crossed the border from Mexico into the United States. By the end of the 2014 fiscal year, an estimated 90,000 unaccompanied minors will have crossed the border. The current number of illegal immigrant children has skyrocketed by 560 percent since 2011, with the expectation that that number will exponentially increase next year.

This recent surge in children has put Border Patrol and other agencies many, many times over capacity. There are simply too many children entering the country too quickly for Border Patrol to process and re-locate within the 48-hour window given to them by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act.

With number of immigrating Latin American children rising every day, the United States government must quickly find a way to deal with the 50,000 children that have entered the country so far this year, and the thousands of children that are sure to follow. Unfortunately, “quickly” is not a term generally associated with the current state of proceedings in the U.S. legislature. Furthermore, the Obama administration has been widely criticized for its response to the problem. Conservatives argue that President Obama’s policy of temporarily deferring the deportations sent a signal to thousands of Latin Americans that their children would be welcomed in the U.S. with open arms. Alternatively, Democrats contend that House Republicans are at fault for failing to pass last year’s immigration reform bill without offering their own plan for consideration.

On Tuesday, June 24th, the House Homeland Security Committee held a hearing on the immigration problem, which highlighted the partisan divide. During the hearing, Representative Candice Miller (R-MI) stated, “I think this humanitarian crisis can be laid directly at the feet of the President and his policy in 2012."

The reality of the situation disproves both arguments. As the Migration Policy Institute’s analysis states, “…there is no single cause. Instead, a confluence of different pull and push factors has contributed to the upsurge. Recent U.S. policies toward unaccompanied children, faltering economies and rising crime and gang activity in Central American countries, the desire for family reunification, and changing operations of smuggling networks have all converged."

Obama’s immigration policy contributes to this influx to the extent that smuggling rings have exploited the policy, telling children that there is a permiso (free pass) for minors crossing the border. Most Latin American children have little to no knowledge of actual U.S. policy.

Family reunification has always been a driver of illegal immigration and therefore cannot explain the extent of the recent increase—it must be some dramatic and new factor. So what has changed?

One startling clue comes from examining the child immigrants themselves. Before the 2012 fiscal year, 75 percent of immigrant children were Mexican, while in 2014, only 25 percent of immigrants are Mexican: 28 percent are Honduran, 24 percent are Guatemalan, and 21 perent are El Salvadoran. Suddenly, Mexicans are by far the minority.

This change derives largely from the spread of gang and cartel activity throughout the Central American region. Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala suffer among the top five highest homicide rates in the world; Honduras comes in at the top spot, with 90.4 homicides per 100,000, followed by El Salvador at number 4, with 41.2 per 100,000, and Guatemala in the fifth spot with 39.9 per 100,000 (in comparison, Mexico has about 22 homicides per 100,000 people and the United States has 5). In May 2014 alone, El Salvador, a small country with a population of only 6 million, saw more than 400 murders.

Economies falter when gangs take control, using any means necessary to grow in power. According to researchers specializing in Latin America, gangs have begun to use the school systems to generate new recruits. School directors and teachers are used to pressure children into joining a gang as foot soldiers. About a quarter of children already in the U.S. have reported deciding to leave after they were told that they must either begin using and selling drugs or die. Elizabeth Kennedy, a Fulbright Scholar based in El Salvador, interviewed 400 unaccompanied Salvadoran minors, discovering that about 60 percent of the children interviewed cited fear for their life as their impetus to leave.

Unaccompanied children often ride on the tops of trains to make it to the U.S., jumping on and off the moving train, named La Bestia or ‘The Beast’, when necessary to avoid security checkpoints and other obstacles. Not only is riding on top of a moving train dangerous on its own, but these train tops are governed by gangsters who are free to rob, rape, or kill whomever they choose.

With this in mind, both positions begin to fall apart. The promise of citizenship, however exaggerated by smuggling rings, is not enough on its own for tens of thousands of children to risk the treacherous journey between their homes and the United States. Furthermore, asylum requests to Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua (one of the poorest countries in the world), Panama, and Mexico from Hondurans, El Salvadorans, and Guatemalans have increased by 712 percent since 2009, according to UNHCR.

With these drivers of the crisis, the question now becomes, “How do we deal with this problem?” Proposed solutions range from the immediate (find space for increasingly large numbers of minors) to intermediate (expand legal avenues for children) and long-term options (improve regional security conditions) in the child immigration crisis.

Unfortunately, the same elements that lead to the breadth of opinion on the roots of this crisis have led to similarly divergent opinions as to solutions. At the House Committee hearing, Representative Miller argued: "Instead of increasing funding, we need to stop U.S. aid in the Centrals. I would say no more money from America until they step up to their own responsibilities and stop their citizens from migrating to the United States. [...] We need to whack our neighbors to make sure they understand they're not going to be taking our money. We are not the ATM machine."

In theory, ending the flow of monetary aid would spur lazy governments to begin to take a more active role, but most Central American governments do not possess the resources to enact and enforce anti-migration policies. They cannot keep up with the spending capabilities of the cartels, gangs, and smuggling rings; they are plagued by corruption; and their own people do not trust them.

Any attempt by the U.S. government to deal with the problem by tightening security or enacting new immigration policies will be like putting a Band-Aid on a broken leg—it will not fix the problem. In fact, deportations in the past have increased violence in Central American countries; adults that have joined Latin American gangs during their time in the U.S. generally add to conflict in their home countries after deportation and are often brutally killed at the first opportunity; children and adults escaping ultimatums likewise face death upon return. True reform can come only from an increased dedication to fighting gang and cartel activity within both the affected Central American countries and the U.S. itself.

On Tuesday, July 8th, President Obama requested more than $3.7 billion from Congress to address the deepening crisis. About $1.6 billion would go towards additional funding for immigration enforcement, including the prosecution of smugglers and additional drone crews to monitor the border, while the majority of the remaining $2.7 billion would go to Health and Human Services to provide shelter for children in the country. The administration also plans to spend roughly $161.5 million in aid to Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

Regardless of the ultimate policy, this crisis will likely persist for years. The process could be expedited if Congress were able to put aside bipartisan squabbles and accept the clear evidence of the increasing gang and cartel violence and pervasiveness as the root problems to be addressed. These children are not leaving their homes in such large numbers to come to the United States for trivial reasons—they are refugees. Desperation fuels their journey.

Photo: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (cc). Graph 1 and 2: Pew Research.