.

Last year’s G7’s summit was the first in over twenty years with no Russian participation. As German Chancellor Angela Merkel hosts this year’s G7 Summit in June, Russia again is conspicuously absent. A year after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the G7’s suspension of Russia from its club of democratic, industrialized nations, the Group’s remaining members face a fundamental question: what is the role of Russia–and of the G7–in global affairs?

The G7 nations have declared that they will not participate in G8 meetings, pending the return of an environment in which the nations can hold ‘reasonable discussions.’ As with sanctions, excluding Russia from the G7 is a double-edged sword.

When the G7 met in The Hague to declare it would not attend the G8 meeting slated for Sochi in June, 2014, it excluded itself from a potentially useful forum for discussion while denting Russia’s pride and prestige. Aside from dialogue and prestige, however, the greatest victim–at least in the near-term–is the dream of integrating Russia into the club of developed, free-market, democratic nations.

The Aspirational Nature of the G8

The G8 was always more of an aspirational political project meant to bring Russia into the club of liberal democracies than a reflection of Russia’s true political and economic standing.

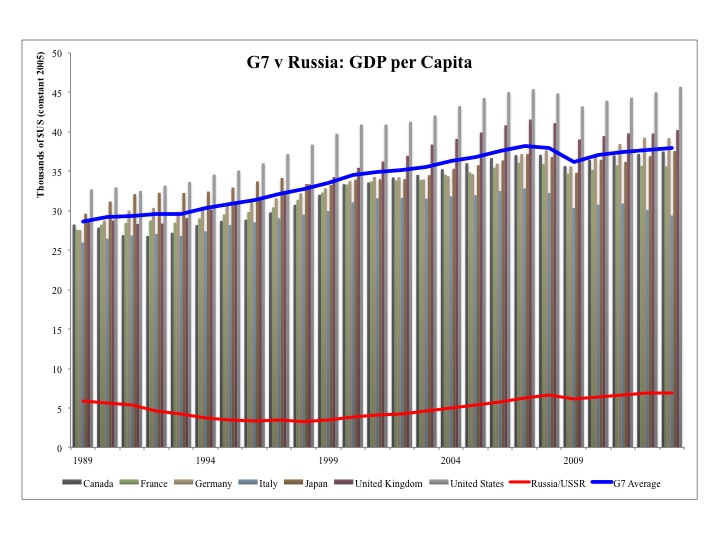

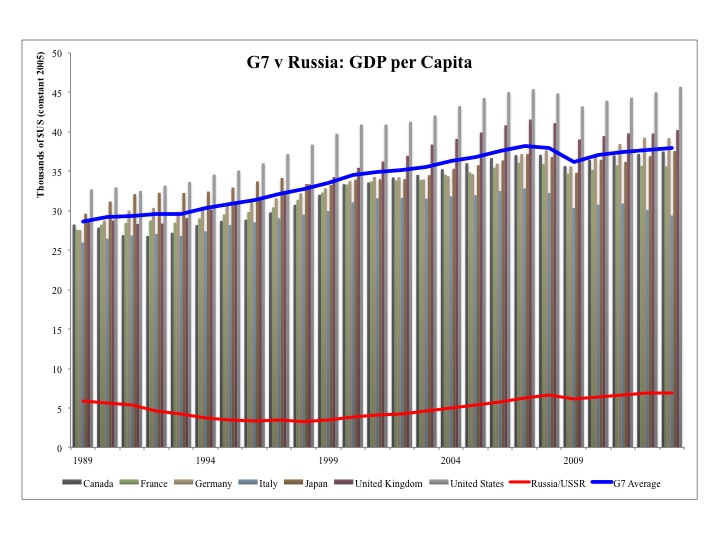

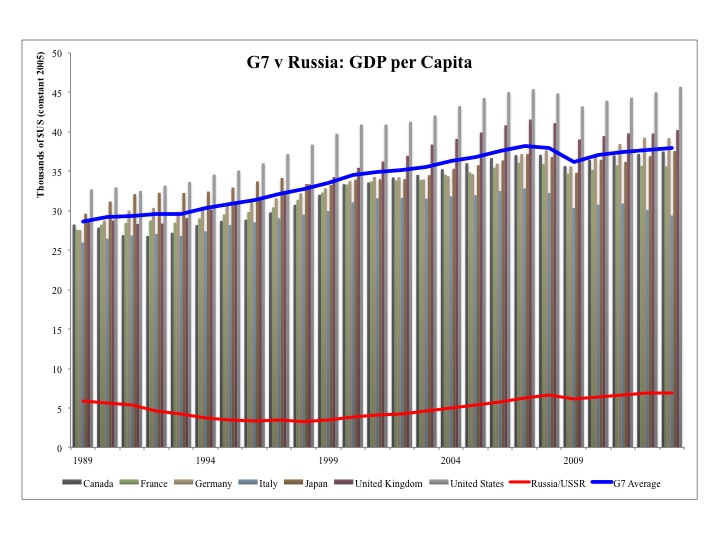

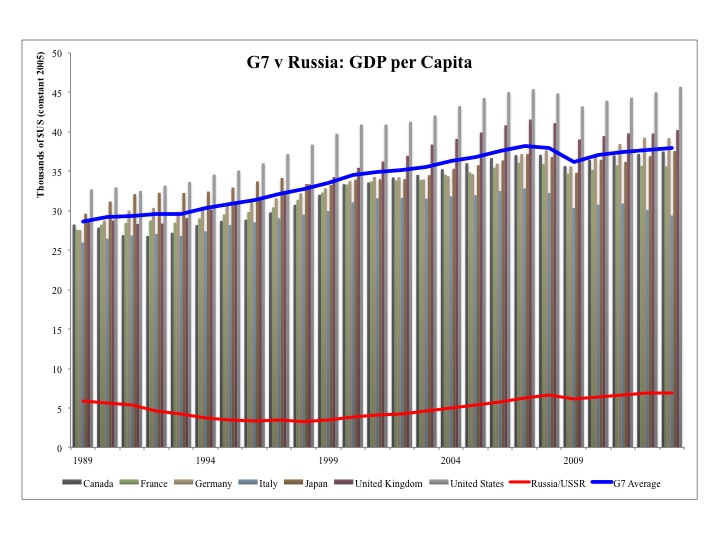

Since G7 cooperation with Moscow began in 1989, the average G7 GDP per capita has been more than five times that of Russia’s, and even at its most open and democratic, Russia was never on the same plane as the rest of the G7 in terms of democratic governance and freedom.

However, the G7 nations used cooperation as a carrot to coax Russia ever more firmly into their club. At the ‘Summit of the Arch’ in France in 1989, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev wrote to French President Mitterand on the importance of finding a ‘methodology’ for mutually beneficial macroeconomic coordination. In his post-Summit press conference, Mitterand did not exclude the possibility of the Soviet Union joining the G7.

Two years later, the Soviet Union participated in the 1991 London Summit, and from 1992 until 2013, Russia would participate in every G7/8 Summit. This strategy of ever-closer incorporation of Russia into their club seemed to work for the first decade (from 1989-1999), as Gorbachev and Yeltsin clearly sought integration with western institutions, such as the IMF, the World Bank, the EU, and NATO.

In constructing the G8, the G7 overlooked a number of Russia’s shortcomings in order to reward Moscow’s enthusiasm. In particular, President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair decided that G8 membership for Russia was needed to soften the blow of NATO’s 1997 expansion, acknowledge Yeltsin’s progress on democratic reforms, and reward his willingness to give up territorial claims on former Soviet states.

1999: End of the Millennium and the Honeymoon

Russia was invited to participate at the level of head of state at the Summit of Eight in Denver in 1997–though not as a full member, as the G7 released a separate communiqué on economic matters. The first meeting of the G8 did not take place until 1998 in Birmingham, and the first cracks appeared soon thereafter.

When NATO intervened in Kosovo in1999, the G8 declared its approval of draft UN Security Council Resolution language. Yet Russia clearly was not pleased, as Russian Foreign Minister noted during the press conference, “…there's no point in saying what I am more or less satisfied with.”

Meanwhile, many Russians were disillusioned with western institutions due to persistent economic hardship and their perpetually intoxicated pro-western President, Boris Yeltsin. Russia was ready for a new direction, and on New Year’s Eve in 1999, it got one when Yeltsin turned his presidency over to his young Prime Minister: Vladimir Putin.

At first, the G7 welcomed Putin’s ability to restore order and economic growth. However, it became clear that Putin–despite being economically liberal–did not share Yeltsin’s desire to import democratic values. Instead, he underscored the need for stability, security, and a role for Russia commensurate with its historical status as a great power.

The Emperor’s New Institutions

Despite the ideological rift–both politically, as the Kremlin consolidated political power in a single-party system, and economically, as efforts for diversifying Russia’s economy fizzled–the G7 nations continued to institutionalize Russia’s role in the G8, perhaps hoping that in so doing they could cement Russia into the liberal democratic world order. Thus, the G7 nations agreed to let Russia host its first G8 summit in 2006.

But the deepening discord kept bubbling up to the surface. In 2004, disagreement over U.S. involvement in Iraq and Russian interference in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution led to tense exchanges between the United States and Russia at the Georgia Island summit. The list of mutual grievances grew to include western objections to Russia’s use of natural gas as a political tool and Russian objections to U.S. ballistic missile defense. Relations hit a low point during the 2008 Russia-Georgia War.

Concurrent with deteriorating relations with the west, Russia was carving a niche for itself outside the Washington consensus. In 2009, Russia hailed the creation of the G20 as a more appropriate forum for deciding global economic issues. The Kremlin deemed this forum, as well as the BRICS summits of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, more in keeping with Russia’s new vision of itself as a key ‘pole’ in an increasingly multipolar world.

The End of the Affair

The Obama Administration’s effort to improve U.S.-Russian relations did not last long. Russian opposition to U.S. intervention in Libya, deteriorating human rights in Russia, Russian sheltering of whistleblower Edward Snowden and opposition to intervention in Syria culminated in the dual snubs of President Vladimir Putin boycotting the 2012 G8 summit in Camp David, followed by President Obama cancelling a planned bilateral meeting on the margins of the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg. Finally, in 2014, the G8 project–which had been limping along for years–collapsed under the weight of the war in Ukraine.

Future: Tense

The change in Russia’s policy introduced during Putin’s first presidency knocked Russia from the path of integration in the western world order. Though the heads of the G8 spent over a decade putting on brave faces and issuing rosy communiqués, the war in Ukraine has finally laid these differences bare.

With Russia out for now, the G7 may struggle to maintain its role as a pre-eminent voice on political and economic policy in the world. It should respond by ceasing to pretend that it is an inclusive forum for dialogue.

The G7 was founded as a group of like-minded, industrialized liberal democracies whose ability to come together to make policy on a range of issues – from fiscal and monetary adjustments and energy security to counter-terrorism – is better served when its members are like-minded states and not, as in the G8, a group of seven like-minded states and one spoiler.

Going forward, the G7 should focus its mission on providing a positive alternative to the rising tide of state capitalism and increasing authoritarianism. In short, it needs to become the club that a more democratic Russia – down the road – may want to join again.

Ann Dailey is an expert on the Eurasian region with experience in defense and energy. She has a Master's degree in International Economics from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a Bachelor's degree in Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian Affairs from the University of Illinois.

Since G7 cooperation with Moscow began in 1989, the average G7 GDP per capita has been more than five times that of Russia’s, and even at its most open and democratic, Russia was never on the same plane as the rest of the G7 in terms of democratic governance and freedom.

However, the G7 nations used cooperation as a carrot to coax Russia ever more firmly into their club. At the ‘Summit of the Arch’ in France in 1989, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev wrote to French President Mitterand on the importance of finding a ‘methodology’ for mutually beneficial macroeconomic coordination. In his post-Summit press conference, Mitterand did not exclude the possibility of the Soviet Union joining the G7.

Two years later, the Soviet Union participated in the 1991 London Summit, and from 1992 until 2013, Russia would participate in every G7/8 Summit. This strategy of ever-closer incorporation of Russia into their club seemed to work for the first decade (from 1989-1999), as Gorbachev and Yeltsin clearly sought integration with western institutions, such as the IMF, the World Bank, the EU, and NATO.

In constructing the G8, the G7 overlooked a number of Russia’s shortcomings in order to reward Moscow’s enthusiasm. In particular, President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair decided that G8 membership for Russia was needed to soften the blow of NATO’s 1997 expansion, acknowledge Yeltsin’s progress on democratic reforms, and reward his willingness to give up territorial claims on former Soviet states.

1999: End of the Millennium and the Honeymoon

Russia was invited to participate at the level of head of state at the Summit of Eight in Denver in 1997–though not as a full member, as the G7 released a separate communiqué on economic matters. The first meeting of the G8 did not take place until 1998 in Birmingham, and the first cracks appeared soon thereafter.

When NATO intervened in Kosovo in1999, the G8 declared its approval of draft UN Security Council Resolution language. Yet Russia clearly was not pleased, as Russian Foreign Minister noted during the press conference, “…there's no point in saying what I am more or less satisfied with.”

Meanwhile, many Russians were disillusioned with western institutions due to persistent economic hardship and their perpetually intoxicated pro-western President, Boris Yeltsin. Russia was ready for a new direction, and on New Year’s Eve in 1999, it got one when Yeltsin turned his presidency over to his young Prime Minister: Vladimir Putin.

At first, the G7 welcomed Putin’s ability to restore order and economic growth. However, it became clear that Putin–despite being economically liberal–did not share Yeltsin’s desire to import democratic values. Instead, he underscored the need for stability, security, and a role for Russia commensurate with its historical status as a great power.

The Emperor’s New Institutions

Despite the ideological rift–both politically, as the Kremlin consolidated political power in a single-party system, and economically, as efforts for diversifying Russia’s economy fizzled–the G7 nations continued to institutionalize Russia’s role in the G8, perhaps hoping that in so doing they could cement Russia into the liberal democratic world order. Thus, the G7 nations agreed to let Russia host its first G8 summit in 2006.

But the deepening discord kept bubbling up to the surface. In 2004, disagreement over U.S. involvement in Iraq and Russian interference in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution led to tense exchanges between the United States and Russia at the Georgia Island summit. The list of mutual grievances grew to include western objections to Russia’s use of natural gas as a political tool and Russian objections to U.S. ballistic missile defense. Relations hit a low point during the 2008 Russia-Georgia War.

Concurrent with deteriorating relations with the west, Russia was carving a niche for itself outside the Washington consensus. In 2009, Russia hailed the creation of the G20 as a more appropriate forum for deciding global economic issues. The Kremlin deemed this forum, as well as the BRICS summits of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, more in keeping with Russia’s new vision of itself as a key ‘pole’ in an increasingly multipolar world.

The End of the Affair

The Obama Administration’s effort to improve U.S.-Russian relations did not last long. Russian opposition to U.S. intervention in Libya, deteriorating human rights in Russia, Russian sheltering of whistleblower Edward Snowden and opposition to intervention in Syria culminated in the dual snubs of President Vladimir Putin boycotting the 2012 G8 summit in Camp David, followed by President Obama cancelling a planned bilateral meeting on the margins of the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg. Finally, in 2014, the G8 project–which had been limping along for years–collapsed under the weight of the war in Ukraine.

Future: Tense

The change in Russia’s policy introduced during Putin’s first presidency knocked Russia from the path of integration in the western world order. Though the heads of the G8 spent over a decade putting on brave faces and issuing rosy communiqués, the war in Ukraine has finally laid these differences bare.

With Russia out for now, the G7 may struggle to maintain its role as a pre-eminent voice on political and economic policy in the world. It should respond by ceasing to pretend that it is an inclusive forum for dialogue.

The G7 was founded as a group of like-minded, industrialized liberal democracies whose ability to come together to make policy on a range of issues – from fiscal and monetary adjustments and energy security to counter-terrorism – is better served when its members are like-minded states and not, as in the G8, a group of seven like-minded states and one spoiler.

Going forward, the G7 should focus its mission on providing a positive alternative to the rising tide of state capitalism and increasing authoritarianism. In short, it needs to become the club that a more democratic Russia – down the road – may want to join again.

Ann Dailey is an expert on the Eurasian region with experience in defense and energy. She has a Master's degree in International Economics from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a Bachelor's degree in Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian Affairs from the University of Illinois.

Since G7 cooperation with Moscow began in 1989, the average G7 GDP per capita has been more than five times that of Russia’s, and even at its most open and democratic, Russia was never on the same plane as the rest of the G7 in terms of democratic governance and freedom.

However, the G7 nations used cooperation as a carrot to coax Russia ever more firmly into their club. At the ‘Summit of the Arch’ in France in 1989, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev wrote to French President Mitterand on the importance of finding a ‘methodology’ for mutually beneficial macroeconomic coordination. In his post-Summit press conference, Mitterand did not exclude the possibility of the Soviet Union joining the G7.

Two years later, the Soviet Union participated in the 1991 London Summit, and from 1992 until 2013, Russia would participate in every G7/8 Summit. This strategy of ever-closer incorporation of Russia into their club seemed to work for the first decade (from 1989-1999), as Gorbachev and Yeltsin clearly sought integration with western institutions, such as the IMF, the World Bank, the EU, and NATO.

In constructing the G8, the G7 overlooked a number of Russia’s shortcomings in order to reward Moscow’s enthusiasm. In particular, President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair decided that G8 membership for Russia was needed to soften the blow of NATO’s 1997 expansion, acknowledge Yeltsin’s progress on democratic reforms, and reward his willingness to give up territorial claims on former Soviet states.

1999: End of the Millennium and the Honeymoon

Russia was invited to participate at the level of head of state at the Summit of Eight in Denver in 1997–though not as a full member, as the G7 released a separate communiqué on economic matters. The first meeting of the G8 did not take place until 1998 in Birmingham, and the first cracks appeared soon thereafter.

When NATO intervened in Kosovo in1999, the G8 declared its approval of draft UN Security Council Resolution language. Yet Russia clearly was not pleased, as Russian Foreign Minister noted during the press conference, “…there's no point in saying what I am more or less satisfied with.”

Meanwhile, many Russians were disillusioned with western institutions due to persistent economic hardship and their perpetually intoxicated pro-western President, Boris Yeltsin. Russia was ready for a new direction, and on New Year’s Eve in 1999, it got one when Yeltsin turned his presidency over to his young Prime Minister: Vladimir Putin.

At first, the G7 welcomed Putin’s ability to restore order and economic growth. However, it became clear that Putin–despite being economically liberal–did not share Yeltsin’s desire to import democratic values. Instead, he underscored the need for stability, security, and a role for Russia commensurate with its historical status as a great power.

The Emperor’s New Institutions

Despite the ideological rift–both politically, as the Kremlin consolidated political power in a single-party system, and economically, as efforts for diversifying Russia’s economy fizzled–the G7 nations continued to institutionalize Russia’s role in the G8, perhaps hoping that in so doing they could cement Russia into the liberal democratic world order. Thus, the G7 nations agreed to let Russia host its first G8 summit in 2006.

But the deepening discord kept bubbling up to the surface. In 2004, disagreement over U.S. involvement in Iraq and Russian interference in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution led to tense exchanges between the United States and Russia at the Georgia Island summit. The list of mutual grievances grew to include western objections to Russia’s use of natural gas as a political tool and Russian objections to U.S. ballistic missile defense. Relations hit a low point during the 2008 Russia-Georgia War.

Concurrent with deteriorating relations with the west, Russia was carving a niche for itself outside the Washington consensus. In 2009, Russia hailed the creation of the G20 as a more appropriate forum for deciding global economic issues. The Kremlin deemed this forum, as well as the BRICS summits of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, more in keeping with Russia’s new vision of itself as a key ‘pole’ in an increasingly multipolar world.

The End of the Affair

The Obama Administration’s effort to improve U.S.-Russian relations did not last long. Russian opposition to U.S. intervention in Libya, deteriorating human rights in Russia, Russian sheltering of whistleblower Edward Snowden and opposition to intervention in Syria culminated in the dual snubs of President Vladimir Putin boycotting the 2012 G8 summit in Camp David, followed by President Obama cancelling a planned bilateral meeting on the margins of the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg. Finally, in 2014, the G8 project–which had been limping along for years–collapsed under the weight of the war in Ukraine.

Future: Tense

The change in Russia’s policy introduced during Putin’s first presidency knocked Russia from the path of integration in the western world order. Though the heads of the G8 spent over a decade putting on brave faces and issuing rosy communiqués, the war in Ukraine has finally laid these differences bare.

With Russia out for now, the G7 may struggle to maintain its role as a pre-eminent voice on political and economic policy in the world. It should respond by ceasing to pretend that it is an inclusive forum for dialogue.

The G7 was founded as a group of like-minded, industrialized liberal democracies whose ability to come together to make policy on a range of issues – from fiscal and monetary adjustments and energy security to counter-terrorism – is better served when its members are like-minded states and not, as in the G8, a group of seven like-minded states and one spoiler.

Going forward, the G7 should focus its mission on providing a positive alternative to the rising tide of state capitalism and increasing authoritarianism. In short, it needs to become the club that a more democratic Russia – down the road – may want to join again.

Ann Dailey is an expert on the Eurasian region with experience in defense and energy. She has a Master's degree in International Economics from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a Bachelor's degree in Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian Affairs from the University of Illinois.

Since G7 cooperation with Moscow began in 1989, the average G7 GDP per capita has been more than five times that of Russia’s, and even at its most open and democratic, Russia was never on the same plane as the rest of the G7 in terms of democratic governance and freedom.

However, the G7 nations used cooperation as a carrot to coax Russia ever more firmly into their club. At the ‘Summit of the Arch’ in France in 1989, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev wrote to French President Mitterand on the importance of finding a ‘methodology’ for mutually beneficial macroeconomic coordination. In his post-Summit press conference, Mitterand did not exclude the possibility of the Soviet Union joining the G7.

Two years later, the Soviet Union participated in the 1991 London Summit, and from 1992 until 2013, Russia would participate in every G7/8 Summit. This strategy of ever-closer incorporation of Russia into their club seemed to work for the first decade (from 1989-1999), as Gorbachev and Yeltsin clearly sought integration with western institutions, such as the IMF, the World Bank, the EU, and NATO.

In constructing the G8, the G7 overlooked a number of Russia’s shortcomings in order to reward Moscow’s enthusiasm. In particular, President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair decided that G8 membership for Russia was needed to soften the blow of NATO’s 1997 expansion, acknowledge Yeltsin’s progress on democratic reforms, and reward his willingness to give up territorial claims on former Soviet states.

1999: End of the Millennium and the Honeymoon

Russia was invited to participate at the level of head of state at the Summit of Eight in Denver in 1997–though not as a full member, as the G7 released a separate communiqué on economic matters. The first meeting of the G8 did not take place until 1998 in Birmingham, and the first cracks appeared soon thereafter.

When NATO intervened in Kosovo in1999, the G8 declared its approval of draft UN Security Council Resolution language. Yet Russia clearly was not pleased, as Russian Foreign Minister noted during the press conference, “…there's no point in saying what I am more or less satisfied with.”

Meanwhile, many Russians were disillusioned with western institutions due to persistent economic hardship and their perpetually intoxicated pro-western President, Boris Yeltsin. Russia was ready for a new direction, and on New Year’s Eve in 1999, it got one when Yeltsin turned his presidency over to his young Prime Minister: Vladimir Putin.

At first, the G7 welcomed Putin’s ability to restore order and economic growth. However, it became clear that Putin–despite being economically liberal–did not share Yeltsin’s desire to import democratic values. Instead, he underscored the need for stability, security, and a role for Russia commensurate with its historical status as a great power.

The Emperor’s New Institutions

Despite the ideological rift–both politically, as the Kremlin consolidated political power in a single-party system, and economically, as efforts for diversifying Russia’s economy fizzled–the G7 nations continued to institutionalize Russia’s role in the G8, perhaps hoping that in so doing they could cement Russia into the liberal democratic world order. Thus, the G7 nations agreed to let Russia host its first G8 summit in 2006.

But the deepening discord kept bubbling up to the surface. In 2004, disagreement over U.S. involvement in Iraq and Russian interference in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution led to tense exchanges between the United States and Russia at the Georgia Island summit. The list of mutual grievances grew to include western objections to Russia’s use of natural gas as a political tool and Russian objections to U.S. ballistic missile defense. Relations hit a low point during the 2008 Russia-Georgia War.

Concurrent with deteriorating relations with the west, Russia was carving a niche for itself outside the Washington consensus. In 2009, Russia hailed the creation of the G20 as a more appropriate forum for deciding global economic issues. The Kremlin deemed this forum, as well as the BRICS summits of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, more in keeping with Russia’s new vision of itself as a key ‘pole’ in an increasingly multipolar world.

The End of the Affair

The Obama Administration’s effort to improve U.S.-Russian relations did not last long. Russian opposition to U.S. intervention in Libya, deteriorating human rights in Russia, Russian sheltering of whistleblower Edward Snowden and opposition to intervention in Syria culminated in the dual snubs of President Vladimir Putin boycotting the 2012 G8 summit in Camp David, followed by President Obama cancelling a planned bilateral meeting on the margins of the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg. Finally, in 2014, the G8 project–which had been limping along for years–collapsed under the weight of the war in Ukraine.

Future: Tense

The change in Russia’s policy introduced during Putin’s first presidency knocked Russia from the path of integration in the western world order. Though the heads of the G8 spent over a decade putting on brave faces and issuing rosy communiqués, the war in Ukraine has finally laid these differences bare.

With Russia out for now, the G7 may struggle to maintain its role as a pre-eminent voice on political and economic policy in the world. It should respond by ceasing to pretend that it is an inclusive forum for dialogue.

The G7 was founded as a group of like-minded, industrialized liberal democracies whose ability to come together to make policy on a range of issues – from fiscal and monetary adjustments and energy security to counter-terrorism – is better served when its members are like-minded states and not, as in the G8, a group of seven like-minded states and one spoiler.

Going forward, the G7 should focus its mission on providing a positive alternative to the rising tide of state capitalism and increasing authoritarianism. In short, it needs to become the club that a more democratic Russia – down the road – may want to join again.

Ann Dailey is an expert on the Eurasian region with experience in defense and energy. She has a Master's degree in International Economics from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a Bachelor's degree in Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian Affairs from the University of Illinois.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.

a global affairs media network

A Failed Political Exercise

|

June 8, 2015

Last year’s G7’s summit was the first in over twenty years with no Russian participation. As German Chancellor Angela Merkel hosts this year’s G7 Summit in June, Russia again is conspicuously absent. A year after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the G7’s suspension of Russia from its club of democratic, industrialized nations, the Group’s remaining members face a fundamental question: what is the role of Russia–and of the G7–in global affairs?

The G7 nations have declared that they will not participate in G8 meetings, pending the return of an environment in which the nations can hold ‘reasonable discussions.’ As with sanctions, excluding Russia from the G7 is a double-edged sword.

When the G7 met in The Hague to declare it would not attend the G8 meeting slated for Sochi in June, 2014, it excluded itself from a potentially useful forum for discussion while denting Russia’s pride and prestige. Aside from dialogue and prestige, however, the greatest victim–at least in the near-term–is the dream of integrating Russia into the club of developed, free-market, democratic nations.

The Aspirational Nature of the G8

The G8 was always more of an aspirational political project meant to bring Russia into the club of liberal democracies than a reflection of Russia’s true political and economic standing.

Since G7 cooperation with Moscow began in 1989, the average G7 GDP per capita has been more than five times that of Russia’s, and even at its most open and democratic, Russia was never on the same plane as the rest of the G7 in terms of democratic governance and freedom.

However, the G7 nations used cooperation as a carrot to coax Russia ever more firmly into their club. At the ‘Summit of the Arch’ in France in 1989, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev wrote to French President Mitterand on the importance of finding a ‘methodology’ for mutually beneficial macroeconomic coordination. In his post-Summit press conference, Mitterand did not exclude the possibility of the Soviet Union joining the G7.

Two years later, the Soviet Union participated in the 1991 London Summit, and from 1992 until 2013, Russia would participate in every G7/8 Summit. This strategy of ever-closer incorporation of Russia into their club seemed to work for the first decade (from 1989-1999), as Gorbachev and Yeltsin clearly sought integration with western institutions, such as the IMF, the World Bank, the EU, and NATO.

In constructing the G8, the G7 overlooked a number of Russia’s shortcomings in order to reward Moscow’s enthusiasm. In particular, President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair decided that G8 membership for Russia was needed to soften the blow of NATO’s 1997 expansion, acknowledge Yeltsin’s progress on democratic reforms, and reward his willingness to give up territorial claims on former Soviet states.

1999: End of the Millennium and the Honeymoon

Russia was invited to participate at the level of head of state at the Summit of Eight in Denver in 1997–though not as a full member, as the G7 released a separate communiqué on economic matters. The first meeting of the G8 did not take place until 1998 in Birmingham, and the first cracks appeared soon thereafter.

When NATO intervened in Kosovo in1999, the G8 declared its approval of draft UN Security Council Resolution language. Yet Russia clearly was not pleased, as Russian Foreign Minister noted during the press conference, “…there's no point in saying what I am more or less satisfied with.”

Meanwhile, many Russians were disillusioned with western institutions due to persistent economic hardship and their perpetually intoxicated pro-western President, Boris Yeltsin. Russia was ready for a new direction, and on New Year’s Eve in 1999, it got one when Yeltsin turned his presidency over to his young Prime Minister: Vladimir Putin.

At first, the G7 welcomed Putin’s ability to restore order and economic growth. However, it became clear that Putin–despite being economically liberal–did not share Yeltsin’s desire to import democratic values. Instead, he underscored the need for stability, security, and a role for Russia commensurate with its historical status as a great power.

The Emperor’s New Institutions

Despite the ideological rift–both politically, as the Kremlin consolidated political power in a single-party system, and economically, as efforts for diversifying Russia’s economy fizzled–the G7 nations continued to institutionalize Russia’s role in the G8, perhaps hoping that in so doing they could cement Russia into the liberal democratic world order. Thus, the G7 nations agreed to let Russia host its first G8 summit in 2006.

But the deepening discord kept bubbling up to the surface. In 2004, disagreement over U.S. involvement in Iraq and Russian interference in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution led to tense exchanges between the United States and Russia at the Georgia Island summit. The list of mutual grievances grew to include western objections to Russia’s use of natural gas as a political tool and Russian objections to U.S. ballistic missile defense. Relations hit a low point during the 2008 Russia-Georgia War.

Concurrent with deteriorating relations with the west, Russia was carving a niche for itself outside the Washington consensus. In 2009, Russia hailed the creation of the G20 as a more appropriate forum for deciding global economic issues. The Kremlin deemed this forum, as well as the BRICS summits of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, more in keeping with Russia’s new vision of itself as a key ‘pole’ in an increasingly multipolar world.

The End of the Affair

The Obama Administration’s effort to improve U.S.-Russian relations did not last long. Russian opposition to U.S. intervention in Libya, deteriorating human rights in Russia, Russian sheltering of whistleblower Edward Snowden and opposition to intervention in Syria culminated in the dual snubs of President Vladimir Putin boycotting the 2012 G8 summit in Camp David, followed by President Obama cancelling a planned bilateral meeting on the margins of the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg. Finally, in 2014, the G8 project–which had been limping along for years–collapsed under the weight of the war in Ukraine.

Future: Tense

The change in Russia’s policy introduced during Putin’s first presidency knocked Russia from the path of integration in the western world order. Though the heads of the G8 spent over a decade putting on brave faces and issuing rosy communiqués, the war in Ukraine has finally laid these differences bare.

With Russia out for now, the G7 may struggle to maintain its role as a pre-eminent voice on political and economic policy in the world. It should respond by ceasing to pretend that it is an inclusive forum for dialogue.

The G7 was founded as a group of like-minded, industrialized liberal democracies whose ability to come together to make policy on a range of issues – from fiscal and monetary adjustments and energy security to counter-terrorism – is better served when its members are like-minded states and not, as in the G8, a group of seven like-minded states and one spoiler.

Going forward, the G7 should focus its mission on providing a positive alternative to the rising tide of state capitalism and increasing authoritarianism. In short, it needs to become the club that a more democratic Russia – down the road – may want to join again.

Ann Dailey is an expert on the Eurasian region with experience in defense and energy. She has a Master's degree in International Economics from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a Bachelor's degree in Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian Affairs from the University of Illinois.

Since G7 cooperation with Moscow began in 1989, the average G7 GDP per capita has been more than five times that of Russia’s, and even at its most open and democratic, Russia was never on the same plane as the rest of the G7 in terms of democratic governance and freedom.

However, the G7 nations used cooperation as a carrot to coax Russia ever more firmly into their club. At the ‘Summit of the Arch’ in France in 1989, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev wrote to French President Mitterand on the importance of finding a ‘methodology’ for mutually beneficial macroeconomic coordination. In his post-Summit press conference, Mitterand did not exclude the possibility of the Soviet Union joining the G7.

Two years later, the Soviet Union participated in the 1991 London Summit, and from 1992 until 2013, Russia would participate in every G7/8 Summit. This strategy of ever-closer incorporation of Russia into their club seemed to work for the first decade (from 1989-1999), as Gorbachev and Yeltsin clearly sought integration with western institutions, such as the IMF, the World Bank, the EU, and NATO.

In constructing the G8, the G7 overlooked a number of Russia’s shortcomings in order to reward Moscow’s enthusiasm. In particular, President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair decided that G8 membership for Russia was needed to soften the blow of NATO’s 1997 expansion, acknowledge Yeltsin’s progress on democratic reforms, and reward his willingness to give up territorial claims on former Soviet states.

1999: End of the Millennium and the Honeymoon

Russia was invited to participate at the level of head of state at the Summit of Eight in Denver in 1997–though not as a full member, as the G7 released a separate communiqué on economic matters. The first meeting of the G8 did not take place until 1998 in Birmingham, and the first cracks appeared soon thereafter.

When NATO intervened in Kosovo in1999, the G8 declared its approval of draft UN Security Council Resolution language. Yet Russia clearly was not pleased, as Russian Foreign Minister noted during the press conference, “…there's no point in saying what I am more or less satisfied with.”

Meanwhile, many Russians were disillusioned with western institutions due to persistent economic hardship and their perpetually intoxicated pro-western President, Boris Yeltsin. Russia was ready for a new direction, and on New Year’s Eve in 1999, it got one when Yeltsin turned his presidency over to his young Prime Minister: Vladimir Putin.

At first, the G7 welcomed Putin’s ability to restore order and economic growth. However, it became clear that Putin–despite being economically liberal–did not share Yeltsin’s desire to import democratic values. Instead, he underscored the need for stability, security, and a role for Russia commensurate with its historical status as a great power.

The Emperor’s New Institutions

Despite the ideological rift–both politically, as the Kremlin consolidated political power in a single-party system, and economically, as efforts for diversifying Russia’s economy fizzled–the G7 nations continued to institutionalize Russia’s role in the G8, perhaps hoping that in so doing they could cement Russia into the liberal democratic world order. Thus, the G7 nations agreed to let Russia host its first G8 summit in 2006.

But the deepening discord kept bubbling up to the surface. In 2004, disagreement over U.S. involvement in Iraq and Russian interference in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution led to tense exchanges between the United States and Russia at the Georgia Island summit. The list of mutual grievances grew to include western objections to Russia’s use of natural gas as a political tool and Russian objections to U.S. ballistic missile defense. Relations hit a low point during the 2008 Russia-Georgia War.

Concurrent with deteriorating relations with the west, Russia was carving a niche for itself outside the Washington consensus. In 2009, Russia hailed the creation of the G20 as a more appropriate forum for deciding global economic issues. The Kremlin deemed this forum, as well as the BRICS summits of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, more in keeping with Russia’s new vision of itself as a key ‘pole’ in an increasingly multipolar world.

The End of the Affair

The Obama Administration’s effort to improve U.S.-Russian relations did not last long. Russian opposition to U.S. intervention in Libya, deteriorating human rights in Russia, Russian sheltering of whistleblower Edward Snowden and opposition to intervention in Syria culminated in the dual snubs of President Vladimir Putin boycotting the 2012 G8 summit in Camp David, followed by President Obama cancelling a planned bilateral meeting on the margins of the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg. Finally, in 2014, the G8 project–which had been limping along for years–collapsed under the weight of the war in Ukraine.

Future: Tense

The change in Russia’s policy introduced during Putin’s first presidency knocked Russia from the path of integration in the western world order. Though the heads of the G8 spent over a decade putting on brave faces and issuing rosy communiqués, the war in Ukraine has finally laid these differences bare.

With Russia out for now, the G7 may struggle to maintain its role as a pre-eminent voice on political and economic policy in the world. It should respond by ceasing to pretend that it is an inclusive forum for dialogue.

The G7 was founded as a group of like-minded, industrialized liberal democracies whose ability to come together to make policy on a range of issues – from fiscal and monetary adjustments and energy security to counter-terrorism – is better served when its members are like-minded states and not, as in the G8, a group of seven like-minded states and one spoiler.

Going forward, the G7 should focus its mission on providing a positive alternative to the rising tide of state capitalism and increasing authoritarianism. In short, it needs to become the club that a more democratic Russia – down the road – may want to join again.

Ann Dailey is an expert on the Eurasian region with experience in defense and energy. She has a Master's degree in International Economics from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a Bachelor's degree in Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian Affairs from the University of Illinois.

Since G7 cooperation with Moscow began in 1989, the average G7 GDP per capita has been more than five times that of Russia’s, and even at its most open and democratic, Russia was never on the same plane as the rest of the G7 in terms of democratic governance and freedom.

However, the G7 nations used cooperation as a carrot to coax Russia ever more firmly into their club. At the ‘Summit of the Arch’ in France in 1989, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev wrote to French President Mitterand on the importance of finding a ‘methodology’ for mutually beneficial macroeconomic coordination. In his post-Summit press conference, Mitterand did not exclude the possibility of the Soviet Union joining the G7.

Two years later, the Soviet Union participated in the 1991 London Summit, and from 1992 until 2013, Russia would participate in every G7/8 Summit. This strategy of ever-closer incorporation of Russia into their club seemed to work for the first decade (from 1989-1999), as Gorbachev and Yeltsin clearly sought integration with western institutions, such as the IMF, the World Bank, the EU, and NATO.

In constructing the G8, the G7 overlooked a number of Russia’s shortcomings in order to reward Moscow’s enthusiasm. In particular, President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair decided that G8 membership for Russia was needed to soften the blow of NATO’s 1997 expansion, acknowledge Yeltsin’s progress on democratic reforms, and reward his willingness to give up territorial claims on former Soviet states.

1999: End of the Millennium and the Honeymoon

Russia was invited to participate at the level of head of state at the Summit of Eight in Denver in 1997–though not as a full member, as the G7 released a separate communiqué on economic matters. The first meeting of the G8 did not take place until 1998 in Birmingham, and the first cracks appeared soon thereafter.

When NATO intervened in Kosovo in1999, the G8 declared its approval of draft UN Security Council Resolution language. Yet Russia clearly was not pleased, as Russian Foreign Minister noted during the press conference, “…there's no point in saying what I am more or less satisfied with.”

Meanwhile, many Russians were disillusioned with western institutions due to persistent economic hardship and their perpetually intoxicated pro-western President, Boris Yeltsin. Russia was ready for a new direction, and on New Year’s Eve in 1999, it got one when Yeltsin turned his presidency over to his young Prime Minister: Vladimir Putin.

At first, the G7 welcomed Putin’s ability to restore order and economic growth. However, it became clear that Putin–despite being economically liberal–did not share Yeltsin’s desire to import democratic values. Instead, he underscored the need for stability, security, and a role for Russia commensurate with its historical status as a great power.

The Emperor’s New Institutions

Despite the ideological rift–both politically, as the Kremlin consolidated political power in a single-party system, and economically, as efforts for diversifying Russia’s economy fizzled–the G7 nations continued to institutionalize Russia’s role in the G8, perhaps hoping that in so doing they could cement Russia into the liberal democratic world order. Thus, the G7 nations agreed to let Russia host its first G8 summit in 2006.

But the deepening discord kept bubbling up to the surface. In 2004, disagreement over U.S. involvement in Iraq and Russian interference in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution led to tense exchanges between the United States and Russia at the Georgia Island summit. The list of mutual grievances grew to include western objections to Russia’s use of natural gas as a political tool and Russian objections to U.S. ballistic missile defense. Relations hit a low point during the 2008 Russia-Georgia War.

Concurrent with deteriorating relations with the west, Russia was carving a niche for itself outside the Washington consensus. In 2009, Russia hailed the creation of the G20 as a more appropriate forum for deciding global economic issues. The Kremlin deemed this forum, as well as the BRICS summits of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, more in keeping with Russia’s new vision of itself as a key ‘pole’ in an increasingly multipolar world.

The End of the Affair

The Obama Administration’s effort to improve U.S.-Russian relations did not last long. Russian opposition to U.S. intervention in Libya, deteriorating human rights in Russia, Russian sheltering of whistleblower Edward Snowden and opposition to intervention in Syria culminated in the dual snubs of President Vladimir Putin boycotting the 2012 G8 summit in Camp David, followed by President Obama cancelling a planned bilateral meeting on the margins of the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg. Finally, in 2014, the G8 project–which had been limping along for years–collapsed under the weight of the war in Ukraine.

Future: Tense

The change in Russia’s policy introduced during Putin’s first presidency knocked Russia from the path of integration in the western world order. Though the heads of the G8 spent over a decade putting on brave faces and issuing rosy communiqués, the war in Ukraine has finally laid these differences bare.

With Russia out for now, the G7 may struggle to maintain its role as a pre-eminent voice on political and economic policy in the world. It should respond by ceasing to pretend that it is an inclusive forum for dialogue.

The G7 was founded as a group of like-minded, industrialized liberal democracies whose ability to come together to make policy on a range of issues – from fiscal and monetary adjustments and energy security to counter-terrorism – is better served when its members are like-minded states and not, as in the G8, a group of seven like-minded states and one spoiler.

Going forward, the G7 should focus its mission on providing a positive alternative to the rising tide of state capitalism and increasing authoritarianism. In short, it needs to become the club that a more democratic Russia – down the road – may want to join again.

Ann Dailey is an expert on the Eurasian region with experience in defense and energy. She has a Master's degree in International Economics from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a Bachelor's degree in Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian Affairs from the University of Illinois.

Since G7 cooperation with Moscow began in 1989, the average G7 GDP per capita has been more than five times that of Russia’s, and even at its most open and democratic, Russia was never on the same plane as the rest of the G7 in terms of democratic governance and freedom.

However, the G7 nations used cooperation as a carrot to coax Russia ever more firmly into their club. At the ‘Summit of the Arch’ in France in 1989, Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev wrote to French President Mitterand on the importance of finding a ‘methodology’ for mutually beneficial macroeconomic coordination. In his post-Summit press conference, Mitterand did not exclude the possibility of the Soviet Union joining the G7.

Two years later, the Soviet Union participated in the 1991 London Summit, and from 1992 until 2013, Russia would participate in every G7/8 Summit. This strategy of ever-closer incorporation of Russia into their club seemed to work for the first decade (from 1989-1999), as Gorbachev and Yeltsin clearly sought integration with western institutions, such as the IMF, the World Bank, the EU, and NATO.

In constructing the G8, the G7 overlooked a number of Russia’s shortcomings in order to reward Moscow’s enthusiasm. In particular, President Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair decided that G8 membership for Russia was needed to soften the blow of NATO’s 1997 expansion, acknowledge Yeltsin’s progress on democratic reforms, and reward his willingness to give up territorial claims on former Soviet states.

1999: End of the Millennium and the Honeymoon

Russia was invited to participate at the level of head of state at the Summit of Eight in Denver in 1997–though not as a full member, as the G7 released a separate communiqué on economic matters. The first meeting of the G8 did not take place until 1998 in Birmingham, and the first cracks appeared soon thereafter.

When NATO intervened in Kosovo in1999, the G8 declared its approval of draft UN Security Council Resolution language. Yet Russia clearly was not pleased, as Russian Foreign Minister noted during the press conference, “…there's no point in saying what I am more or less satisfied with.”

Meanwhile, many Russians were disillusioned with western institutions due to persistent economic hardship and their perpetually intoxicated pro-western President, Boris Yeltsin. Russia was ready for a new direction, and on New Year’s Eve in 1999, it got one when Yeltsin turned his presidency over to his young Prime Minister: Vladimir Putin.

At first, the G7 welcomed Putin’s ability to restore order and economic growth. However, it became clear that Putin–despite being economically liberal–did not share Yeltsin’s desire to import democratic values. Instead, he underscored the need for stability, security, and a role for Russia commensurate with its historical status as a great power.

The Emperor’s New Institutions

Despite the ideological rift–both politically, as the Kremlin consolidated political power in a single-party system, and economically, as efforts for diversifying Russia’s economy fizzled–the G7 nations continued to institutionalize Russia’s role in the G8, perhaps hoping that in so doing they could cement Russia into the liberal democratic world order. Thus, the G7 nations agreed to let Russia host its first G8 summit in 2006.

But the deepening discord kept bubbling up to the surface. In 2004, disagreement over U.S. involvement in Iraq and Russian interference in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution led to tense exchanges between the United States and Russia at the Georgia Island summit. The list of mutual grievances grew to include western objections to Russia’s use of natural gas as a political tool and Russian objections to U.S. ballistic missile defense. Relations hit a low point during the 2008 Russia-Georgia War.

Concurrent with deteriorating relations with the west, Russia was carving a niche for itself outside the Washington consensus. In 2009, Russia hailed the creation of the G20 as a more appropriate forum for deciding global economic issues. The Kremlin deemed this forum, as well as the BRICS summits of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, more in keeping with Russia’s new vision of itself as a key ‘pole’ in an increasingly multipolar world.

The End of the Affair

The Obama Administration’s effort to improve U.S.-Russian relations did not last long. Russian opposition to U.S. intervention in Libya, deteriorating human rights in Russia, Russian sheltering of whistleblower Edward Snowden and opposition to intervention in Syria culminated in the dual snubs of President Vladimir Putin boycotting the 2012 G8 summit in Camp David, followed by President Obama cancelling a planned bilateral meeting on the margins of the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg. Finally, in 2014, the G8 project–which had been limping along for years–collapsed under the weight of the war in Ukraine.

Future: Tense

The change in Russia’s policy introduced during Putin’s first presidency knocked Russia from the path of integration in the western world order. Though the heads of the G8 spent over a decade putting on brave faces and issuing rosy communiqués, the war in Ukraine has finally laid these differences bare.

With Russia out for now, the G7 may struggle to maintain its role as a pre-eminent voice on political and economic policy in the world. It should respond by ceasing to pretend that it is an inclusive forum for dialogue.

The G7 was founded as a group of like-minded, industrialized liberal democracies whose ability to come together to make policy on a range of issues – from fiscal and monetary adjustments and energy security to counter-terrorism – is better served when its members are like-minded states and not, as in the G8, a group of seven like-minded states and one spoiler.

Going forward, the G7 should focus its mission on providing a positive alternative to the rising tide of state capitalism and increasing authoritarianism. In short, it needs to become the club that a more democratic Russia – down the road – may want to join again.

Ann Dailey is an expert on the Eurasian region with experience in defense and energy. She has a Master's degree in International Economics from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a Bachelor's degree in Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian Affairs from the University of Illinois.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.