.

Innovation is a powerful driver in the world of business, and companies recognized as highly innovative are hailed as leaders in their fields, with a share value reflecting the public’s confidence in their leadership. We have followed rapid change in sectors where old, but by no means stagnant, corporations like Ford Motor Co. has yielded leadership to highly innovative companies like Tesla Motors. Creative internet retailers like Amazon are taking huge market shares from brick and mortar retailers like K-Mart forcing them to change their marketing and sales strategies.

Accurate assessment of innovation potential in the corporate world is not trivial. However, Jeff Dyer (Brigham Young University) and Hal Gregersen (MIT) developed a paradigm using an objectively calculated “Innovation Premium,” based on which they published a list of the world’s ten most innovative companies in Forbes (2017, 1). This list includes Chinese, Indonesian and South Korean corporations, but it is dominated by US names, such as Salesforce, Tesla, Amazon (1, 2 and 3, respectively), Netflix, Incyte and Regeneron (5, 6 and 10, respectively). Not surprisingly, these companies also rank as top leaders in the 2017 list of Future Fortune 50 corporations.

Important as it may be to shareholders and employees, corporate innovation prowess is most interesting if it contributes to the greater good of humankind, worldwide.

In a global comparison, the Global Innovation Index (2), released annually by Cornell’s SC Johnson College of Business, INSEAD and World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) ranks 127 countries based on a number of contributing factors. Now on its tenth year, the GII has dedicated the 2017 report to the topic of Innovation Feeding the World in recognition of the vital role of innovation to address one of the world’s most challenging sustainability issues. It also highlights the power of governmental responsibility to stimulate innovation and R&D through investment and taxation. Food production and agriculture are among the oldest pillars of national wellbeing, now more dependent on innovation, digitization and efficiency increase than ever before. It is rewarding to know that this is happening at a rapid pace.

The GII rank list, topped by Switzerland, Sweden and the Netherlands, shows predominantly highly sophisticated economies in its upper half, and mostly poor, developing countries in the lower half, ending with Togo, Guinea and Yemen. This implies that, if innovation is a prime weapon in defeating world hunger, it will be necessary not only to distribute food to those who need it most, but also to transfer innovation skills to these nations.

We are now approaching the crux of the matter. How can creativity and innovation skills be bottled and shipped to the needy?

Better yet, how can we help inspire educators (and policy makers) across the globe to stimulate and nourish the development of creativity and innovation skills from an early age?

Creativity vs. Innovation. Is there a difference?

Andrew Marshall (3) states that “The main difference between creativity and innovation is the focus. Creativity is about unleashing the potential of the mind to conceive new ideas… It is also subjective, making it hard to measure…” whereas “Innovation, on the other hand, is completely measurable. Innovation is about introducing change into relatively stable systems. It’s also concerned with the work required to make an idea viable. “

As an applied business example, a pharmaceutical company may recognize an unmet medical need and invest in innovative R&D to develop a medicine which is projected to bring a fiscal return on the investment many years and billions of dollars later. What about creativity in this context? Theodore Levitt, the late Harvard economist who coined the term “Globalization” might have clarified the relationship: “What is often lacking is not creativity in the idea-creating sense but innovation in the action-producing sense, i.e. putting ideas to work.”

If Creativity leads to Ideation, and Innovation best relates to Implementation, then both skills are necessary and intimately connected. It makes sense then, to encourage young learners to practice both skills together.

Among educators who take special interest in the STEM field of education, it is well-known that by exercising practical problem solving, learners are stimulated to think creatively. Farming advocates are likely to be correct when they assert “Challenges often arise on a farm; addressing these issues develops skill in independent thinking, problem solving, ingenuity, and offering creative, innovative solutions.” (4).

Can creativity be taught?

While the question is interesting, any straight-forward answer is likely to be met with skepticism, largely because no clear evidence exists for or against.

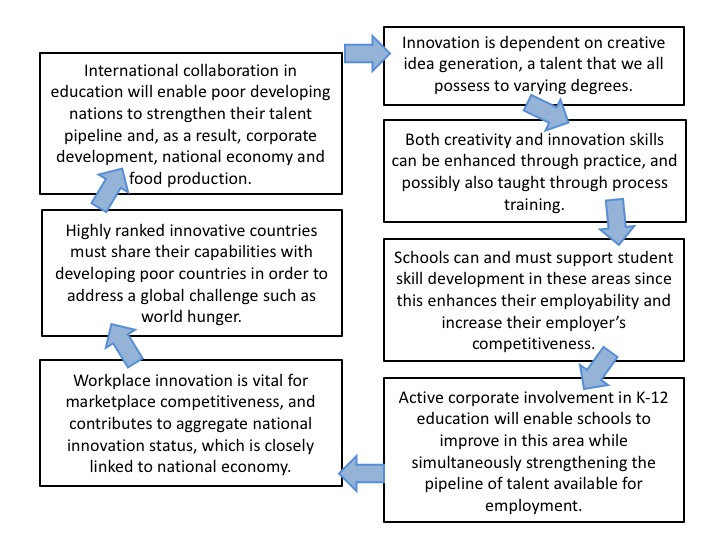

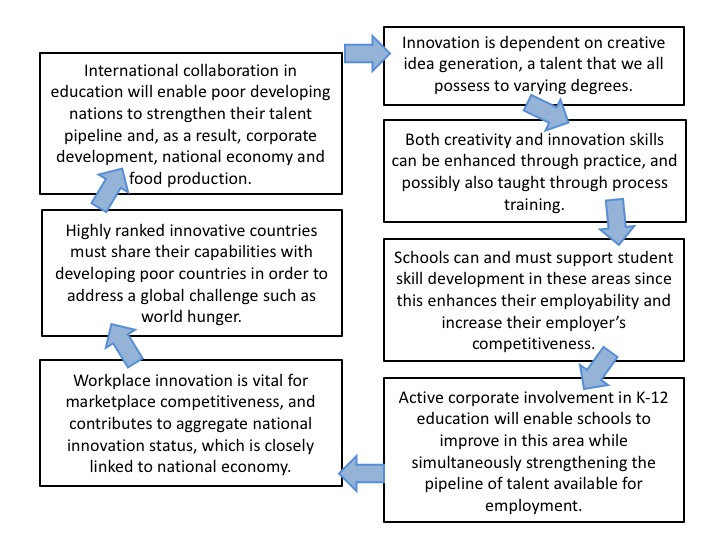

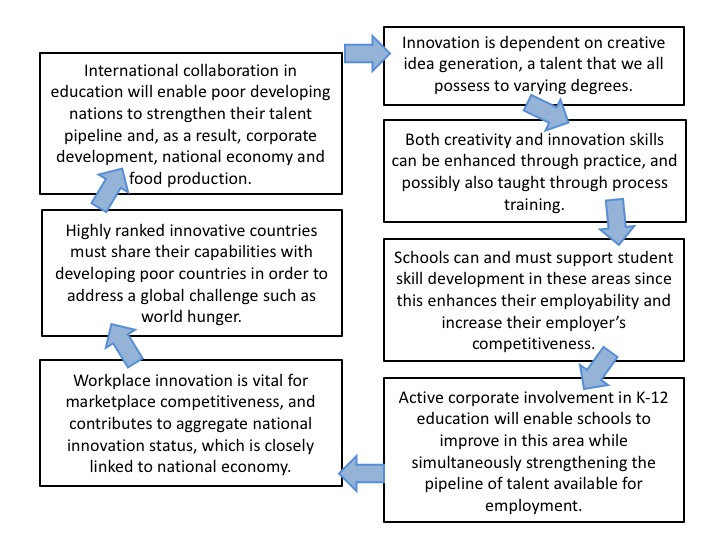

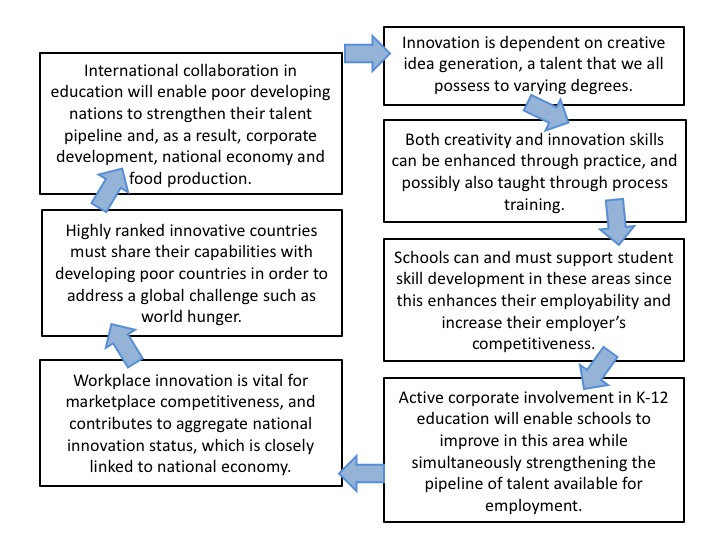

First, let us consider creativity as the initial step of developing a novel idea. Jeff DeGraff (5) suggests that “Everyone is creative, but in very different ways and to varying degree.” We all have creative talent, but very few of us come close to Archimedes or Ludwig van Beethoven.

It is frequently said among STEM educators that every child is naturally and fearlessly curious and explorative, and our job is to encourage and nurture these talents. Ideally, Hippocrates’ Oath “Do No Harm” should also apply to the education establishment, since some education practices can, in fact, have the opposite effect on the learner, namely to squelch and dampen curiosity and the joy of learning.

DeGraff goes on to define five types and levels of creativity (6):

Again, teachers are at the focus of intervention.

It Is not helpful to educators to have increasing demands on their time and performance. Instead, they should be encouraged to review existing materials and lesson plans for opportunities to insert creativity and innovation exercises in their daily student interaction. Curriculum materials specifically designed to stimulate inquiry (STC, FOSS, Insights) are uniquely suitable for such activities. In-service teacher professional development dedicated to the use of these curriculum materials offer unique opportunities to explore the teacher’s role in this important endeavor. As always, the teacher is the Master of the Classroom, and any and all activities offered to assist in his/her work must be adapted to the situation at hand.

Again, teachers are at the focus of intervention.

It Is not helpful to educators to have increasing demands on their time and performance. Instead, they should be encouraged to review existing materials and lesson plans for opportunities to insert creativity and innovation exercises in their daily student interaction. Curriculum materials specifically designed to stimulate inquiry (STC, FOSS, Insights) are uniquely suitable for such activities. In-service teacher professional development dedicated to the use of these curriculum materials offer unique opportunities to explore the teacher’s role in this important endeavor. As always, the teacher is the Master of the Classroom, and any and all activities offered to assist in his/her work must be adapted to the situation at hand.

- Mimetic Creativity. This is the most basic form of creativity, which uses mimicry of a behavior to solve a problem in another application area.

- Bisociative Creativity. Arthur Koestler introduced the term “Bisociation” (7)to describe how our conscious mind can combine rational and intuitive thoughts to produce Eureka

- Fluency – It is more productive to have lots of unpolished ideas than a few “good” ones because the greater the diversity of ideas, the wider the range of possible solutions

- Flexibility– The “right” ideas put it in the “wrong” places fails to solve the problem so we have to move them around to see where they best fit to meet our challenges

- Flow– It is near-impossible to be creative on demand, as an author suffering from writer’s block can attest to. We need to be both simulated and relaxed to draw out the energy required to create. Ideas pop while in the shower, listening to music or even sleeping.

- Analogical Creativity. We use analogies to transfer information that we believe we understand in one domain (the source) to help resolve a challenge in an unfamiliar area (the target). For example, vacuum cleaner design was largely unchanged for nearly a century when inventor James Dyson used a different analogue — cyclones — to separate particles through the spinning force of a centrifuge.

- Narrative Creativity. Narrative is a story communicated in sequence. It is how the tale is told. Stories can be readily deconstructed and reconstructed to make different version – as we recognize when trying to re-tell a good joke.

- Intuitive Creativity. This is the synthesis of novel ideas at its most complex level. Sophy Burnham (The Art of Intuition, 2011, 8) defines intuition: “… as the subtle knowing without ever having any idea why you know it.” “It’s different from thinking, it’s different from logic or analysis ... It’s a knowing without knowing.”

- Equate innovation to other skills-based activities. Innovating takes skill just like sports or dancing. Don't let children think innovation is some special, innate talent that only certain kids have.

- De-emphasize patents. Patents are often seen as the ultimate reward of innovation. If a child invents something that has already been invented, this is a success, since it shows an ability to create novel ideas that have a track record of success.

- Apply innovation across a variety of situations. It is not just for inventing new products. Teach children to apply innovation methods to things like writing a poem, doing school work or getting dressed in the morning. Make innovation a routine way to tackle new situations.

- Distinguish between innovation skills and problem-solving skills. They are related, but different skills. Example: Innovate a new way to clean their room, but problem-solve when they want to avoid having to do it.

- Teach "ambidextrous" innovation. There are two directions of innovation: Problem-to-Solution and Solution-to-Problem. Example: If the kitchen toaster keeps burning the bread, a novel way to fix it is Problem-to-Solution. Other the other hand, if a toaster is programmed to work “on-demand” then the toast can be ready precisely when you want it. This is Solution-to-Problem innovation.

- Set an example. Parents and teachers must "walk the talk." Innovation is no different. Let children see how you and others, especially other children, use innovation methods to do cool, fun, and important things.

- Explaining non-formal learning to employers and educators

- Translating non-formal learning outcomes to the world of work

- Enhancing the ability of those working directly with young people

- Developing a strong focus on entrepreneurship

- Improving partnership working and cross-sector innovation

- Extending the evidence base through focused research and impact analysis

- Including non-formal education and learning in Youth Guarantee* plans

Again, teachers are at the focus of intervention.

It Is not helpful to educators to have increasing demands on their time and performance. Instead, they should be encouraged to review existing materials and lesson plans for opportunities to insert creativity and innovation exercises in their daily student interaction. Curriculum materials specifically designed to stimulate inquiry (STC, FOSS, Insights) are uniquely suitable for such activities. In-service teacher professional development dedicated to the use of these curriculum materials offer unique opportunities to explore the teacher’s role in this important endeavor. As always, the teacher is the Master of the Classroom, and any and all activities offered to assist in his/her work must be adapted to the situation at hand.

Again, teachers are at the focus of intervention.

It Is not helpful to educators to have increasing demands on their time and performance. Instead, they should be encouraged to review existing materials and lesson plans for opportunities to insert creativity and innovation exercises in their daily student interaction. Curriculum materials specifically designed to stimulate inquiry (STC, FOSS, Insights) are uniquely suitable for such activities. In-service teacher professional development dedicated to the use of these curriculum materials offer unique opportunities to explore the teacher’s role in this important endeavor. As always, the teacher is the Master of the Classroom, and any and all activities offered to assist in his/her work must be adapted to the situation at hand.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.

a global affairs media network

Teaching Students to Defeat World Hunger Through Creativity and Innovation

Little girl plays astronaut. Child on the background of sunset sky. Kid is looking at falling star and dreaming of becoming a spaceman.|

January 16, 2018

Innovation is a powerful driver in the world of business, and companies recognized as highly innovative are hailed as leaders in their fields, with a share value reflecting the public’s confidence in their leadership. We have followed rapid change in sectors where old, but by no means stagnant, corporations like Ford Motor Co. has yielded leadership to highly innovative companies like Tesla Motors. Creative internet retailers like Amazon are taking huge market shares from brick and mortar retailers like K-Mart forcing them to change their marketing and sales strategies.

Accurate assessment of innovation potential in the corporate world is not trivial. However, Jeff Dyer (Brigham Young University) and Hal Gregersen (MIT) developed a paradigm using an objectively calculated “Innovation Premium,” based on which they published a list of the world’s ten most innovative companies in Forbes (2017, 1). This list includes Chinese, Indonesian and South Korean corporations, but it is dominated by US names, such as Salesforce, Tesla, Amazon (1, 2 and 3, respectively), Netflix, Incyte and Regeneron (5, 6 and 10, respectively). Not surprisingly, these companies also rank as top leaders in the 2017 list of Future Fortune 50 corporations.

Important as it may be to shareholders and employees, corporate innovation prowess is most interesting if it contributes to the greater good of humankind, worldwide.

In a global comparison, the Global Innovation Index (2), released annually by Cornell’s SC Johnson College of Business, INSEAD and World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) ranks 127 countries based on a number of contributing factors. Now on its tenth year, the GII has dedicated the 2017 report to the topic of Innovation Feeding the World in recognition of the vital role of innovation to address one of the world’s most challenging sustainability issues. It also highlights the power of governmental responsibility to stimulate innovation and R&D through investment and taxation. Food production and agriculture are among the oldest pillars of national wellbeing, now more dependent on innovation, digitization and efficiency increase than ever before. It is rewarding to know that this is happening at a rapid pace.

The GII rank list, topped by Switzerland, Sweden and the Netherlands, shows predominantly highly sophisticated economies in its upper half, and mostly poor, developing countries in the lower half, ending with Togo, Guinea and Yemen. This implies that, if innovation is a prime weapon in defeating world hunger, it will be necessary not only to distribute food to those who need it most, but also to transfer innovation skills to these nations.

We are now approaching the crux of the matter. How can creativity and innovation skills be bottled and shipped to the needy?

Better yet, how can we help inspire educators (and policy makers) across the globe to stimulate and nourish the development of creativity and innovation skills from an early age?

Creativity vs. Innovation. Is there a difference?

Andrew Marshall (3) states that “The main difference between creativity and innovation is the focus. Creativity is about unleashing the potential of the mind to conceive new ideas… It is also subjective, making it hard to measure…” whereas “Innovation, on the other hand, is completely measurable. Innovation is about introducing change into relatively stable systems. It’s also concerned with the work required to make an idea viable. “

As an applied business example, a pharmaceutical company may recognize an unmet medical need and invest in innovative R&D to develop a medicine which is projected to bring a fiscal return on the investment many years and billions of dollars later. What about creativity in this context? Theodore Levitt, the late Harvard economist who coined the term “Globalization” might have clarified the relationship: “What is often lacking is not creativity in the idea-creating sense but innovation in the action-producing sense, i.e. putting ideas to work.”

If Creativity leads to Ideation, and Innovation best relates to Implementation, then both skills are necessary and intimately connected. It makes sense then, to encourage young learners to practice both skills together.

Among educators who take special interest in the STEM field of education, it is well-known that by exercising practical problem solving, learners are stimulated to think creatively. Farming advocates are likely to be correct when they assert “Challenges often arise on a farm; addressing these issues develops skill in independent thinking, problem solving, ingenuity, and offering creative, innovative solutions.” (4).

Can creativity be taught?

While the question is interesting, any straight-forward answer is likely to be met with skepticism, largely because no clear evidence exists for or against.

First, let us consider creativity as the initial step of developing a novel idea. Jeff DeGraff (5) suggests that “Everyone is creative, but in very different ways and to varying degree.” We all have creative talent, but very few of us come close to Archimedes or Ludwig van Beethoven.

It is frequently said among STEM educators that every child is naturally and fearlessly curious and explorative, and our job is to encourage and nurture these talents. Ideally, Hippocrates’ Oath “Do No Harm” should also apply to the education establishment, since some education practices can, in fact, have the opposite effect on the learner, namely to squelch and dampen curiosity and the joy of learning.

DeGraff goes on to define five types and levels of creativity (6):

Again, teachers are at the focus of intervention.

It Is not helpful to educators to have increasing demands on their time and performance. Instead, they should be encouraged to review existing materials and lesson plans for opportunities to insert creativity and innovation exercises in their daily student interaction. Curriculum materials specifically designed to stimulate inquiry (STC, FOSS, Insights) are uniquely suitable for such activities. In-service teacher professional development dedicated to the use of these curriculum materials offer unique opportunities to explore the teacher’s role in this important endeavor. As always, the teacher is the Master of the Classroom, and any and all activities offered to assist in his/her work must be adapted to the situation at hand.

Again, teachers are at the focus of intervention.

It Is not helpful to educators to have increasing demands on their time and performance. Instead, they should be encouraged to review existing materials and lesson plans for opportunities to insert creativity and innovation exercises in their daily student interaction. Curriculum materials specifically designed to stimulate inquiry (STC, FOSS, Insights) are uniquely suitable for such activities. In-service teacher professional development dedicated to the use of these curriculum materials offer unique opportunities to explore the teacher’s role in this important endeavor. As always, the teacher is the Master of the Classroom, and any and all activities offered to assist in his/her work must be adapted to the situation at hand.

- Mimetic Creativity. This is the most basic form of creativity, which uses mimicry of a behavior to solve a problem in another application area.

- Bisociative Creativity. Arthur Koestler introduced the term “Bisociation” (7)to describe how our conscious mind can combine rational and intuitive thoughts to produce Eureka

- Fluency – It is more productive to have lots of unpolished ideas than a few “good” ones because the greater the diversity of ideas, the wider the range of possible solutions

- Flexibility– The “right” ideas put it in the “wrong” places fails to solve the problem so we have to move them around to see where they best fit to meet our challenges

- Flow– It is near-impossible to be creative on demand, as an author suffering from writer’s block can attest to. We need to be both simulated and relaxed to draw out the energy required to create. Ideas pop while in the shower, listening to music or even sleeping.

- Analogical Creativity. We use analogies to transfer information that we believe we understand in one domain (the source) to help resolve a challenge in an unfamiliar area (the target). For example, vacuum cleaner design was largely unchanged for nearly a century when inventor James Dyson used a different analogue — cyclones — to separate particles through the spinning force of a centrifuge.

- Narrative Creativity. Narrative is a story communicated in sequence. It is how the tale is told. Stories can be readily deconstructed and reconstructed to make different version – as we recognize when trying to re-tell a good joke.

- Intuitive Creativity. This is the synthesis of novel ideas at its most complex level. Sophy Burnham (The Art of Intuition, 2011, 8) defines intuition: “… as the subtle knowing without ever having any idea why you know it.” “It’s different from thinking, it’s different from logic or analysis ... It’s a knowing without knowing.”

- Equate innovation to other skills-based activities. Innovating takes skill just like sports or dancing. Don't let children think innovation is some special, innate talent that only certain kids have.

- De-emphasize patents. Patents are often seen as the ultimate reward of innovation. If a child invents something that has already been invented, this is a success, since it shows an ability to create novel ideas that have a track record of success.

- Apply innovation across a variety of situations. It is not just for inventing new products. Teach children to apply innovation methods to things like writing a poem, doing school work or getting dressed in the morning. Make innovation a routine way to tackle new situations.

- Distinguish between innovation skills and problem-solving skills. They are related, but different skills. Example: Innovate a new way to clean their room, but problem-solve when they want to avoid having to do it.

- Teach "ambidextrous" innovation. There are two directions of innovation: Problem-to-Solution and Solution-to-Problem. Example: If the kitchen toaster keeps burning the bread, a novel way to fix it is Problem-to-Solution. Other the other hand, if a toaster is programmed to work “on-demand” then the toast can be ready precisely when you want it. This is Solution-to-Problem innovation.

- Set an example. Parents and teachers must "walk the talk." Innovation is no different. Let children see how you and others, especially other children, use innovation methods to do cool, fun, and important things.

- Explaining non-formal learning to employers and educators

- Translating non-formal learning outcomes to the world of work

- Enhancing the ability of those working directly with young people

- Developing a strong focus on entrepreneurship

- Improving partnership working and cross-sector innovation

- Extending the evidence base through focused research and impact analysis

- Including non-formal education and learning in Youth Guarantee* plans

Again, teachers are at the focus of intervention.

It Is not helpful to educators to have increasing demands on their time and performance. Instead, they should be encouraged to review existing materials and lesson plans for opportunities to insert creativity and innovation exercises in their daily student interaction. Curriculum materials specifically designed to stimulate inquiry (STC, FOSS, Insights) are uniquely suitable for such activities. In-service teacher professional development dedicated to the use of these curriculum materials offer unique opportunities to explore the teacher’s role in this important endeavor. As always, the teacher is the Master of the Classroom, and any and all activities offered to assist in his/her work must be adapted to the situation at hand.

Again, teachers are at the focus of intervention.

It Is not helpful to educators to have increasing demands on their time and performance. Instead, they should be encouraged to review existing materials and lesson plans for opportunities to insert creativity and innovation exercises in their daily student interaction. Curriculum materials specifically designed to stimulate inquiry (STC, FOSS, Insights) are uniquely suitable for such activities. In-service teacher professional development dedicated to the use of these curriculum materials offer unique opportunities to explore the teacher’s role in this important endeavor. As always, the teacher is the Master of the Classroom, and any and all activities offered to assist in his/her work must be adapted to the situation at hand.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.