Pundits, politicians, and professors have debated the merits of continued military aid to Egypt. Much of this discussion centers on whether the violent removal of President Mohamed Morsi was a coup and whether continued aid is therefore illegal under U.S law. Although public opinion polls show that 51 percent of respondents support cutting off aid, to date, no systematic effort has been made to gauge the opinions of scholars who study international relations (IR) for a living.

The Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) Project at the College of William & Mary works to bridge the gap between scholars and the policy community. This spring, for the first time, TRIP conducted two Snap Polls of scholars in the United States about contemporary international events.

The May 2014 Snap Poll included questions on military aid to Egypt. Results show that a large majority, almost 60 percent of IR scholars believe that military aid to Egypt should be decreased or stopped altogether, while 34 percent of experts think aid should be increased or kept about the same. Few scholars support cutting aid altogether.

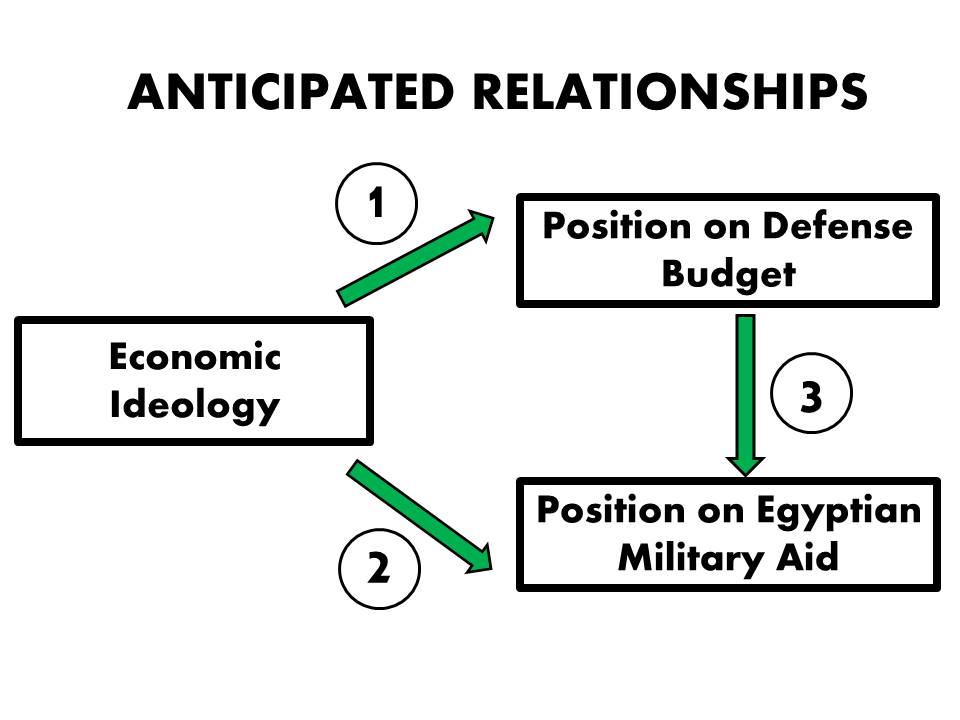

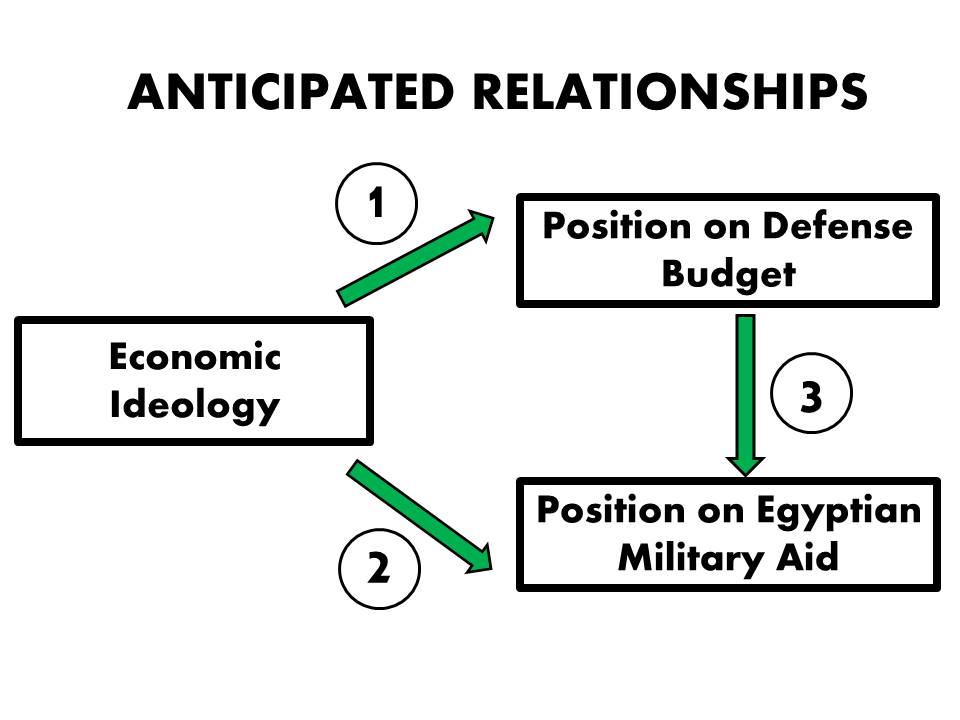

In an era of fiscal austerity, debate often centers on prioritization of spending. In the United States, conservatives tend to support cutting social programs to ensure continued defense spending, while liberals tend to place more emphasis on funding social programs, at the expense of the defense budget. With these general trends in mind, I anticipated that scholars who identify as liberal on economic issues would be more likely than those who identify as conservative to say that the United States is spending too much on defense (#1 below) and to support decreasing military aid to Egypt (#2). I also expected that those in favor of a smaller defense budget would be opposed to increasing aid to Egypt, and more likely to support decreasing aid (#3).

What do we observe? First, as predicted, a scholar’s economic ideology is correlated with his or her position on defense spending. In our March Snap Poll, we asked about defense spending; 44 percent of conservative IR scholars and 81 percent of liberal IR scholars said that it is too high. At first glance, these findings could suggest that the ideological divide is alive and well in the academy. On closer inspection, however, a different conclusion emerges.

TRIP data show that the vast majority of economically liberal IR scholars support reduced defense spending, but they also show that the gap between economically liberal and economically conservative IR scholars is less dramatic on this issue than one might expect given conventional wisdom. A plurality of conservative IR scholars (44 percent) believes that defense spending is too high, suggesting that there may be more common ground within the academy on the topic of defense spending than conventional wisdom suggests.

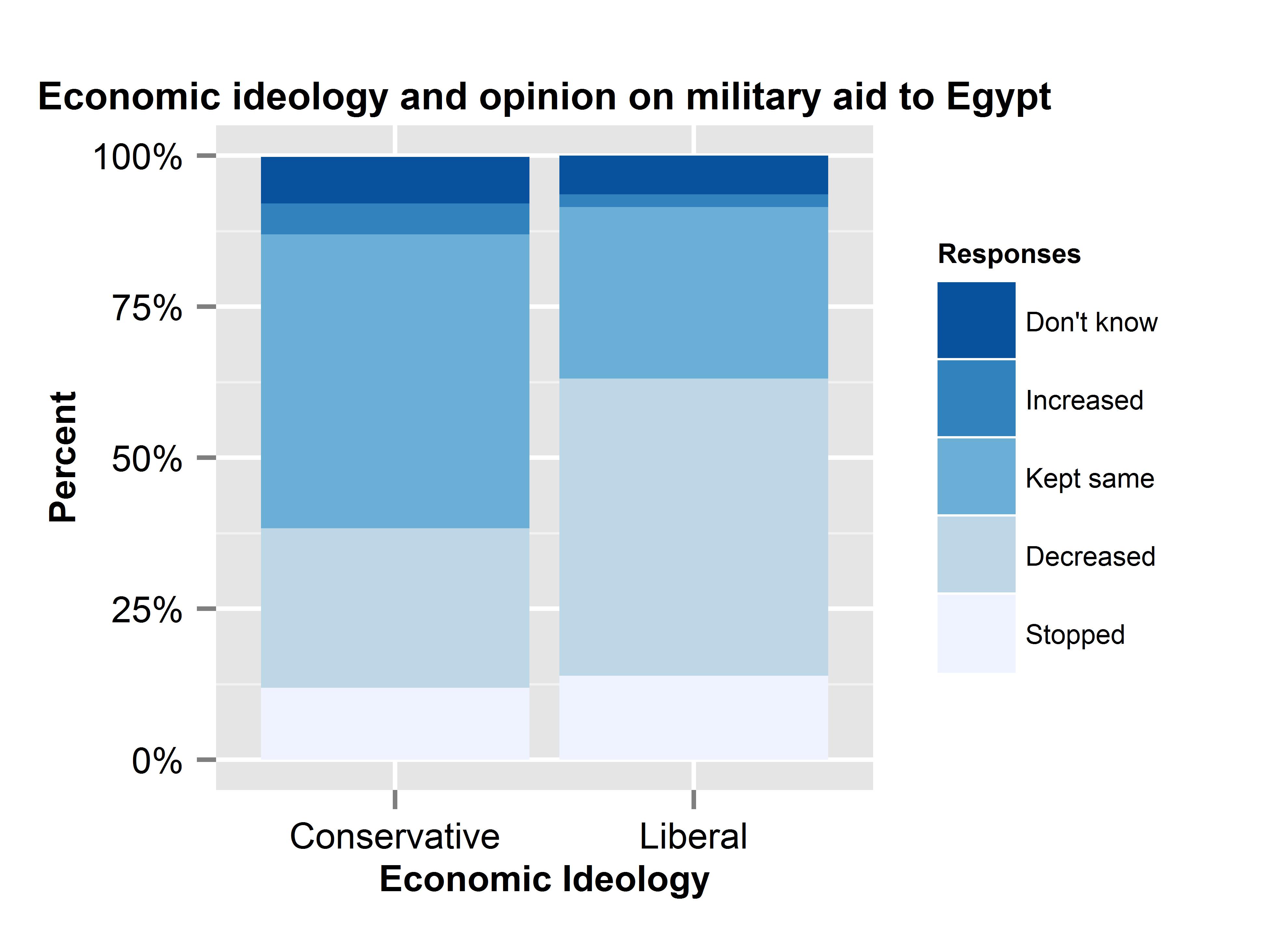

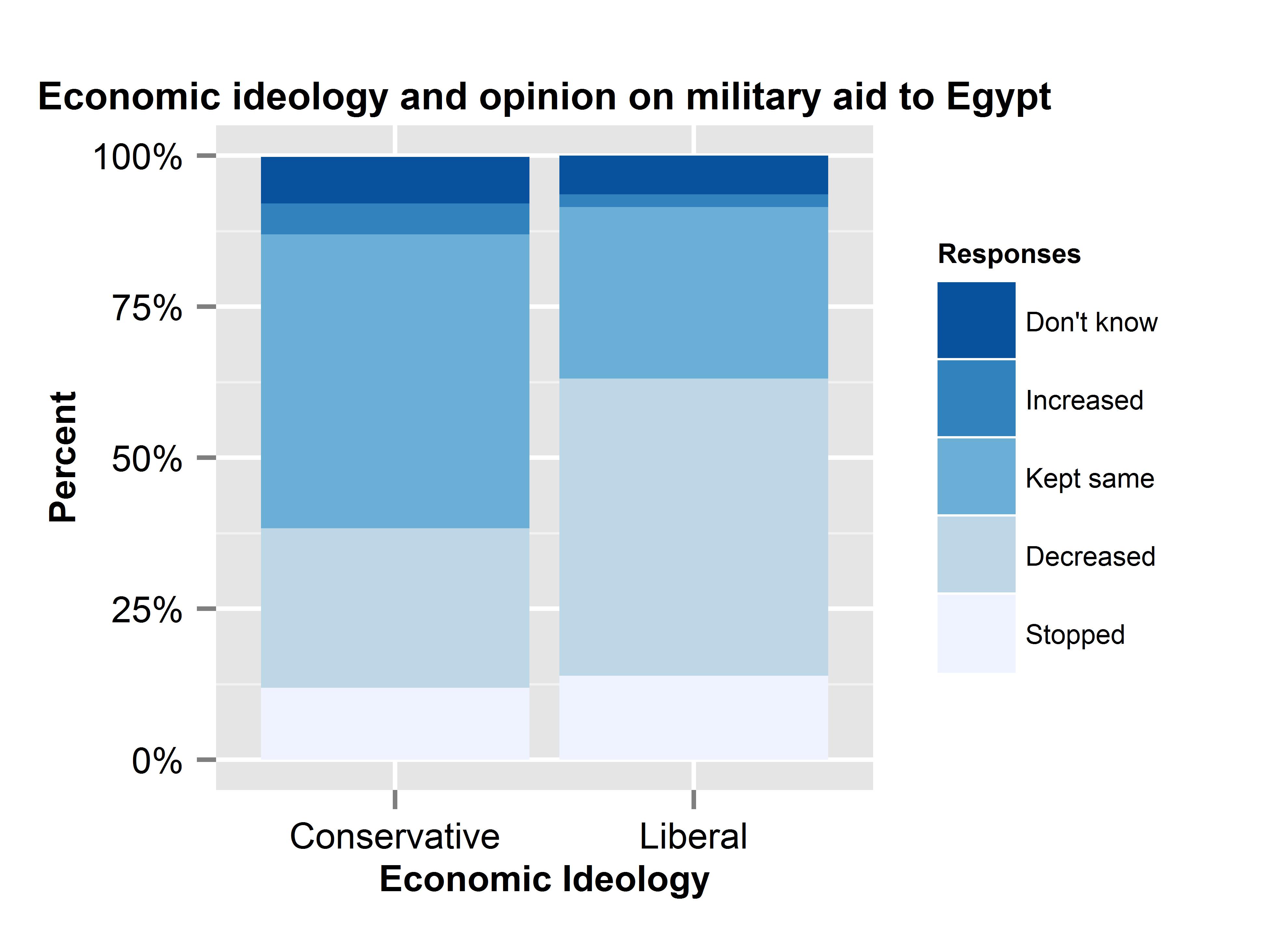

Second, economic ideology correlates with views on Egyptian military aid. Approximately one in four self-proclaimed conservatives say military aid to Egypt should be decreased, while about half of liberals agree. At the same time, similar percentages of conservative and liberal IR scholars tend to believe that we should stop aid altogether (twelve and fourteen percent, respectively), or increase aid (five and two percent, respectively). Over 75 percent of both liberal and conservative IR scholars believe that aid to Egypt should be either kept about the same or decreased. Again, the ideological divide seems smaller than suggested by the conventional wisdom.

We see a similar pattern among policymakers in Washington. Although the debate in Congress over aid in Egypt started as a fairly partisan issue, the debate today is defined less by partisanship than it was in the past. Senator McCain has toned down his rhetoric, and Senator Leahy has become more outspoken about the need for continued military aid. Party affiliation is no longer a clear predictor of a politician’s stance on military aid to Egypt.

Finally, IR scholars’ views on the defense budget are not correlated with their positions on Egyptian military aid. Those who think that the United States is spending too much on defense are not statistically more likely than those who think that defense spending is too low or about right to have a particular position on military aid to Egypt.

The absence of a relationship between IR scholars’ responses to questions on the defense budget and on Egyptian military aid suggests that these experts do not think of military aid to Egypt primarily as a budgetary issue; perhaps they view it more as a geo-political issue, divorced from funding concerns. Such a viewpoint would be logical: $1.5 billion sounds like a sizable sum of money, but Egyptian military aid is only about three percent of the foreign aid budget, which itself accounts for just over one percent of the federal budget.

Defense spending and continued provision of military aid are traditionally portrayed as ideologically divisive issues, but IR experts’ views on these issues are less likely to break down along ideological lines than are the opinions of the rest of the American public. Scholars appear to be less ideologically driven, perhaps because they share a knowledge base and educational background that allows them to overcome ideological differences. Further research on the extent to which ideology and party affiliation affect individual views will help us better understand how scholarly opinion can influence policy, as well as how to overcome ideological divides within Congress and the general public on defense spending, military aid, and other foreign policy issues.

Rachel Merriman-Goldring is a Research Assistant at the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) project and an undergraduate student at the College of William & Mary. She can be reached at remerrimangold@email.wm.edu.

Photo: Sebastian Horndasch (cc).

a global affairs media network

On U.S. Aid to Egypt, Is There an Ideological Divide?

June 12, 2014

Pundits, politicians, and professors have debated the merits of continued military aid to Egypt. Much of this discussion centers on whether the violent removal of President Mohamed Morsi was a coup and whether continued aid is therefore illegal under U.S law. Although public opinion polls show that 51 percent of respondents support cutting off aid, to date, no systematic effort has been made to gauge the opinions of scholars who study international relations (IR) for a living.

The Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) Project at the College of William & Mary works to bridge the gap between scholars and the policy community. This spring, for the first time, TRIP conducted two Snap Polls of scholars in the United States about contemporary international events.

The May 2014 Snap Poll included questions on military aid to Egypt. Results show that a large majority, almost 60 percent of IR scholars believe that military aid to Egypt should be decreased or stopped altogether, while 34 percent of experts think aid should be increased or kept about the same. Few scholars support cutting aid altogether.

In an era of fiscal austerity, debate often centers on prioritization of spending. In the United States, conservatives tend to support cutting social programs to ensure continued defense spending, while liberals tend to place more emphasis on funding social programs, at the expense of the defense budget. With these general trends in mind, I anticipated that scholars who identify as liberal on economic issues would be more likely than those who identify as conservative to say that the United States is spending too much on defense (#1 below) and to support decreasing military aid to Egypt (#2). I also expected that those in favor of a smaller defense budget would be opposed to increasing aid to Egypt, and more likely to support decreasing aid (#3).

What do we observe? First, as predicted, a scholar’s economic ideology is correlated with his or her position on defense spending. In our March Snap Poll, we asked about defense spending; 44 percent of conservative IR scholars and 81 percent of liberal IR scholars said that it is too high. At first glance, these findings could suggest that the ideological divide is alive and well in the academy. On closer inspection, however, a different conclusion emerges.

TRIP data show that the vast majority of economically liberal IR scholars support reduced defense spending, but they also show that the gap between economically liberal and economically conservative IR scholars is less dramatic on this issue than one might expect given conventional wisdom. A plurality of conservative IR scholars (44 percent) believes that defense spending is too high, suggesting that there may be more common ground within the academy on the topic of defense spending than conventional wisdom suggests.

Second, economic ideology correlates with views on Egyptian military aid. Approximately one in four self-proclaimed conservatives say military aid to Egypt should be decreased, while about half of liberals agree. At the same time, similar percentages of conservative and liberal IR scholars tend to believe that we should stop aid altogether (twelve and fourteen percent, respectively), or increase aid (five and two percent, respectively). Over 75 percent of both liberal and conservative IR scholars believe that aid to Egypt should be either kept about the same or decreased. Again, the ideological divide seems smaller than suggested by the conventional wisdom.

We see a similar pattern among policymakers in Washington. Although the debate in Congress over aid in Egypt started as a fairly partisan issue, the debate today is defined less by partisanship than it was in the past. Senator McCain has toned down his rhetoric, and Senator Leahy has become more outspoken about the need for continued military aid. Party affiliation is no longer a clear predictor of a politician’s stance on military aid to Egypt.

Finally, IR scholars’ views on the defense budget are not correlated with their positions on Egyptian military aid. Those who think that the United States is spending too much on defense are not statistically more likely than those who think that defense spending is too low or about right to have a particular position on military aid to Egypt.

The absence of a relationship between IR scholars’ responses to questions on the defense budget and on Egyptian military aid suggests that these experts do not think of military aid to Egypt primarily as a budgetary issue; perhaps they view it more as a geo-political issue, divorced from funding concerns. Such a viewpoint would be logical: $1.5 billion sounds like a sizable sum of money, but Egyptian military aid is only about three percent of the foreign aid budget, which itself accounts for just over one percent of the federal budget.

Defense spending and continued provision of military aid are traditionally portrayed as ideologically divisive issues, but IR experts’ views on these issues are less likely to break down along ideological lines than are the opinions of the rest of the American public. Scholars appear to be less ideologically driven, perhaps because they share a knowledge base and educational background that allows them to overcome ideological differences. Further research on the extent to which ideology and party affiliation affect individual views will help us better understand how scholarly opinion can influence policy, as well as how to overcome ideological divides within Congress and the general public on defense spending, military aid, and other foreign policy issues.

Rachel Merriman-Goldring is a Research Assistant at the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) project and an undergraduate student at the College of William & Mary. She can be reached at remerrimangold@email.wm.edu.

Photo: Sebastian Horndasch (cc).