China's censorship of the internet is widely known, but perhaps no day is more sensitive to the "Great Firewall" than June 4th. On this day 25 years ago, a nascent pro-democracy and government reform movement came to a swift and bloody halt in Tiananmen Square, and the Communist Party of China took steps to deeply entrench its place in Chinese government and society. Looking back, the images of the protests are not unfamiliar to us—beyond being some of the most iconic images of from the collapse of the Cold War, the images of hopeful and determined faces gathering in public squares have been repeated from Tunisia to Madrid, Cairo to Brasília. But looking ahead, while China faces much of the same problems of political corruption and economic inequality, the opportunities to recreate the mass protests of 1989 seem to grow more distant with each new term censored from internet search and each new effort toward the depoliticization of Chinese youth.

***

It began with a period of relative political openness. As news of the growing movements for democracy and greater freedoms spread from Eastern Europe, they took hold among Chinese students. When former Communist Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang, a liberal reformer, died in April, students marched in Beijing to Tiananmen Square to mourn and to continue Hu's message of government accountability, freedom of speech, addressing limited job prospects, and fighting corruption in the party elite. Photo by AP.

At the height of the protests, over one million people were gathered in the Square. The government at first allowed the protests to continue, but when a student-led hunger strike galvanized support and the protests began to spread, reaching over 400 cities by mid-May, the military cracked down. Martial law was declared on May 20th, and troops were sent to Beijing. Photo by AP/Sadayuki Mikami.

A report was circulated through the Politburo, describing the protestors as terrorists and counterrevolutionaries. Fears grew in the government that the movement was an attempt by the United States to overthrow the Communist Party and the American military was directly supporting the students. Divisions between moderates and hardliners among the students grew, especially over whether to remain in the Square and whether to abandon non-violence should the military move in. At 4:00 AM on the morning of June, the lights on the Square were turned off, and an announcement made over the government's loudspeaker: "Clearance of the Square begins now." at 4:30 AM, troops moved in, stopping a few meters back from the students to allow those who chose to leave a final chance to do so. Reportedly, those that did leave were not spared, as a tank chased them down as they walked back to Peking University and drove through the line, killing at least 11. Thousands of civilians—especially working class people—tried to re-enter the square later in the morning, but the military opened fire on them, shooting many civilians in the back as they fled down Changan Avenue (the Avenue of Eternal Peace). In other parts of the cities, soldiers met with angry confrontations, as civilians fought back and killed several, hanging their burnt bodies from overpasses. For more information on the timeline of the protests, as well as eyewitness interviews, read the South China Morning Post's interactive feature.

“I saw bodies on the streets,” Reagan Lee, a former senior physics lecturer at Peking University, told news.com.au. “It was horror. After the massacre control was tighter than ever, the government was everywhere and universities were full of spies. People were scared.” According to Mr. Lee, Chinese soldiers would fire on civilians across Chinese cities for days after the crackdown, spreading fear to all corners of the nation.

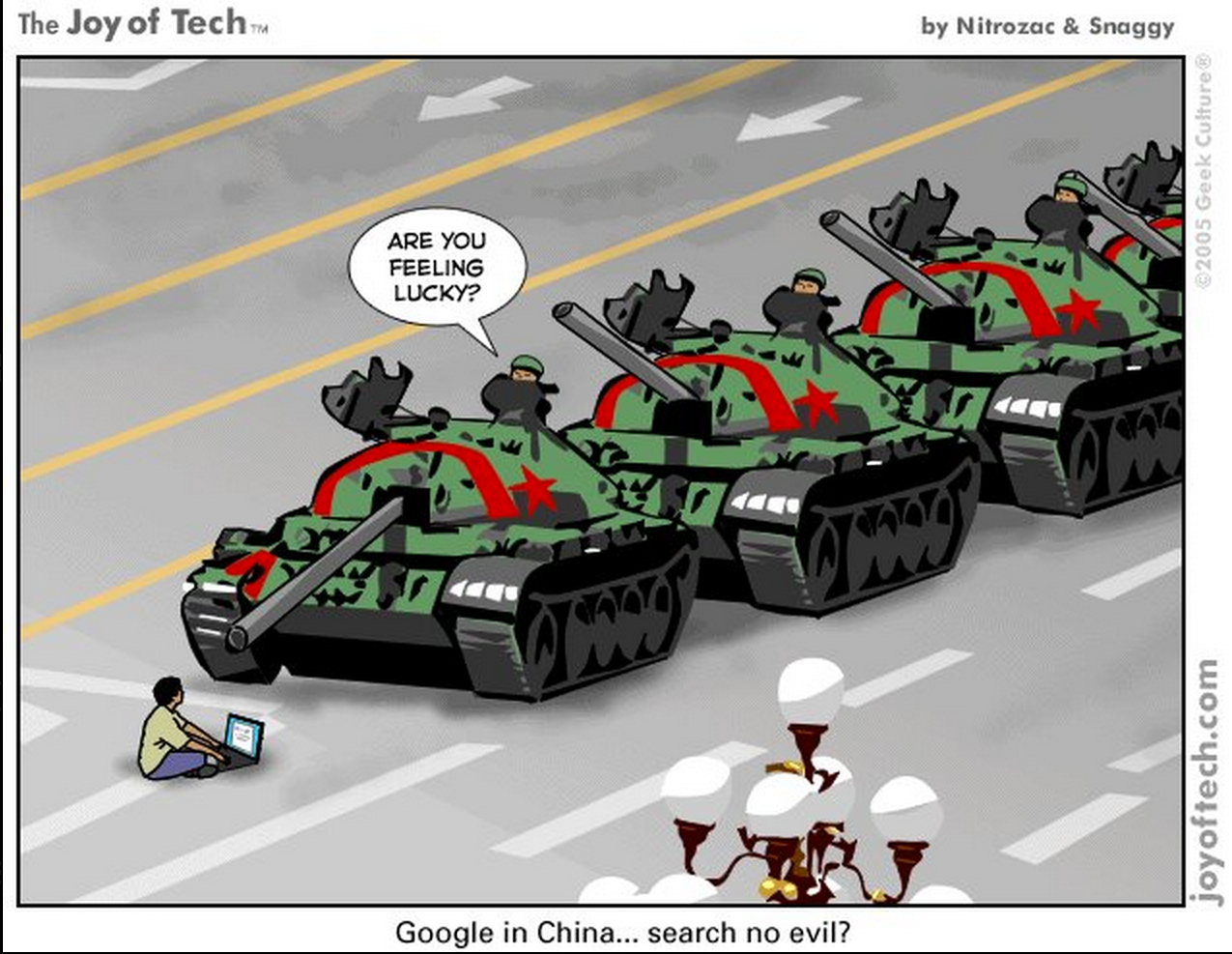

The most iconic image of the Tiananmen Square protests is of a lone man, grocery bags in hand, blocking a column of approaching tanks. According to journalist reports, the tanks attempted to drive around the man several times, but each time he would step in front of the tanks to block the path. Rather than crush the man, the tanks shut off their engines. The man used this opportunity to climb on the front tank, apparently speaking with the soldiers inside. After several minutes of this, the man climbed down, and the tanks powered their engines back on, prompting the man to quickly jump in front of their path again. This impasse continued until the man was dragged into the crowd by two men in blue shirts. Whether they were security or merely concerned citizens is unknown, and the fate of the man is not clear. While some believe he was executed (possibly by firing squad) in the days after the protests—along with an unknown number of other pro-democracy activists—others believe that not even the Central Government know the identity of the man, and he continues to live somewhere in the mainland.

More disheartening, however, is the reactions of Chinese youth to the photo. In an informal survey of Beijing college students done by NPR's Louisa Lim, only 15 out of 100 students had ever seen the photo before. Of those who had seen it, some believed it was of an escaped mental institution patient or a military parade. The short documentary "A Day Forgotten," made in 2005 by Chinese filmmaker Liu Wei, shows the collective silence and unease on the topic.

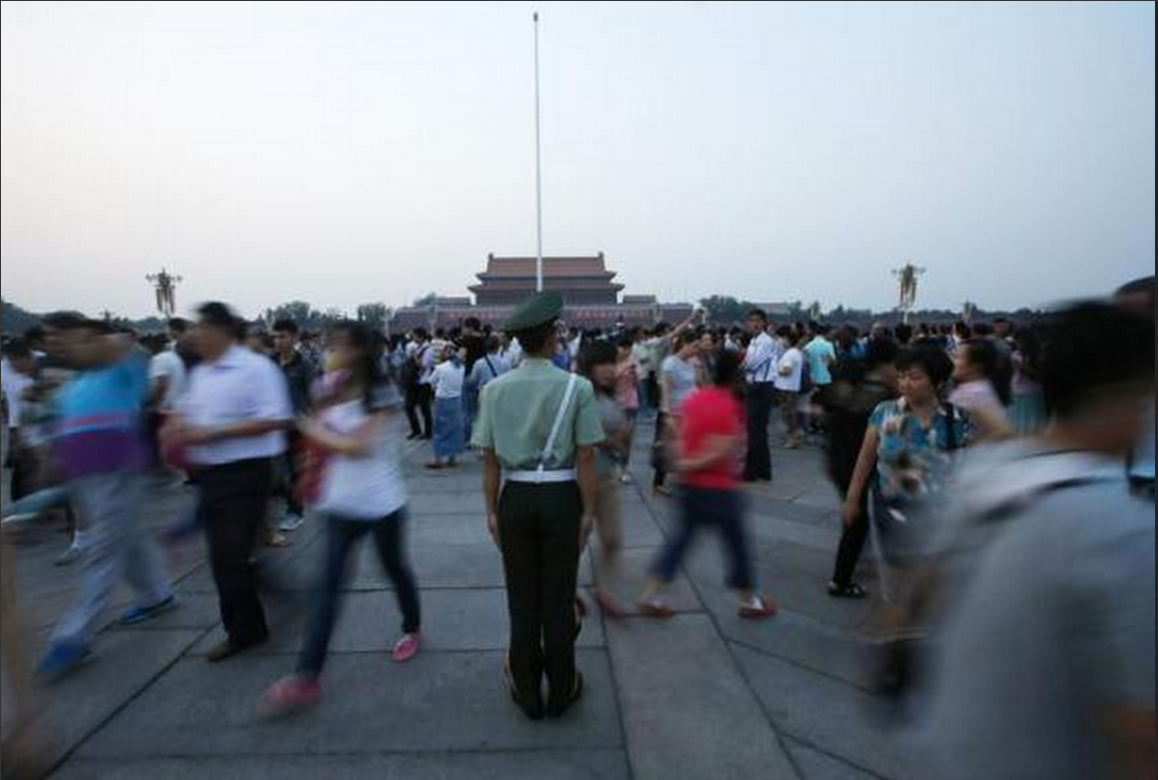

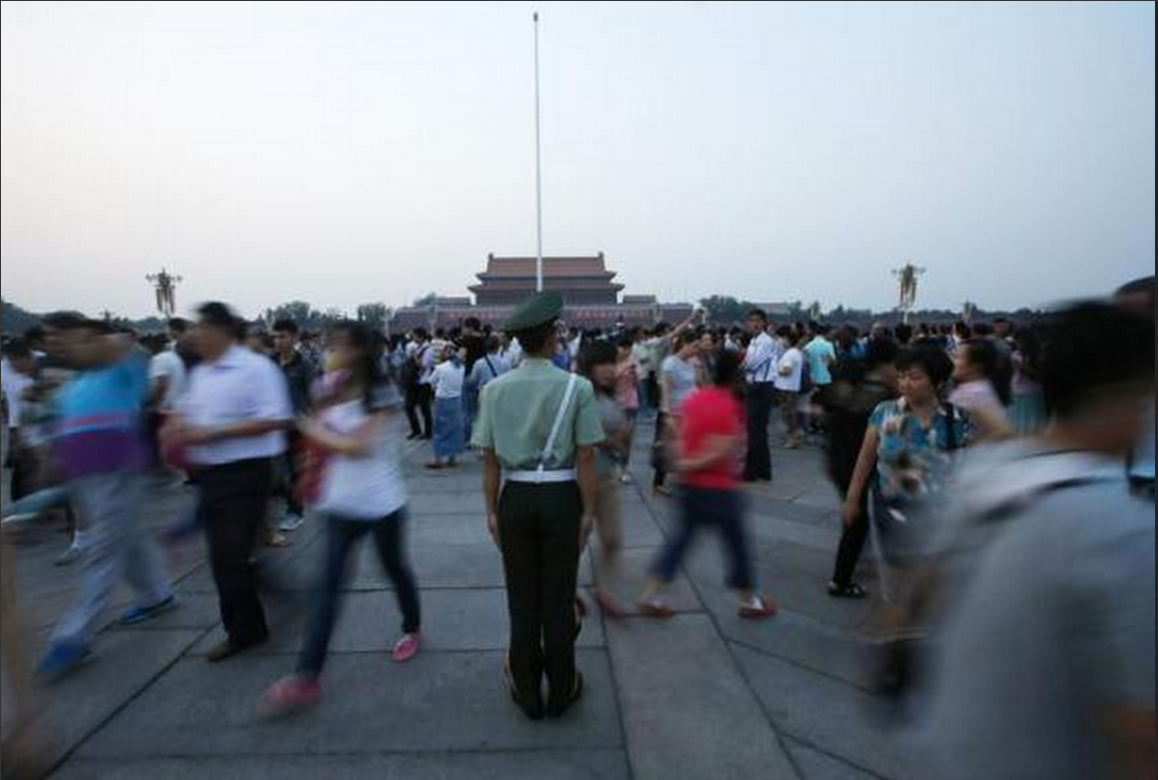

Today, Tiananmen Square is under constant watch, by security cameras, uniformed guards, and plainclothes officers. Protests or demonstrations of any kind are quickly shut down. While there is no consensus on the death toll from the June 4th Incident, Chinese authorities report 241 casualties. This number has been grandly exaggerated by some, including Meet the Press's Tim Russert, who mentioned "tens of thousands" of casualties. While there were many wrongful deaths in Beijing on June 4, 1989, none actually took place inside of Tiananmen Square. In fact, as documents released publicly through Wikileaks and some journalists on the ground suggest, the Chinese government was not worried about the students protesting, but once the working class got involved, the threat of protest could have crippled China and destroyed the political legitimacy of the Communist Party. Photo: Reuters/Kim Kyung-Hoon.

Tiananmen Square is not a mistake the Communist Party of China is about to make twice. During the Arab Spring, news of students setting up tents in Tahrir Square was censored in China, as was several different names for the protests, such as "Jasmine Revolution". Any protests or clashes throughout China quickly is added to the firewall, as is every new term that refers to Tiananmen Square. When the Tank Man image with tanks replaced with giant rubber ducks went viral, those terms were soon banned for a while. On June 4, 2013, the word "today" was reportedly banned, as was the word "tank". This year, the blog "Blocked on Weibo" has reported 64 new terms that are banned for the 25th anniversary.

a global affairs media network

In Photos: 25 Years After Tiananmen Square Protests

June 4, 2014

China's censorship of the internet is widely known, but perhaps no day is more sensitive to the "Great Firewall" than June 4th. On this day 25 years ago, a nascent pro-democracy and government reform movement came to a swift and bloody halt in Tiananmen Square, and the Communist Party of China took steps to deeply entrench its place in Chinese government and society. Looking back, the images of the protests are not unfamiliar to us—beyond being some of the most iconic images of from the collapse of the Cold War, the images of hopeful and determined faces gathering in public squares have been repeated from Tunisia to Madrid, Cairo to Brasília. But looking ahead, while China faces much of the same problems of political corruption and economic inequality, the opportunities to recreate the mass protests of 1989 seem to grow more distant with each new term censored from internet search and each new effort toward the depoliticization of Chinese youth.

***

It began with a period of relative political openness. As news of the growing movements for democracy and greater freedoms spread from Eastern Europe, they took hold among Chinese students. When former Communist Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang, a liberal reformer, died in April, students marched in Beijing to Tiananmen Square to mourn and to continue Hu's message of government accountability, freedom of speech, addressing limited job prospects, and fighting corruption in the party elite. Photo by AP.

At the height of the protests, over one million people were gathered in the Square. The government at first allowed the protests to continue, but when a student-led hunger strike galvanized support and the protests began to spread, reaching over 400 cities by mid-May, the military cracked down. Martial law was declared on May 20th, and troops were sent to Beijing. Photo by AP/Sadayuki Mikami.

A report was circulated through the Politburo, describing the protestors as terrorists and counterrevolutionaries. Fears grew in the government that the movement was an attempt by the United States to overthrow the Communist Party and the American military was directly supporting the students. Divisions between moderates and hardliners among the students grew, especially over whether to remain in the Square and whether to abandon non-violence should the military move in. At 4:00 AM on the morning of June, the lights on the Square were turned off, and an announcement made over the government's loudspeaker: "Clearance of the Square begins now." at 4:30 AM, troops moved in, stopping a few meters back from the students to allow those who chose to leave a final chance to do so. Reportedly, those that did leave were not spared, as a tank chased them down as they walked back to Peking University and drove through the line, killing at least 11. Thousands of civilians—especially working class people—tried to re-enter the square later in the morning, but the military opened fire on them, shooting many civilians in the back as they fled down Changan Avenue (the Avenue of Eternal Peace). In other parts of the cities, soldiers met with angry confrontations, as civilians fought back and killed several, hanging their burnt bodies from overpasses. For more information on the timeline of the protests, as well as eyewitness interviews, read the South China Morning Post's interactive feature.

“I saw bodies on the streets,” Reagan Lee, a former senior physics lecturer at Peking University, told news.com.au. “It was horror. After the massacre control was tighter than ever, the government was everywhere and universities were full of spies. People were scared.” According to Mr. Lee, Chinese soldiers would fire on civilians across Chinese cities for days after the crackdown, spreading fear to all corners of the nation.

The most iconic image of the Tiananmen Square protests is of a lone man, grocery bags in hand, blocking a column of approaching tanks. According to journalist reports, the tanks attempted to drive around the man several times, but each time he would step in front of the tanks to block the path. Rather than crush the man, the tanks shut off their engines. The man used this opportunity to climb on the front tank, apparently speaking with the soldiers inside. After several minutes of this, the man climbed down, and the tanks powered their engines back on, prompting the man to quickly jump in front of their path again. This impasse continued until the man was dragged into the crowd by two men in blue shirts. Whether they were security or merely concerned citizens is unknown, and the fate of the man is not clear. While some believe he was executed (possibly by firing squad) in the days after the protests—along with an unknown number of other pro-democracy activists—others believe that not even the Central Government know the identity of the man, and he continues to live somewhere in the mainland.

More disheartening, however, is the reactions of Chinese youth to the photo. In an informal survey of Beijing college students done by NPR's Louisa Lim, only 15 out of 100 students had ever seen the photo before. Of those who had seen it, some believed it was of an escaped mental institution patient or a military parade. The short documentary "A Day Forgotten," made in 2005 by Chinese filmmaker Liu Wei, shows the collective silence and unease on the topic.

Today, Tiananmen Square is under constant watch, by security cameras, uniformed guards, and plainclothes officers. Protests or demonstrations of any kind are quickly shut down. While there is no consensus on the death toll from the June 4th Incident, Chinese authorities report 241 casualties. This number has been grandly exaggerated by some, including Meet the Press's Tim Russert, who mentioned "tens of thousands" of casualties. While there were many wrongful deaths in Beijing on June 4, 1989, none actually took place inside of Tiananmen Square. In fact, as documents released publicly through Wikileaks and some journalists on the ground suggest, the Chinese government was not worried about the students protesting, but once the working class got involved, the threat of protest could have crippled China and destroyed the political legitimacy of the Communist Party. Photo: Reuters/Kim Kyung-Hoon.

Tiananmen Square is not a mistake the Communist Party of China is about to make twice. During the Arab Spring, news of students setting up tents in Tahrir Square was censored in China, as was several different names for the protests, such as "Jasmine Revolution". Any protests or clashes throughout China quickly is added to the firewall, as is every new term that refers to Tiananmen Square. When the Tank Man image with tanks replaced with giant rubber ducks went viral, those terms were soon banned for a while. On June 4, 2013, the word "today" was reportedly banned, as was the word "tank". This year, the blog "Blocked on Weibo" has reported 64 new terms that are banned for the 25th anniversary.