At the margins of both these world leader gatherings, President Obama will be pushing hard for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a little-known but fairly liberal trade grouping which could put real pressure on China to finally change its mercantilist trade policies and undervalued currency.

Currently, the TPP includes only 4 small economies: Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore. During the past couple of years, Australia, Malaysia, Peru, Vietnam, and the U.S. have been negotiating entry into the group. Now Japan has also announced that it will participate in the negotiations to form what, at least in theory, has come to be perceived as the “gold standard” for trade agreements that would go further than any existing arrangement.

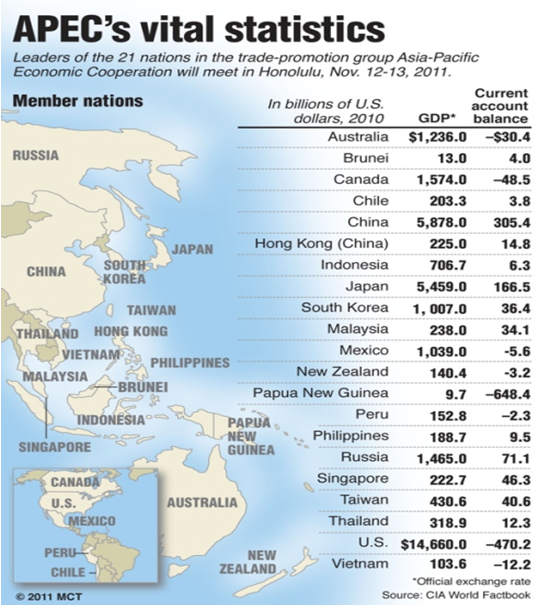

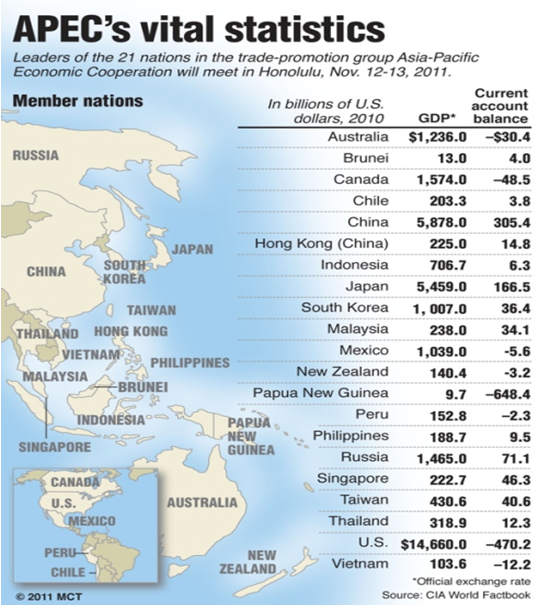

All these Asian summits officially present an excellent opportunity for President Obama to take his effort for economic growth and job creation internationally. Two-way trade between the U.S. and the eight TPP nations totaled $171 billion in 2010, compared with $457 billion with China, $181 billion with Japan and $88 billion with South Korea, according to the U.S. Commerce Department. Overall, the APEC economies account for half of global output, and represent the main target of the president’s efforts to double U.S. exports in the near future.

Unofficially however, U.S. efforts within APEC - and more specifically the nature and composition of the TPP - are designed to confront China on its mercantilist trade policies, especially the manipulation of its currency.

Unofficially however, U.S. efforts within APEC - and more specifically the nature and composition of the TPP - are designed to confront China on its mercantilist trade policies, especially the manipulation of its currency.

What Is So Special About The TPP?

According to Iwan Azis, head of the Asian Development Bank’s regional integration office (quoted in an interview by the FT), the agreement is intended to deal with what he calls “behind the border” issues. These include areas of what could be deemed domestic policy which go beyond the normal scope of trade agreements.

Currently, almost everything other then labor mobility is up for liberalization through the TPP, making it one of the most comprehensive free-trade treaties yet conceived. Beyond the ambitious goal of eliminating all tariffs over 10 years, the most significant areas that are currently negotiated include: government procurement, rules governing the conduct of state-owned enterprises, and intellectual property standards.

The TPP promises something truly groundbreaking: persuading Asian governments to accept new rules on the role of state-owned enterprises, the cornerstone of Asian-style capitalism. State-owned enterprises often benefit from cheap financing or government protection. China, in particular, is often criticized for seeking to ensure the success of national champions to the detriment of free trade and honest competition.

According to Bloomberg, Asian governments operate in many markets through state-owned companies with large bundles of cash reserves at their disposal. They exist both to make a profit and to build state power. Ten years ago, emerging countries added $100 billion a year combined to their reserves. In 2009, they took in $1.6 trillion. Sovereign wealth funds now control 12 percent of investment worldwide, according to the U.S. State Department. Sometimes, state-owned enterprises work in secrecy and without accountability to shareholders, independent boards, and regulators. The lack of transparency puts U.S. companies at a disadvantage.

On the other hand, China undervalues its currency, by pegging the renminbi (RMB) to the dollar at an artificially low level. This, along with other subsidies and mercantilist trade policies, keeps Chinese exports cheap, and thus more attractive to consumers in the U.S. and Europe. Because China is the manufacturing hub for South-East Asia, where most assembling and export happens, China’s artificially undervalued currency is also impacting trade throughout the region.

As a result, other regional countries have pegged their currency to the RMB (Singapore, Taiwan, Malaysia, and of course Hong Kong) in order to compete with Chinese exports, but also to align their production pricing with China. More recently, Japan has been forced to intervene in the foreign currency markets four times during the past 14 months, in order to lower the value of the yen and thus facilitate greater exports for its manufacturing sector.

This is where the TPP can provide leverage for the U.S. The U.S. has not been able to convince China to change its trade and currency policies. Now it must try to put pressure on the other Pacific Rim countries to embrace the U.S. agenda. The timing could not be more opportune.

U.S. Strategy So Far

Over the years, high on the list of U.S. international trade priorities has been getting commitments from China to enact more flexible currency rate standards to help balance trade; respect intellectual property rights; and limit the role of state-owned enterprises in the market. The TPP reads like the U.S. trade agenda with respect to China, now being formalized with some of the most important economies of the region.

So far, China has not been very responsive to U.S. demands for currency appreciation and more domestic (Chinese) consumption. In last year’s APEC meeting, President Obama directly pressed China over its massive exports aided by a cheap RMB, and urged countries with large trade surpluses (like China, Japan, and South Korea) to shift away from their unhealthy dependence on exports and take steps to boost domestic demand. President Obama’s pleas fell on deaf ears (both then and now) as the Chinese leader insisted - as always - that China will make reforms at its own pace.

Unfortunately, singling out China as the worst offender (in mercantilist trade policies) has not worked so far as a strategy. On the other hand, the U.S. has greater leverage and a much different/better relationship with most of the other Asian members of APEC. Therefore, the U.S. should push the partnership to curb currency manipulation, internet censorship, forced intellectual-property sharing, and coerced joint ventures with state-owned companies. If the rest of Asia moves closer to the U.S. model, that could pressure China to do the same. Experts hope that creating a free-trade block of sufficient mass will put pressure on China to join, and thus open and liberalize more of its economy. The idea is for the TPP to be a structure onto which other nations, including possibly South Korea, and eventually even China, could be eventually integrated.

Furthermore, China’s efforts to internationalize the RMB make it all that more pressing to confront them on their undervalued currency. (see, China’s Efforts to Internationalize its Currency) Although it is the most appropriate forum, doing this through APEC will not be easy. China has gotten very good at manipulating international organizations and getting what it wants out of them.

Although active at the technical level, China has not been helpful at the leader’s level with APEC’s efforts to achieve anything even remotely approaching regional free trade. While not wanting to be seen as obstructionist, China can nevertheless be expected to effectively exploit APEC’s inherent inability to act decisively in order to help ensure that the organization never fully achieves any meaningful trade reform. APEC will need strong leadership from the U.S. and President Obama to both address the trade distorting nature of China’s currency policy and strengthen regional free trade.

The "Elephant" in the Room: China

David Gordon of the Eurasia Group recently argued that China has overplayed its hand in Asia, and its rapid growth and aggressive posturing (both economic and military) “is inadvertently driving Asian states to build closer economic and strategic ties with the U.S. and each other.” Over the past 18 months China has taken a very an aggressive tone towards territorial disputes in the South China Sea and elsewhere. Mr. Gordon further argues that Beijing has miscalculated its ability to cater to nationalist feelings domestically without alarming its neighbors, and is now (inadvertently) driving Asian nations to build closer economic and strategic ties with the U.S. and each other.

You know that the Chinese leadership is concerned when commentary in the Chinese press often casts the TPP as an aggressive U.S.-led ploy to squeeze China out of Southeast Asia. Of course this is exactly what China did back in 2005, with the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area. Covering more than 1.8 billion people, this FTA is the world’s largest in terms of population; and amounting to a combined $6 trillion in GDP, the third largest after the EU and NAFTA. The obvious advantage was that such an approach removed the US – and its oftentimes confrontational agenda – from the equation, and it undermined U.S. economic linkages in the region. Now the U.S. is poised to formally accede to East Asia Summit (the ASEAN+3) next week, a move that the other Southeast Asian nations welcome, as they hope that the U.S. could provide a counterweight to China in the region.

Conclusion

Undersecretary of State Robert Hormats was recently quoted as saying: "There's competition between the American economic model and the more state-centered economic model of China and other countries." Many have been arguing for a serious debate on the damaging role of state capitalism on the global economy, and the ideological differences between the U.S./EU rule based global economy and Southeast Asia’s mercantilist trade practices.

Although there is a deeply pragmatic driving force behind the TPP, undoubtedly, it also has an element of seeking to wrest back global trade for nations perceived to play by the rules. The Obama administration might have finally found a trade strategy to deal with China’s undervalued currency and mercantilist economic policies.

Sources:

Trans-Pacific Trade Deal Could Revolutionize Commerce: View by the Editors of Bloomberg BuisnessWeek.

Trans-Pacific Partnership: Far-reaching agreement could form powerful new trade bloc, By David Pilling.

America's Pacific Century, By Hillary Clinton.

Obama heads to Asia focused on China’s power, by David Nakamura and William Wan.

A trade opportunity Washington shouldn’t pass up, by David Gordon.

Nasos Mihalakas is an adjunct professor at UNYT, teaching International and Commercial Law, and a contributor for The Diplomatic Courier and the Foreign Policy Association. In the past he worked as a policy analyst for both a Congressional Commission advising members of Congress on the impact of trade with China on the U.S. economy, and for the U.S. Department of Commerce investigating unfair trade practices and foreign market access restrictions. Contact: nasos.mihalakas@gmail.com

a global affairs media network

APEC and the TPP: The Best Way to Deal with China’s Undervalued Currency

November 14, 2011

At the margins of both these world leader gatherings, President Obama will be pushing hard for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a little-known but fairly liberal trade grouping which could put real pressure on China to finally change its mercantilist trade policies and undervalued currency.

Currently, the TPP includes only 4 small economies: Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore. During the past couple of years, Australia, Malaysia, Peru, Vietnam, and the U.S. have been negotiating entry into the group. Now Japan has also announced that it will participate in the negotiations to form what, at least in theory, has come to be perceived as the “gold standard” for trade agreements that would go further than any existing arrangement.

All these Asian summits officially present an excellent opportunity for President Obama to take his effort for economic growth and job creation internationally. Two-way trade between the U.S. and the eight TPP nations totaled $171 billion in 2010, compared with $457 billion with China, $181 billion with Japan and $88 billion with South Korea, according to the U.S. Commerce Department. Overall, the APEC economies account for half of global output, and represent the main target of the president’s efforts to double U.S. exports in the near future.

Unofficially however, U.S. efforts within APEC - and more specifically the nature and composition of the TPP - are designed to confront China on its mercantilist trade policies, especially the manipulation of its currency.

Unofficially however, U.S. efforts within APEC - and more specifically the nature and composition of the TPP - are designed to confront China on its mercantilist trade policies, especially the manipulation of its currency.

What Is So Special About The TPP?

According to Iwan Azis, head of the Asian Development Bank’s regional integration office (quoted in an interview by the FT), the agreement is intended to deal with what he calls “behind the border” issues. These include areas of what could be deemed domestic policy which go beyond the normal scope of trade agreements.

Currently, almost everything other then labor mobility is up for liberalization through the TPP, making it one of the most comprehensive free-trade treaties yet conceived. Beyond the ambitious goal of eliminating all tariffs over 10 years, the most significant areas that are currently negotiated include: government procurement, rules governing the conduct of state-owned enterprises, and intellectual property standards.

The TPP promises something truly groundbreaking: persuading Asian governments to accept new rules on the role of state-owned enterprises, the cornerstone of Asian-style capitalism. State-owned enterprises often benefit from cheap financing or government protection. China, in particular, is often criticized for seeking to ensure the success of national champions to the detriment of free trade and honest competition.

According to Bloomberg, Asian governments operate in many markets through state-owned companies with large bundles of cash reserves at their disposal. They exist both to make a profit and to build state power. Ten years ago, emerging countries added $100 billion a year combined to their reserves. In 2009, they took in $1.6 trillion. Sovereign wealth funds now control 12 percent of investment worldwide, according to the U.S. State Department. Sometimes, state-owned enterprises work in secrecy and without accountability to shareholders, independent boards, and regulators. The lack of transparency puts U.S. companies at a disadvantage.

On the other hand, China undervalues its currency, by pegging the renminbi (RMB) to the dollar at an artificially low level. This, along with other subsidies and mercantilist trade policies, keeps Chinese exports cheap, and thus more attractive to consumers in the U.S. and Europe. Because China is the manufacturing hub for South-East Asia, where most assembling and export happens, China’s artificially undervalued currency is also impacting trade throughout the region.

As a result, other regional countries have pegged their currency to the RMB (Singapore, Taiwan, Malaysia, and of course Hong Kong) in order to compete with Chinese exports, but also to align their production pricing with China. More recently, Japan has been forced to intervene in the foreign currency markets four times during the past 14 months, in order to lower the value of the yen and thus facilitate greater exports for its manufacturing sector.

This is where the TPP can provide leverage for the U.S. The U.S. has not been able to convince China to change its trade and currency policies. Now it must try to put pressure on the other Pacific Rim countries to embrace the U.S. agenda. The timing could not be more opportune.

U.S. Strategy So Far

Over the years, high on the list of U.S. international trade priorities has been getting commitments from China to enact more flexible currency rate standards to help balance trade; respect intellectual property rights; and limit the role of state-owned enterprises in the market. The TPP reads like the U.S. trade agenda with respect to China, now being formalized with some of the most important economies of the region.

So far, China has not been very responsive to U.S. demands for currency appreciation and more domestic (Chinese) consumption. In last year’s APEC meeting, President Obama directly pressed China over its massive exports aided by a cheap RMB, and urged countries with large trade surpluses (like China, Japan, and South Korea) to shift away from their unhealthy dependence on exports and take steps to boost domestic demand. President Obama’s pleas fell on deaf ears (both then and now) as the Chinese leader insisted - as always - that China will make reforms at its own pace.

Unfortunately, singling out China as the worst offender (in mercantilist trade policies) has not worked so far as a strategy. On the other hand, the U.S. has greater leverage and a much different/better relationship with most of the other Asian members of APEC. Therefore, the U.S. should push the partnership to curb currency manipulation, internet censorship, forced intellectual-property sharing, and coerced joint ventures with state-owned companies. If the rest of Asia moves closer to the U.S. model, that could pressure China to do the same. Experts hope that creating a free-trade block of sufficient mass will put pressure on China to join, and thus open and liberalize more of its economy. The idea is for the TPP to be a structure onto which other nations, including possibly South Korea, and eventually even China, could be eventually integrated.

Furthermore, China’s efforts to internationalize the RMB make it all that more pressing to confront them on their undervalued currency. (see, China’s Efforts to Internationalize its Currency) Although it is the most appropriate forum, doing this through APEC will not be easy. China has gotten very good at manipulating international organizations and getting what it wants out of them.

Although active at the technical level, China has not been helpful at the leader’s level with APEC’s efforts to achieve anything even remotely approaching regional free trade. While not wanting to be seen as obstructionist, China can nevertheless be expected to effectively exploit APEC’s inherent inability to act decisively in order to help ensure that the organization never fully achieves any meaningful trade reform. APEC will need strong leadership from the U.S. and President Obama to both address the trade distorting nature of China’s currency policy and strengthen regional free trade.

The "Elephant" in the Room: China

David Gordon of the Eurasia Group recently argued that China has overplayed its hand in Asia, and its rapid growth and aggressive posturing (both economic and military) “is inadvertently driving Asian states to build closer economic and strategic ties with the U.S. and each other.” Over the past 18 months China has taken a very an aggressive tone towards territorial disputes in the South China Sea and elsewhere. Mr. Gordon further argues that Beijing has miscalculated its ability to cater to nationalist feelings domestically without alarming its neighbors, and is now (inadvertently) driving Asian nations to build closer economic and strategic ties with the U.S. and each other.

You know that the Chinese leadership is concerned when commentary in the Chinese press often casts the TPP as an aggressive U.S.-led ploy to squeeze China out of Southeast Asia. Of course this is exactly what China did back in 2005, with the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area. Covering more than 1.8 billion people, this FTA is the world’s largest in terms of population; and amounting to a combined $6 trillion in GDP, the third largest after the EU and NAFTA. The obvious advantage was that such an approach removed the US – and its oftentimes confrontational agenda – from the equation, and it undermined U.S. economic linkages in the region. Now the U.S. is poised to formally accede to East Asia Summit (the ASEAN+3) next week, a move that the other Southeast Asian nations welcome, as they hope that the U.S. could provide a counterweight to China in the region.

Conclusion

Undersecretary of State Robert Hormats was recently quoted as saying: "There's competition between the American economic model and the more state-centered economic model of China and other countries." Many have been arguing for a serious debate on the damaging role of state capitalism on the global economy, and the ideological differences between the U.S./EU rule based global economy and Southeast Asia’s mercantilist trade practices.

Although there is a deeply pragmatic driving force behind the TPP, undoubtedly, it also has an element of seeking to wrest back global trade for nations perceived to play by the rules. The Obama administration might have finally found a trade strategy to deal with China’s undervalued currency and mercantilist economic policies.

Sources:

Trans-Pacific Trade Deal Could Revolutionize Commerce: View by the Editors of Bloomberg BuisnessWeek.

Trans-Pacific Partnership: Far-reaching agreement could form powerful new trade bloc, By David Pilling.

America's Pacific Century, By Hillary Clinton.

Obama heads to Asia focused on China’s power, by David Nakamura and William Wan.

A trade opportunity Washington shouldn’t pass up, by David Gordon.

Nasos Mihalakas is an adjunct professor at UNYT, teaching International and Commercial Law, and a contributor for The Diplomatic Courier and the Foreign Policy Association. In the past he worked as a policy analyst for both a Congressional Commission advising members of Congress on the impact of trade with China on the U.S. economy, and for the U.S. Department of Commerce investigating unfair trade practices and foreign market access restrictions. Contact: nasos.mihalakas@gmail.com