.

In 1796, President George Washington delivered his farewell address, a goodbye to public service, which also included his advice on how the fledgling nation ought to progress to assure continued peace and prosperity. One of the more noteworthy clauses of that address was that the United States ought to “steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world,” to avoid entanglement in affairs that don’t involve America.

Over a century later, in 1918, at the conclusion of the First World War, President Woodrow Wilson delivered the Fourteen Points detailing how the entire international community ought to proceed, to avoid a return to such devastation. First among the points was his call for “open covenants of peace,” putting an end to secret dealings and alliances so that diplomatic relations would “proceed always frankly and in the public view.”

Since Wilson’s early 20th Century warning, nearly another full century has passed—one that finds the United States and the world at large as entangled as ever. One of the more confusing regions to navigate is the Caucasus, located “between the Black Sea (west) and the Caspian Sea (east) and occupied by Russia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia,” with Turkey, Iran, and several Middle Eastern States just to the South.

While this collection of nations has had no shortage of internal and external disputes, an old grudge has been resurfacing between “Armenia and Azerbaijan, and as this year progresses, chances of a resumption of hostilities between the two countries will remain high.” The two states have been disputing rights to a territory known as the Nagorno-Karabakh, and indeed, fought a war over that very area from 1988-1994. The conflict has its “roots dating back well over a century into competition between Christian Armenia” and Muslim Azerbaijan.

At first glance, this may appear to be just another territorial dispute—which the world certainly has in abundance. However, when factoring in the other states and the alliances involved, this specific territorial dispute could have global consequences.

Formerly the Soviet protector to the whole region, the modern Russian Federation has quite a large stake in this particular dispute. At the conclusion of the 1988-94 War, it was the Russians who initiated the truce, and today it is still widely believed that the Russians are the only ones with enough regional clout to keep tensions cool. One previous idea entertained by Russia (and which is thought to still be in discussion) is the Lavrov Plan. However, it’s one to which Armenia is hostile to, as it calls for them to “cede five of its seven regions surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan in exchange for a peacekeeping force led by Russia.”

Armenia is not the only country in the region to find itself opposing Russia. In 2008, Russia engaged in a 5-day military conflict with Georgia, which ended in Russia’s withdrawal, along with condemnation from the United States, and an investigation by the International Criminal Court for War Crimes. In addition to this past military faceoff, Georgia has continued to find itself in tricky economic deals, given the hostilities between the other Caucasus states, and soon, may have to come down officially for one side over another.

Russia still easily outmatches these two smaller nations in military might and political influence; but here enters Iran. The Orthodox Christian Armenia and the Islamic fundamentalist Iran—though seemingly odd bedfellows—have found themselves paired by geopolitical forces. Iran has not only been at odds with Russia for regional influence, but has its historic rivalry with Turkey, and “strained relations with Azerbaijan over that country’s rejection of an Islamic order.” Thus, reaching out to Armenia made sense, and Armenia has been happy to accept their friendship ever since.

Perhaps most clear, are the hostilities between Armenia and Turkey. This attitude is easily understood in light of Turkey’s resentment towards its former Ottoman subjects, and Armenia’s pursuit of “recognition of the 1915 killings as genocide”—a claim much of the world has failed to recognize, including the United States, but not Russia and 25 other nations.

Most of the refusal to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide comes from Turkey’s importance in geopolitics. In fact, hostility towards Turkey is an issue on which Russia and Armenia have found common ground in the past—a mutual feeling that even saw thousands of Russian troops housed in Armenia at two Russian military bases as a deterrent—a move that upset some of Turkey’s allies, along with Armenian supporters such as the United States.

The United States is not the only distant ally that has seen itself pulled into this tinderbox of religious, ethnic, and territorial disputes. In the midst of the Iranian conflicts with Azerbaijan, the more secular Muslim Azeris found an ally in Iran’s most hated enemy: the Israelis. For Azerbaijan, a friendship with Israel not only gives them an ally against Iran, but also a sophisticated military trading partner to leverage against Russian arms sales in the region. In turn, for Israel, having any ally is beneficial, but especially a Muslim nation that shares a border with Iran.

This arrangement has its drawbacks for Armenian-Israeli ties, however. Israeli Jews and Armenians have long been thought to be kindred spirits due to their mutual historical traumas. As well, a large number of Armenians reside comfortably in Israel. But due to Israel’s political need to retain positive ties with Turkey, and its opposition to Iran, it’s unclear if good relations can persist with Armenia.

While Wilson sought to amend Washington’s warnings concerning no permanent alliances, it is clear that such avoidance of secret alliances has not made the world any more stable. In this small territorial conflict in this Eurasian region, players near and far have been dragged into the game, and if tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan continue to rise, this tinderbox could very well cease to merely smolder, but burst into flame.

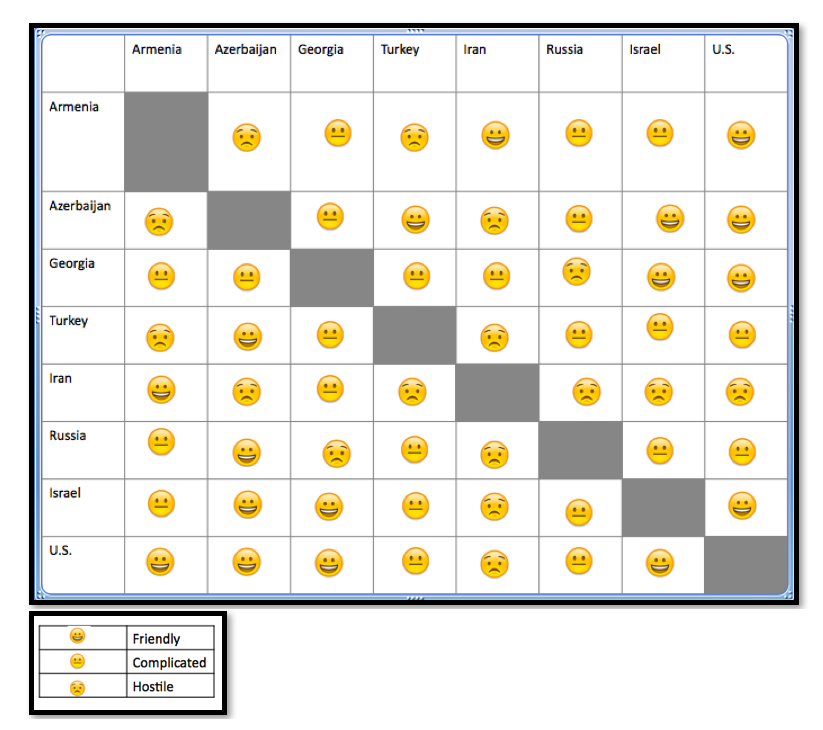

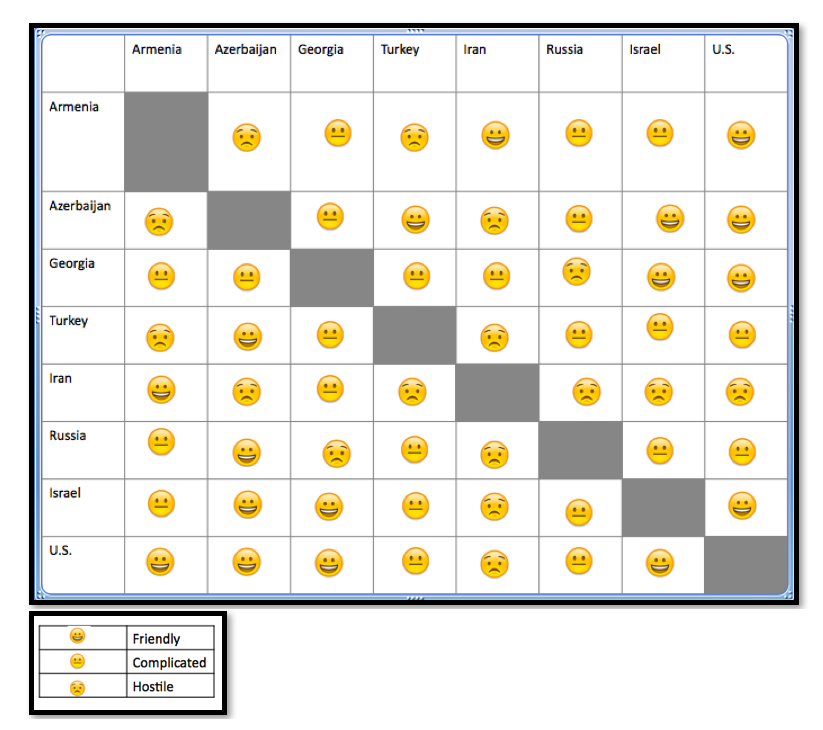

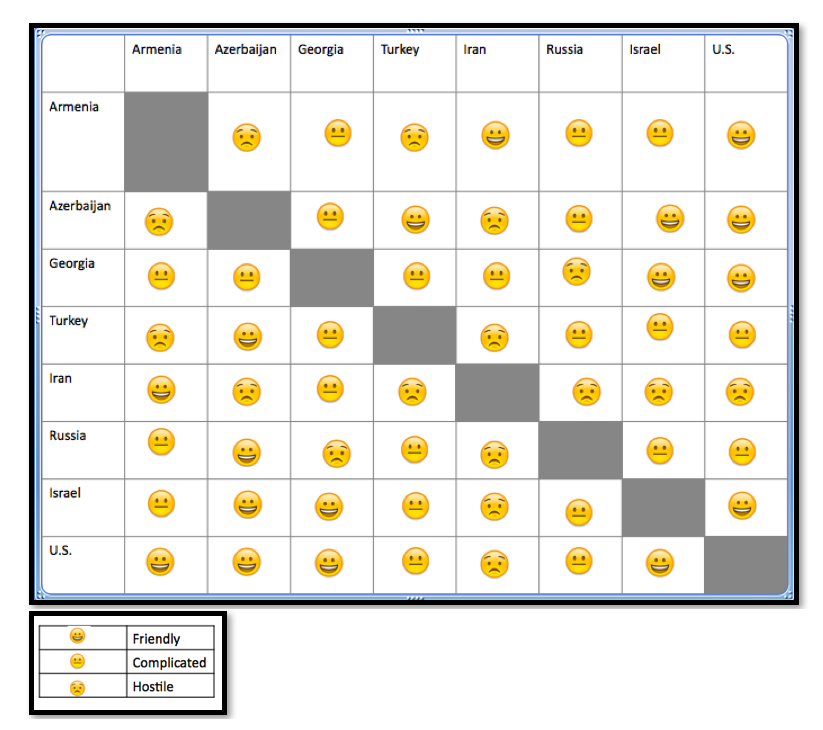

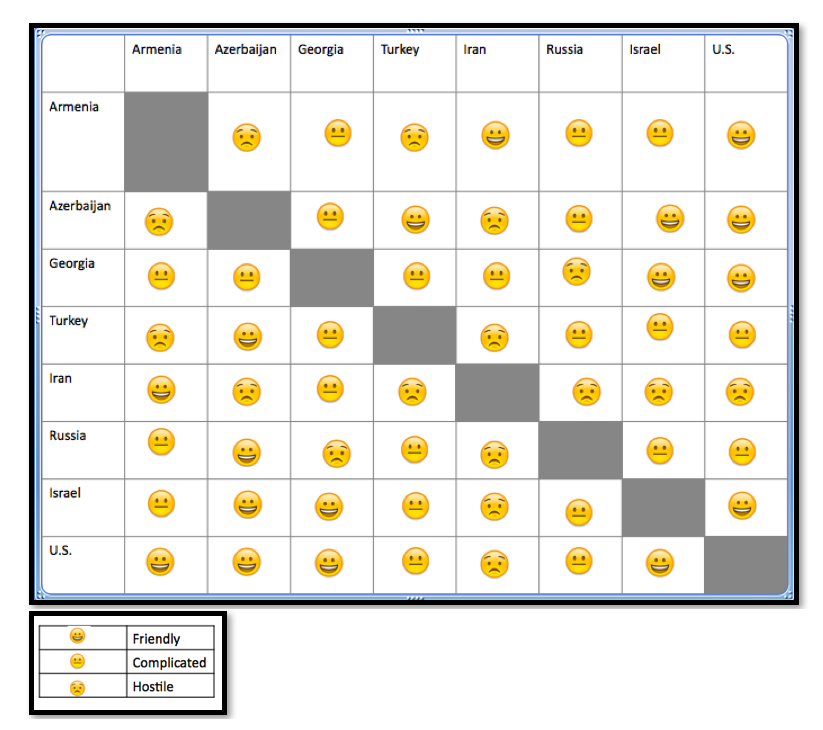

If the multitude of relationships is still unclear, please refer to the below Caucasus Friendship Chart*, inspired by the “Middle East Friendship Chart, ” by Joshua Keating and Chris Kirk.

*As of March 2017, subject to geopolitical shifts.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the U.S. government, or any other government or institution.

About the author: Justin Leopold-Cohen completed his undergraduate degree in American History from Clark University. He later interned with the Hudson Institute’s Center for Political and Military Analysis, and now is involved in graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, nearing the completion of a Master’s Degree in Global Security Studies.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

*As of March 2017, subject to geopolitical shifts.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the U.S. government, or any other government or institution.

About the author: Justin Leopold-Cohen completed his undergraduate degree in American History from Clark University. He later interned with the Hudson Institute’s Center for Political and Military Analysis, and now is involved in graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, nearing the completion of a Master’s Degree in Global Security Studies.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

*As of March 2017, subject to geopolitical shifts.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the U.S. government, or any other government or institution.

About the author: Justin Leopold-Cohen completed his undergraduate degree in American History from Clark University. He later interned with the Hudson Institute’s Center for Political and Military Analysis, and now is involved in graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, nearing the completion of a Master’s Degree in Global Security Studies.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

*As of March 2017, subject to geopolitical shifts.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the U.S. government, or any other government or institution.

About the author: Justin Leopold-Cohen completed his undergraduate degree in American History from Clark University. He later interned with the Hudson Institute’s Center for Political and Military Analysis, and now is involved in graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, nearing the completion of a Master’s Degree in Global Security Studies.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.

a global affairs media network

Tracing Knots: Tangled Alliances in the Tinderbox Known as the Caucasus

|

May 12, 2017

In 1796, President George Washington delivered his farewell address, a goodbye to public service, which also included his advice on how the fledgling nation ought to progress to assure continued peace and prosperity. One of the more noteworthy clauses of that address was that the United States ought to “steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world,” to avoid entanglement in affairs that don’t involve America.

Over a century later, in 1918, at the conclusion of the First World War, President Woodrow Wilson delivered the Fourteen Points detailing how the entire international community ought to proceed, to avoid a return to such devastation. First among the points was his call for “open covenants of peace,” putting an end to secret dealings and alliances so that diplomatic relations would “proceed always frankly and in the public view.”

Since Wilson’s early 20th Century warning, nearly another full century has passed—one that finds the United States and the world at large as entangled as ever. One of the more confusing regions to navigate is the Caucasus, located “between the Black Sea (west) and the Caspian Sea (east) and occupied by Russia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia,” with Turkey, Iran, and several Middle Eastern States just to the South.

While this collection of nations has had no shortage of internal and external disputes, an old grudge has been resurfacing between “Armenia and Azerbaijan, and as this year progresses, chances of a resumption of hostilities between the two countries will remain high.” The two states have been disputing rights to a territory known as the Nagorno-Karabakh, and indeed, fought a war over that very area from 1988-1994. The conflict has its “roots dating back well over a century into competition between Christian Armenia” and Muslim Azerbaijan.

At first glance, this may appear to be just another territorial dispute—which the world certainly has in abundance. However, when factoring in the other states and the alliances involved, this specific territorial dispute could have global consequences.

Formerly the Soviet protector to the whole region, the modern Russian Federation has quite a large stake in this particular dispute. At the conclusion of the 1988-94 War, it was the Russians who initiated the truce, and today it is still widely believed that the Russians are the only ones with enough regional clout to keep tensions cool. One previous idea entertained by Russia (and which is thought to still be in discussion) is the Lavrov Plan. However, it’s one to which Armenia is hostile to, as it calls for them to “cede five of its seven regions surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan in exchange for a peacekeeping force led by Russia.”

Armenia is not the only country in the region to find itself opposing Russia. In 2008, Russia engaged in a 5-day military conflict with Georgia, which ended in Russia’s withdrawal, along with condemnation from the United States, and an investigation by the International Criminal Court for War Crimes. In addition to this past military faceoff, Georgia has continued to find itself in tricky economic deals, given the hostilities between the other Caucasus states, and soon, may have to come down officially for one side over another.

Russia still easily outmatches these two smaller nations in military might and political influence; but here enters Iran. The Orthodox Christian Armenia and the Islamic fundamentalist Iran—though seemingly odd bedfellows—have found themselves paired by geopolitical forces. Iran has not only been at odds with Russia for regional influence, but has its historic rivalry with Turkey, and “strained relations with Azerbaijan over that country’s rejection of an Islamic order.” Thus, reaching out to Armenia made sense, and Armenia has been happy to accept their friendship ever since.

Perhaps most clear, are the hostilities between Armenia and Turkey. This attitude is easily understood in light of Turkey’s resentment towards its former Ottoman subjects, and Armenia’s pursuit of “recognition of the 1915 killings as genocide”—a claim much of the world has failed to recognize, including the United States, but not Russia and 25 other nations.

Most of the refusal to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide comes from Turkey’s importance in geopolitics. In fact, hostility towards Turkey is an issue on which Russia and Armenia have found common ground in the past—a mutual feeling that even saw thousands of Russian troops housed in Armenia at two Russian military bases as a deterrent—a move that upset some of Turkey’s allies, along with Armenian supporters such as the United States.

The United States is not the only distant ally that has seen itself pulled into this tinderbox of religious, ethnic, and territorial disputes. In the midst of the Iranian conflicts with Azerbaijan, the more secular Muslim Azeris found an ally in Iran’s most hated enemy: the Israelis. For Azerbaijan, a friendship with Israel not only gives them an ally against Iran, but also a sophisticated military trading partner to leverage against Russian arms sales in the region. In turn, for Israel, having any ally is beneficial, but especially a Muslim nation that shares a border with Iran.

This arrangement has its drawbacks for Armenian-Israeli ties, however. Israeli Jews and Armenians have long been thought to be kindred spirits due to their mutual historical traumas. As well, a large number of Armenians reside comfortably in Israel. But due to Israel’s political need to retain positive ties with Turkey, and its opposition to Iran, it’s unclear if good relations can persist with Armenia.

While Wilson sought to amend Washington’s warnings concerning no permanent alliances, it is clear that such avoidance of secret alliances has not made the world any more stable. In this small territorial conflict in this Eurasian region, players near and far have been dragged into the game, and if tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan continue to rise, this tinderbox could very well cease to merely smolder, but burst into flame.

If the multitude of relationships is still unclear, please refer to the below Caucasus Friendship Chart*, inspired by the “Middle East Friendship Chart, ” by Joshua Keating and Chris Kirk.

*As of March 2017, subject to geopolitical shifts.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the U.S. government, or any other government or institution.

About the author: Justin Leopold-Cohen completed his undergraduate degree in American History from Clark University. He later interned with the Hudson Institute’s Center for Political and Military Analysis, and now is involved in graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, nearing the completion of a Master’s Degree in Global Security Studies.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

*As of March 2017, subject to geopolitical shifts.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the U.S. government, or any other government or institution.

About the author: Justin Leopold-Cohen completed his undergraduate degree in American History from Clark University. He later interned with the Hudson Institute’s Center for Political and Military Analysis, and now is involved in graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, nearing the completion of a Master’s Degree in Global Security Studies.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

*As of March 2017, subject to geopolitical shifts.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the U.S. government, or any other government or institution.

About the author: Justin Leopold-Cohen completed his undergraduate degree in American History from Clark University. He later interned with the Hudson Institute’s Center for Political and Military Analysis, and now is involved in graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, nearing the completion of a Master’s Degree in Global Security Studies.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

*As of March 2017, subject to geopolitical shifts.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the U.S. government, or any other government or institution.

About the author: Justin Leopold-Cohen completed his undergraduate degree in American History from Clark University. He later interned with the Hudson Institute’s Center for Political and Military Analysis, and now is involved in graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, nearing the completion of a Master’s Degree in Global Security Studies.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.