.

“We are determined to foster peaceful, just and inclusive societies which are free from fear and violence” states the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. At global level the normative debate on the linkages between peace and development has been won with the identification of peace as one of five cross cutting priorities in new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the inclusion of SDG 16 on peace, justice and accountable governance. But – already 2% of the way to 2030 - what do those working on the intersection between peace and development need to do next?

The past is just the prologue

We should first recognise that momentum is with us, with regards to both reductions in violence and the factors underpinning positive peace. Peaking in the late 1980s and early 90s, the number of armed conflicts has fallen significantly. The risk of inter-state war – and the levels of carnage seen in two world wars – has also declined. While stubbornly high in some contexts, homicide rates have fallen. Measures of access to justice by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) initiative show progress for both men and women over the last 50 years. The number of democracies increased from 30 in 1959 to 87 in 2009. We have also seen a significant expansion in measures of freedoms of expression in the same period.

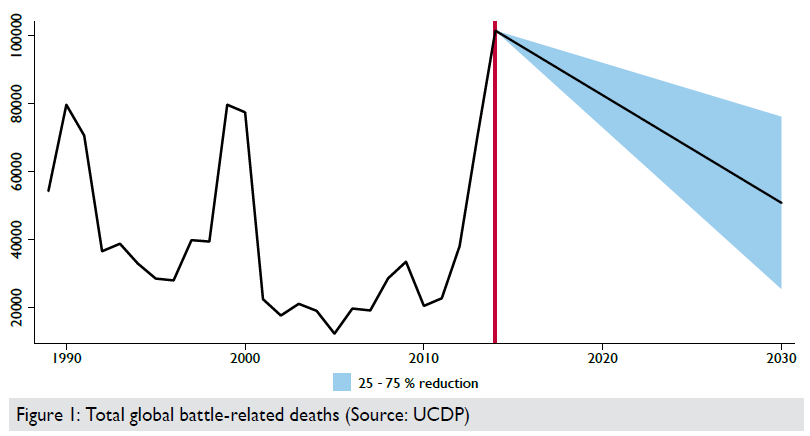

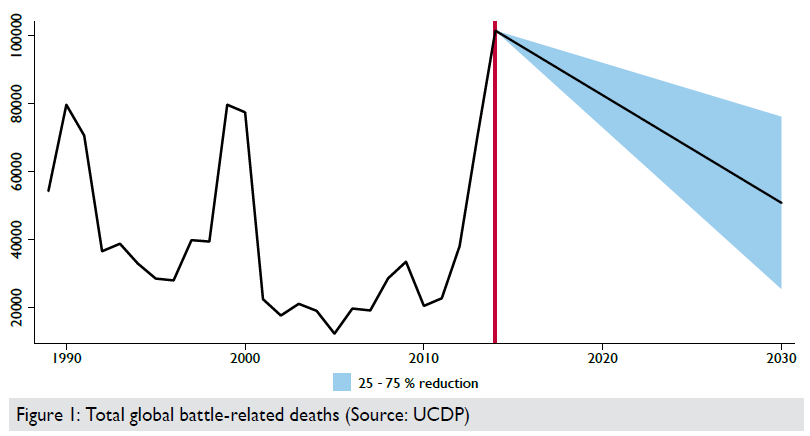

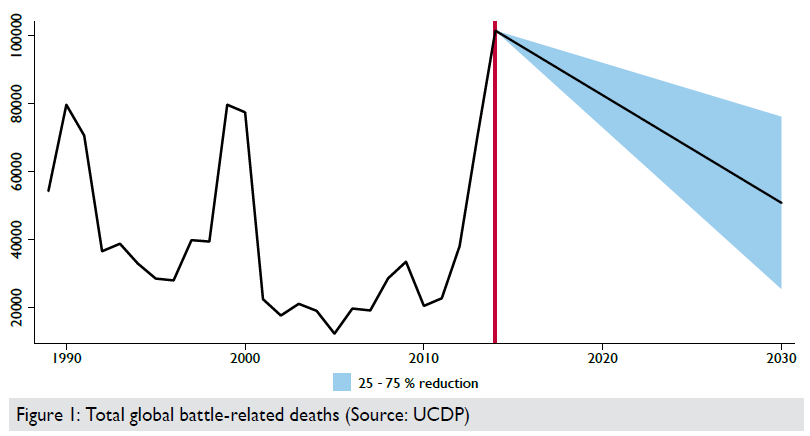

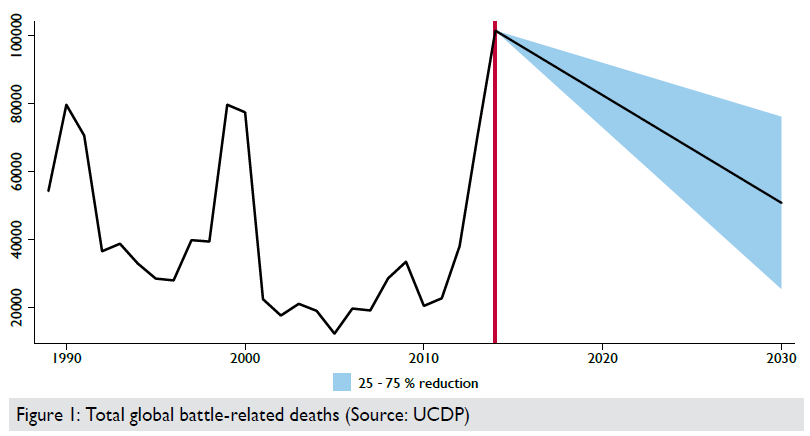

We must, nonetheless, be sober about the scale of the challenge ahead. We met the target of halving extreme poverty in the MDG period but the SDGs aim to now end extreme poverty. Those living in extreme poverty will increasingly be concentrated in countries experiencing or at risk of conflict. Worryingly, the number of conflicts jumped from a low of five in 2010 to 11 in 2014, the most deadly year in the past 20. Syria accounts for many of these deaths, but of “the ten conflicts with the most fatalities in 2013, eight became more violent in 2014.” Using 2014 as our baseline year, we will not get back down to 2010 levels by 2030 even with a 75% reduction in conflict deaths.

Other recent indicators of positive peace are worrying: One 2010 study suggests that even the 20 fastest reforming ‘fragile’ states would still take 41 years to reach an average score on the World Bank’s rule of law indicator. Over the past 10 years, 105 countries have seen a net decline in democracy as measured by Freedom House; only 61 have experienced a net improvement. Major protests have occurred around the world with increasing frequency since the second half of the 2000s. As for fundamental freedoms, more than 60 countries have passed or drafted laws that curtail the activity of civil society in the last three years while two-thirds of the 180 countries surveyed for the 2015 World Press Freedom Index performed less well than in the previous year. Overall, taking a broad view of positive peace over the past eight years, the Global Peace Index has documented small but significant declines.

It is debatable whether the momentum of the past 50 years or so is slowing or even reversing. Spikes in conflict deaths, challenges to democracy, or restrictions on freedoms are not necessarily representative of long-term future trends. Moreover, not all data sets point in the same direction (V-dem, for example, does not present as pessimistic a view on democracy as Freedom House) and we know that data can only tell an incomplete story. Either way, however, it is clear that making progress towards Goal 16 will not happen in the absence of concerted international action.

A glance at the global environment hardly installs confidence. To start with, we will increasingly face transnational issues that drive conflict, including illicit financial flows, arms transfers, the drugs trade, climate change and terrorism. On some of these issues the international community has failed to act, on others action has done more harm than good. Meanwhile international relations are uncertain and our systems of global governance are under immense strain, as the UN Security Council’s impasse on Syria tragically demonstrates. In the West, continued austerity risks discouraging attention to global development while the politics of fear encourages closed societies who build walls and the adoption of a narrow and short-sighed definition of the national interest.

Getting back on track

Resignation is one option. Another is to think about how the 2030 Agenda’s commitment to peace and Goal 16 can be used. Significant political capital was invested in getting agreement on the goal. This can now be spent on generating momentum for action well beyond New York. We can talk about root causes, but we ultimately know that progress on the issues contained in Goal 16 will come down to political leadership at domestic level within both state and society. Consensus within the development and peacebuilding community on the need to “work politically” risks becoming meaningless if interpreted as merely understanding local politics and working with the grain of the status quo. We should go further and use Goal 16 to channel international support to change-makers at national level, whether they are reformers in the ministry of justice, human rights defenders, or businesses intent on strengthening the rule of law. Working politically may mean taking sides, but 193 member states have signed up to the commitments and language of Goal 16, creating a legitimate basis for engagement across a host of contexts and with a range of actors.

With this in mind, it will be important to acknowledge that specific aspects of Goal 16 will be relevant to different actors in different contexts and at different junctures in time. This will mean working flexibly and avoiding the temptation to replicate template programming approaches from one context to another. And the 15 year time span of the SDGs means we can work to sensible long-term time horizons rather than merely hopping from one project to the next. In addition, we now have a means for tracking progress: the global SDG indicators are perfect, but they will generate new data on issues not traditionally tracked officially or in a way that is comparable between countries. This data will be the currency of accountability processes. The world will need to make significant investments in data gathering capacities, both within national statistical systems but also among multilateral agencies and civil society with the overall aim of creating pluralistic data ecosystems.

We will also need to act together. The 2030 Agenda explicitly aims to get government, multilateral, civil society and private sector stakeholders working in concert. Goal 16 could draw the peacebuilding, justice, governance, and rights communities onto one platform, where these highly interdependent issues belong. Silos should be broken through the development of a holistic, shared vision of transformative change. A clear strategy and set of tangible actions driven by a group of influential Goal 16 champions could prove impactful. But acting together will also mean engaging well beyond the like-minded, including with the diplomatic and security actors who have an immense influence on our work.

Finally, we will need to act more coherently across three levels. First, support will be needed in countries furthest behind, critically those at risk of or experiencing conflict. Second, decisive collective action is required on transnational issues, such as illicit financial flows, as well as on common global challenges like shrinking civil society space. Third, the universality of the new development agenda must be taken seriously at home if we expect others to do the same and have a genuinely two-way exchange on different models of progress. This should go beyond symbolism, recognising that western societies are at risk of themselves becoming more closed, exclusionary and conflicted; Innovative approaches to cooperation that work at the intersection of bilateral, global and domestic policy-making will become increasingly more relevant than the donor-recipient frameworks of today.

About the author: Thomas Wheeler is a Conflict and Security Adviser on Saferworld's Policy Programme where he leads on global conflict prevention policy. His current focus is on the implementation and monitoring of the 2030 Agenda, the New Deal for engagement in fragile states, and transnational stresses. He previously worked on Saferworld's China and Africa programmes. Thomas holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

Other recent indicators of positive peace are worrying: One 2010 study suggests that even the 20 fastest reforming ‘fragile’ states would still take 41 years to reach an average score on the World Bank’s rule of law indicator. Over the past 10 years, 105 countries have seen a net decline in democracy as measured by Freedom House; only 61 have experienced a net improvement. Major protests have occurred around the world with increasing frequency since the second half of the 2000s. As for fundamental freedoms, more than 60 countries have passed or drafted laws that curtail the activity of civil society in the last three years while two-thirds of the 180 countries surveyed for the 2015 World Press Freedom Index performed less well than in the previous year. Overall, taking a broad view of positive peace over the past eight years, the Global Peace Index has documented small but significant declines.

It is debatable whether the momentum of the past 50 years or so is slowing or even reversing. Spikes in conflict deaths, challenges to democracy, or restrictions on freedoms are not necessarily representative of long-term future trends. Moreover, not all data sets point in the same direction (V-dem, for example, does not present as pessimistic a view on democracy as Freedom House) and we know that data can only tell an incomplete story. Either way, however, it is clear that making progress towards Goal 16 will not happen in the absence of concerted international action.

A glance at the global environment hardly installs confidence. To start with, we will increasingly face transnational issues that drive conflict, including illicit financial flows, arms transfers, the drugs trade, climate change and terrorism. On some of these issues the international community has failed to act, on others action has done more harm than good. Meanwhile international relations are uncertain and our systems of global governance are under immense strain, as the UN Security Council’s impasse on Syria tragically demonstrates. In the West, continued austerity risks discouraging attention to global development while the politics of fear encourages closed societies who build walls and the adoption of a narrow and short-sighed definition of the national interest.

Getting back on track

Resignation is one option. Another is to think about how the 2030 Agenda’s commitment to peace and Goal 16 can be used. Significant political capital was invested in getting agreement on the goal. This can now be spent on generating momentum for action well beyond New York. We can talk about root causes, but we ultimately know that progress on the issues contained in Goal 16 will come down to political leadership at domestic level within both state and society. Consensus within the development and peacebuilding community on the need to “work politically” risks becoming meaningless if interpreted as merely understanding local politics and working with the grain of the status quo. We should go further and use Goal 16 to channel international support to change-makers at national level, whether they are reformers in the ministry of justice, human rights defenders, or businesses intent on strengthening the rule of law. Working politically may mean taking sides, but 193 member states have signed up to the commitments and language of Goal 16, creating a legitimate basis for engagement across a host of contexts and with a range of actors.

With this in mind, it will be important to acknowledge that specific aspects of Goal 16 will be relevant to different actors in different contexts and at different junctures in time. This will mean working flexibly and avoiding the temptation to replicate template programming approaches from one context to another. And the 15 year time span of the SDGs means we can work to sensible long-term time horizons rather than merely hopping from one project to the next. In addition, we now have a means for tracking progress: the global SDG indicators are perfect, but they will generate new data on issues not traditionally tracked officially or in a way that is comparable between countries. This data will be the currency of accountability processes. The world will need to make significant investments in data gathering capacities, both within national statistical systems but also among multilateral agencies and civil society with the overall aim of creating pluralistic data ecosystems.

We will also need to act together. The 2030 Agenda explicitly aims to get government, multilateral, civil society and private sector stakeholders working in concert. Goal 16 could draw the peacebuilding, justice, governance, and rights communities onto one platform, where these highly interdependent issues belong. Silos should be broken through the development of a holistic, shared vision of transformative change. A clear strategy and set of tangible actions driven by a group of influential Goal 16 champions could prove impactful. But acting together will also mean engaging well beyond the like-minded, including with the diplomatic and security actors who have an immense influence on our work.

Finally, we will need to act more coherently across three levels. First, support will be needed in countries furthest behind, critically those at risk of or experiencing conflict. Second, decisive collective action is required on transnational issues, such as illicit financial flows, as well as on common global challenges like shrinking civil society space. Third, the universality of the new development agenda must be taken seriously at home if we expect others to do the same and have a genuinely two-way exchange on different models of progress. This should go beyond symbolism, recognising that western societies are at risk of themselves becoming more closed, exclusionary and conflicted; Innovative approaches to cooperation that work at the intersection of bilateral, global and domestic policy-making will become increasingly more relevant than the donor-recipient frameworks of today.

About the author: Thomas Wheeler is a Conflict and Security Adviser on Saferworld's Policy Programme where he leads on global conflict prevention policy. His current focus is on the implementation and monitoring of the 2030 Agenda, the New Deal for engagement in fragile states, and transnational stresses. He previously worked on Saferworld's China and Africa programmes. Thomas holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

Other recent indicators of positive peace are worrying: One 2010 study suggests that even the 20 fastest reforming ‘fragile’ states would still take 41 years to reach an average score on the World Bank’s rule of law indicator. Over the past 10 years, 105 countries have seen a net decline in democracy as measured by Freedom House; only 61 have experienced a net improvement. Major protests have occurred around the world with increasing frequency since the second half of the 2000s. As for fundamental freedoms, more than 60 countries have passed or drafted laws that curtail the activity of civil society in the last three years while two-thirds of the 180 countries surveyed for the 2015 World Press Freedom Index performed less well than in the previous year. Overall, taking a broad view of positive peace over the past eight years, the Global Peace Index has documented small but significant declines.

It is debatable whether the momentum of the past 50 years or so is slowing or even reversing. Spikes in conflict deaths, challenges to democracy, or restrictions on freedoms are not necessarily representative of long-term future trends. Moreover, not all data sets point in the same direction (V-dem, for example, does not present as pessimistic a view on democracy as Freedom House) and we know that data can only tell an incomplete story. Either way, however, it is clear that making progress towards Goal 16 will not happen in the absence of concerted international action.

A glance at the global environment hardly installs confidence. To start with, we will increasingly face transnational issues that drive conflict, including illicit financial flows, arms transfers, the drugs trade, climate change and terrorism. On some of these issues the international community has failed to act, on others action has done more harm than good. Meanwhile international relations are uncertain and our systems of global governance are under immense strain, as the UN Security Council’s impasse on Syria tragically demonstrates. In the West, continued austerity risks discouraging attention to global development while the politics of fear encourages closed societies who build walls and the adoption of a narrow and short-sighed definition of the national interest.

Getting back on track

Resignation is one option. Another is to think about how the 2030 Agenda’s commitment to peace and Goal 16 can be used. Significant political capital was invested in getting agreement on the goal. This can now be spent on generating momentum for action well beyond New York. We can talk about root causes, but we ultimately know that progress on the issues contained in Goal 16 will come down to political leadership at domestic level within both state and society. Consensus within the development and peacebuilding community on the need to “work politically” risks becoming meaningless if interpreted as merely understanding local politics and working with the grain of the status quo. We should go further and use Goal 16 to channel international support to change-makers at national level, whether they are reformers in the ministry of justice, human rights defenders, or businesses intent on strengthening the rule of law. Working politically may mean taking sides, but 193 member states have signed up to the commitments and language of Goal 16, creating a legitimate basis for engagement across a host of contexts and with a range of actors.

With this in mind, it will be important to acknowledge that specific aspects of Goal 16 will be relevant to different actors in different contexts and at different junctures in time. This will mean working flexibly and avoiding the temptation to replicate template programming approaches from one context to another. And the 15 year time span of the SDGs means we can work to sensible long-term time horizons rather than merely hopping from one project to the next. In addition, we now have a means for tracking progress: the global SDG indicators are perfect, but they will generate new data on issues not traditionally tracked officially or in a way that is comparable between countries. This data will be the currency of accountability processes. The world will need to make significant investments in data gathering capacities, both within national statistical systems but also among multilateral agencies and civil society with the overall aim of creating pluralistic data ecosystems.

We will also need to act together. The 2030 Agenda explicitly aims to get government, multilateral, civil society and private sector stakeholders working in concert. Goal 16 could draw the peacebuilding, justice, governance, and rights communities onto one platform, where these highly interdependent issues belong. Silos should be broken through the development of a holistic, shared vision of transformative change. A clear strategy and set of tangible actions driven by a group of influential Goal 16 champions could prove impactful. But acting together will also mean engaging well beyond the like-minded, including with the diplomatic and security actors who have an immense influence on our work.

Finally, we will need to act more coherently across three levels. First, support will be needed in countries furthest behind, critically those at risk of or experiencing conflict. Second, decisive collective action is required on transnational issues, such as illicit financial flows, as well as on common global challenges like shrinking civil society space. Third, the universality of the new development agenda must be taken seriously at home if we expect others to do the same and have a genuinely two-way exchange on different models of progress. This should go beyond symbolism, recognising that western societies are at risk of themselves becoming more closed, exclusionary and conflicted; Innovative approaches to cooperation that work at the intersection of bilateral, global and domestic policy-making will become increasingly more relevant than the donor-recipient frameworks of today.

About the author: Thomas Wheeler is a Conflict and Security Adviser on Saferworld's Policy Programme where he leads on global conflict prevention policy. His current focus is on the implementation and monitoring of the 2030 Agenda, the New Deal for engagement in fragile states, and transnational stresses. He previously worked on Saferworld's China and Africa programmes. Thomas holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

Other recent indicators of positive peace are worrying: One 2010 study suggests that even the 20 fastest reforming ‘fragile’ states would still take 41 years to reach an average score on the World Bank’s rule of law indicator. Over the past 10 years, 105 countries have seen a net decline in democracy as measured by Freedom House; only 61 have experienced a net improvement. Major protests have occurred around the world with increasing frequency since the second half of the 2000s. As for fundamental freedoms, more than 60 countries have passed or drafted laws that curtail the activity of civil society in the last three years while two-thirds of the 180 countries surveyed for the 2015 World Press Freedom Index performed less well than in the previous year. Overall, taking a broad view of positive peace over the past eight years, the Global Peace Index has documented small but significant declines.

It is debatable whether the momentum of the past 50 years or so is slowing or even reversing. Spikes in conflict deaths, challenges to democracy, or restrictions on freedoms are not necessarily representative of long-term future trends. Moreover, not all data sets point in the same direction (V-dem, for example, does not present as pessimistic a view on democracy as Freedom House) and we know that data can only tell an incomplete story. Either way, however, it is clear that making progress towards Goal 16 will not happen in the absence of concerted international action.

A glance at the global environment hardly installs confidence. To start with, we will increasingly face transnational issues that drive conflict, including illicit financial flows, arms transfers, the drugs trade, climate change and terrorism. On some of these issues the international community has failed to act, on others action has done more harm than good. Meanwhile international relations are uncertain and our systems of global governance are under immense strain, as the UN Security Council’s impasse on Syria tragically demonstrates. In the West, continued austerity risks discouraging attention to global development while the politics of fear encourages closed societies who build walls and the adoption of a narrow and short-sighed definition of the national interest.

Getting back on track

Resignation is one option. Another is to think about how the 2030 Agenda’s commitment to peace and Goal 16 can be used. Significant political capital was invested in getting agreement on the goal. This can now be spent on generating momentum for action well beyond New York. We can talk about root causes, but we ultimately know that progress on the issues contained in Goal 16 will come down to political leadership at domestic level within both state and society. Consensus within the development and peacebuilding community on the need to “work politically” risks becoming meaningless if interpreted as merely understanding local politics and working with the grain of the status quo. We should go further and use Goal 16 to channel international support to change-makers at national level, whether they are reformers in the ministry of justice, human rights defenders, or businesses intent on strengthening the rule of law. Working politically may mean taking sides, but 193 member states have signed up to the commitments and language of Goal 16, creating a legitimate basis for engagement across a host of contexts and with a range of actors.

With this in mind, it will be important to acknowledge that specific aspects of Goal 16 will be relevant to different actors in different contexts and at different junctures in time. This will mean working flexibly and avoiding the temptation to replicate template programming approaches from one context to another. And the 15 year time span of the SDGs means we can work to sensible long-term time horizons rather than merely hopping from one project to the next. In addition, we now have a means for tracking progress: the global SDG indicators are perfect, but they will generate new data on issues not traditionally tracked officially or in a way that is comparable between countries. This data will be the currency of accountability processes. The world will need to make significant investments in data gathering capacities, both within national statistical systems but also among multilateral agencies and civil society with the overall aim of creating pluralistic data ecosystems.

We will also need to act together. The 2030 Agenda explicitly aims to get government, multilateral, civil society and private sector stakeholders working in concert. Goal 16 could draw the peacebuilding, justice, governance, and rights communities onto one platform, where these highly interdependent issues belong. Silos should be broken through the development of a holistic, shared vision of transformative change. A clear strategy and set of tangible actions driven by a group of influential Goal 16 champions could prove impactful. But acting together will also mean engaging well beyond the like-minded, including with the diplomatic and security actors who have an immense influence on our work.

Finally, we will need to act more coherently across three levels. First, support will be needed in countries furthest behind, critically those at risk of or experiencing conflict. Second, decisive collective action is required on transnational issues, such as illicit financial flows, as well as on common global challenges like shrinking civil society space. Third, the universality of the new development agenda must be taken seriously at home if we expect others to do the same and have a genuinely two-way exchange on different models of progress. This should go beyond symbolism, recognising that western societies are at risk of themselves becoming more closed, exclusionary and conflicted; Innovative approaches to cooperation that work at the intersection of bilateral, global and domestic policy-making will become increasingly more relevant than the donor-recipient frameworks of today.

About the author: Thomas Wheeler is a Conflict and Security Adviser on Saferworld's Policy Programme where he leads on global conflict prevention policy. His current focus is on the implementation and monitoring of the 2030 Agenda, the New Deal for engagement in fragile states, and transnational stresses. He previously worked on Saferworld's China and Africa programmes. Thomas holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from the Department of War Studies, King's College London.The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.

a global affairs media network

Peace Has Been Made a Global Development Priority. Now What?

World map painted on hands isolated on white|

July 1, 2016

“We are determined to foster peaceful, just and inclusive societies which are free from fear and violence” states the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. At global level the normative debate on the linkages between peace and development has been won with the identification of peace as one of five cross cutting priorities in new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the inclusion of SDG 16 on peace, justice and accountable governance. But – already 2% of the way to 2030 - what do those working on the intersection between peace and development need to do next?

The past is just the prologue

We should first recognise that momentum is with us, with regards to both reductions in violence and the factors underpinning positive peace. Peaking in the late 1980s and early 90s, the number of armed conflicts has fallen significantly. The risk of inter-state war – and the levels of carnage seen in two world wars – has also declined. While stubbornly high in some contexts, homicide rates have fallen. Measures of access to justice by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) initiative show progress for both men and women over the last 50 years. The number of democracies increased from 30 in 1959 to 87 in 2009. We have also seen a significant expansion in measures of freedoms of expression in the same period.

We must, nonetheless, be sober about the scale of the challenge ahead. We met the target of halving extreme poverty in the MDG period but the SDGs aim to now end extreme poverty. Those living in extreme poverty will increasingly be concentrated in countries experiencing or at risk of conflict. Worryingly, the number of conflicts jumped from a low of five in 2010 to 11 in 2014, the most deadly year in the past 20. Syria accounts for many of these deaths, but of “the ten conflicts with the most fatalities in 2013, eight became more violent in 2014.” Using 2014 as our baseline year, we will not get back down to 2010 levels by 2030 even with a 75% reduction in conflict deaths.

Other recent indicators of positive peace are worrying: One 2010 study suggests that even the 20 fastest reforming ‘fragile’ states would still take 41 years to reach an average score on the World Bank’s rule of law indicator. Over the past 10 years, 105 countries have seen a net decline in democracy as measured by Freedom House; only 61 have experienced a net improvement. Major protests have occurred around the world with increasing frequency since the second half of the 2000s. As for fundamental freedoms, more than 60 countries have passed or drafted laws that curtail the activity of civil society in the last three years while two-thirds of the 180 countries surveyed for the 2015 World Press Freedom Index performed less well than in the previous year. Overall, taking a broad view of positive peace over the past eight years, the Global Peace Index has documented small but significant declines.

It is debatable whether the momentum of the past 50 years or so is slowing or even reversing. Spikes in conflict deaths, challenges to democracy, or restrictions on freedoms are not necessarily representative of long-term future trends. Moreover, not all data sets point in the same direction (V-dem, for example, does not present as pessimistic a view on democracy as Freedom House) and we know that data can only tell an incomplete story. Either way, however, it is clear that making progress towards Goal 16 will not happen in the absence of concerted international action.

A glance at the global environment hardly installs confidence. To start with, we will increasingly face transnational issues that drive conflict, including illicit financial flows, arms transfers, the drugs trade, climate change and terrorism. On some of these issues the international community has failed to act, on others action has done more harm than good. Meanwhile international relations are uncertain and our systems of global governance are under immense strain, as the UN Security Council’s impasse on Syria tragically demonstrates. In the West, continued austerity risks discouraging attention to global development while the politics of fear encourages closed societies who build walls and the adoption of a narrow and short-sighed definition of the national interest.

Getting back on track

Resignation is one option. Another is to think about how the 2030 Agenda’s commitment to peace and Goal 16 can be used. Significant political capital was invested in getting agreement on the goal. This can now be spent on generating momentum for action well beyond New York. We can talk about root causes, but we ultimately know that progress on the issues contained in Goal 16 will come down to political leadership at domestic level within both state and society. Consensus within the development and peacebuilding community on the need to “work politically” risks becoming meaningless if interpreted as merely understanding local politics and working with the grain of the status quo. We should go further and use Goal 16 to channel international support to change-makers at national level, whether they are reformers in the ministry of justice, human rights defenders, or businesses intent on strengthening the rule of law. Working politically may mean taking sides, but 193 member states have signed up to the commitments and language of Goal 16, creating a legitimate basis for engagement across a host of contexts and with a range of actors.

With this in mind, it will be important to acknowledge that specific aspects of Goal 16 will be relevant to different actors in different contexts and at different junctures in time. This will mean working flexibly and avoiding the temptation to replicate template programming approaches from one context to another. And the 15 year time span of the SDGs means we can work to sensible long-term time horizons rather than merely hopping from one project to the next. In addition, we now have a means for tracking progress: the global SDG indicators are perfect, but they will generate new data on issues not traditionally tracked officially or in a way that is comparable between countries. This data will be the currency of accountability processes. The world will need to make significant investments in data gathering capacities, both within national statistical systems but also among multilateral agencies and civil society with the overall aim of creating pluralistic data ecosystems.

We will also need to act together. The 2030 Agenda explicitly aims to get government, multilateral, civil society and private sector stakeholders working in concert. Goal 16 could draw the peacebuilding, justice, governance, and rights communities onto one platform, where these highly interdependent issues belong. Silos should be broken through the development of a holistic, shared vision of transformative change. A clear strategy and set of tangible actions driven by a group of influential Goal 16 champions could prove impactful. But acting together will also mean engaging well beyond the like-minded, including with the diplomatic and security actors who have an immense influence on our work.

Finally, we will need to act more coherently across three levels. First, support will be needed in countries furthest behind, critically those at risk of or experiencing conflict. Second, decisive collective action is required on transnational issues, such as illicit financial flows, as well as on common global challenges like shrinking civil society space. Third, the universality of the new development agenda must be taken seriously at home if we expect others to do the same and have a genuinely two-way exchange on different models of progress. This should go beyond symbolism, recognising that western societies are at risk of themselves becoming more closed, exclusionary and conflicted; Innovative approaches to cooperation that work at the intersection of bilateral, global and domestic policy-making will become increasingly more relevant than the donor-recipient frameworks of today.

About the author: Thomas Wheeler is a Conflict and Security Adviser on Saferworld's Policy Programme where he leads on global conflict prevention policy. His current focus is on the implementation and monitoring of the 2030 Agenda, the New Deal for engagement in fragile states, and transnational stresses. He previously worked on Saferworld's China and Africa programmes. Thomas holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

Other recent indicators of positive peace are worrying: One 2010 study suggests that even the 20 fastest reforming ‘fragile’ states would still take 41 years to reach an average score on the World Bank’s rule of law indicator. Over the past 10 years, 105 countries have seen a net decline in democracy as measured by Freedom House; only 61 have experienced a net improvement. Major protests have occurred around the world with increasing frequency since the second half of the 2000s. As for fundamental freedoms, more than 60 countries have passed or drafted laws that curtail the activity of civil society in the last three years while two-thirds of the 180 countries surveyed for the 2015 World Press Freedom Index performed less well than in the previous year. Overall, taking a broad view of positive peace over the past eight years, the Global Peace Index has documented small but significant declines.

It is debatable whether the momentum of the past 50 years or so is slowing or even reversing. Spikes in conflict deaths, challenges to democracy, or restrictions on freedoms are not necessarily representative of long-term future trends. Moreover, not all data sets point in the same direction (V-dem, for example, does not present as pessimistic a view on democracy as Freedom House) and we know that data can only tell an incomplete story. Either way, however, it is clear that making progress towards Goal 16 will not happen in the absence of concerted international action.

A glance at the global environment hardly installs confidence. To start with, we will increasingly face transnational issues that drive conflict, including illicit financial flows, arms transfers, the drugs trade, climate change and terrorism. On some of these issues the international community has failed to act, on others action has done more harm than good. Meanwhile international relations are uncertain and our systems of global governance are under immense strain, as the UN Security Council’s impasse on Syria tragically demonstrates. In the West, continued austerity risks discouraging attention to global development while the politics of fear encourages closed societies who build walls and the adoption of a narrow and short-sighed definition of the national interest.

Getting back on track

Resignation is one option. Another is to think about how the 2030 Agenda’s commitment to peace and Goal 16 can be used. Significant political capital was invested in getting agreement on the goal. This can now be spent on generating momentum for action well beyond New York. We can talk about root causes, but we ultimately know that progress on the issues contained in Goal 16 will come down to political leadership at domestic level within both state and society. Consensus within the development and peacebuilding community on the need to “work politically” risks becoming meaningless if interpreted as merely understanding local politics and working with the grain of the status quo. We should go further and use Goal 16 to channel international support to change-makers at national level, whether they are reformers in the ministry of justice, human rights defenders, or businesses intent on strengthening the rule of law. Working politically may mean taking sides, but 193 member states have signed up to the commitments and language of Goal 16, creating a legitimate basis for engagement across a host of contexts and with a range of actors.

With this in mind, it will be important to acknowledge that specific aspects of Goal 16 will be relevant to different actors in different contexts and at different junctures in time. This will mean working flexibly and avoiding the temptation to replicate template programming approaches from one context to another. And the 15 year time span of the SDGs means we can work to sensible long-term time horizons rather than merely hopping from one project to the next. In addition, we now have a means for tracking progress: the global SDG indicators are perfect, but they will generate new data on issues not traditionally tracked officially or in a way that is comparable between countries. This data will be the currency of accountability processes. The world will need to make significant investments in data gathering capacities, both within national statistical systems but also among multilateral agencies and civil society with the overall aim of creating pluralistic data ecosystems.

We will also need to act together. The 2030 Agenda explicitly aims to get government, multilateral, civil society and private sector stakeholders working in concert. Goal 16 could draw the peacebuilding, justice, governance, and rights communities onto one platform, where these highly interdependent issues belong. Silos should be broken through the development of a holistic, shared vision of transformative change. A clear strategy and set of tangible actions driven by a group of influential Goal 16 champions could prove impactful. But acting together will also mean engaging well beyond the like-minded, including with the diplomatic and security actors who have an immense influence on our work.

Finally, we will need to act more coherently across three levels. First, support will be needed in countries furthest behind, critically those at risk of or experiencing conflict. Second, decisive collective action is required on transnational issues, such as illicit financial flows, as well as on common global challenges like shrinking civil society space. Third, the universality of the new development agenda must be taken seriously at home if we expect others to do the same and have a genuinely two-way exchange on different models of progress. This should go beyond symbolism, recognising that western societies are at risk of themselves becoming more closed, exclusionary and conflicted; Innovative approaches to cooperation that work at the intersection of bilateral, global and domestic policy-making will become increasingly more relevant than the donor-recipient frameworks of today.

About the author: Thomas Wheeler is a Conflict and Security Adviser on Saferworld's Policy Programme where he leads on global conflict prevention policy. His current focus is on the implementation and monitoring of the 2030 Agenda, the New Deal for engagement in fragile states, and transnational stresses. He previously worked on Saferworld's China and Africa programmes. Thomas holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

Other recent indicators of positive peace are worrying: One 2010 study suggests that even the 20 fastest reforming ‘fragile’ states would still take 41 years to reach an average score on the World Bank’s rule of law indicator. Over the past 10 years, 105 countries have seen a net decline in democracy as measured by Freedom House; only 61 have experienced a net improvement. Major protests have occurred around the world with increasing frequency since the second half of the 2000s. As for fundamental freedoms, more than 60 countries have passed or drafted laws that curtail the activity of civil society in the last three years while two-thirds of the 180 countries surveyed for the 2015 World Press Freedom Index performed less well than in the previous year. Overall, taking a broad view of positive peace over the past eight years, the Global Peace Index has documented small but significant declines.

It is debatable whether the momentum of the past 50 years or so is slowing or even reversing. Spikes in conflict deaths, challenges to democracy, or restrictions on freedoms are not necessarily representative of long-term future trends. Moreover, not all data sets point in the same direction (V-dem, for example, does not present as pessimistic a view on democracy as Freedom House) and we know that data can only tell an incomplete story. Either way, however, it is clear that making progress towards Goal 16 will not happen in the absence of concerted international action.

A glance at the global environment hardly installs confidence. To start with, we will increasingly face transnational issues that drive conflict, including illicit financial flows, arms transfers, the drugs trade, climate change and terrorism. On some of these issues the international community has failed to act, on others action has done more harm than good. Meanwhile international relations are uncertain and our systems of global governance are under immense strain, as the UN Security Council’s impasse on Syria tragically demonstrates. In the West, continued austerity risks discouraging attention to global development while the politics of fear encourages closed societies who build walls and the adoption of a narrow and short-sighed definition of the national interest.

Getting back on track

Resignation is one option. Another is to think about how the 2030 Agenda’s commitment to peace and Goal 16 can be used. Significant political capital was invested in getting agreement on the goal. This can now be spent on generating momentum for action well beyond New York. We can talk about root causes, but we ultimately know that progress on the issues contained in Goal 16 will come down to political leadership at domestic level within both state and society. Consensus within the development and peacebuilding community on the need to “work politically” risks becoming meaningless if interpreted as merely understanding local politics and working with the grain of the status quo. We should go further and use Goal 16 to channel international support to change-makers at national level, whether they are reformers in the ministry of justice, human rights defenders, or businesses intent on strengthening the rule of law. Working politically may mean taking sides, but 193 member states have signed up to the commitments and language of Goal 16, creating a legitimate basis for engagement across a host of contexts and with a range of actors.

With this in mind, it will be important to acknowledge that specific aspects of Goal 16 will be relevant to different actors in different contexts and at different junctures in time. This will mean working flexibly and avoiding the temptation to replicate template programming approaches from one context to another. And the 15 year time span of the SDGs means we can work to sensible long-term time horizons rather than merely hopping from one project to the next. In addition, we now have a means for tracking progress: the global SDG indicators are perfect, but they will generate new data on issues not traditionally tracked officially or in a way that is comparable between countries. This data will be the currency of accountability processes. The world will need to make significant investments in data gathering capacities, both within national statistical systems but also among multilateral agencies and civil society with the overall aim of creating pluralistic data ecosystems.

We will also need to act together. The 2030 Agenda explicitly aims to get government, multilateral, civil society and private sector stakeholders working in concert. Goal 16 could draw the peacebuilding, justice, governance, and rights communities onto one platform, where these highly interdependent issues belong. Silos should be broken through the development of a holistic, shared vision of transformative change. A clear strategy and set of tangible actions driven by a group of influential Goal 16 champions could prove impactful. But acting together will also mean engaging well beyond the like-minded, including with the diplomatic and security actors who have an immense influence on our work.

Finally, we will need to act more coherently across three levels. First, support will be needed in countries furthest behind, critically those at risk of or experiencing conflict. Second, decisive collective action is required on transnational issues, such as illicit financial flows, as well as on common global challenges like shrinking civil society space. Third, the universality of the new development agenda must be taken seriously at home if we expect others to do the same and have a genuinely two-way exchange on different models of progress. This should go beyond symbolism, recognising that western societies are at risk of themselves becoming more closed, exclusionary and conflicted; Innovative approaches to cooperation that work at the intersection of bilateral, global and domestic policy-making will become increasingly more relevant than the donor-recipient frameworks of today.

About the author: Thomas Wheeler is a Conflict and Security Adviser on Saferworld's Policy Programme where he leads on global conflict prevention policy. His current focus is on the implementation and monitoring of the 2030 Agenda, the New Deal for engagement in fragile states, and transnational stresses. He previously worked on Saferworld's China and Africa programmes. Thomas holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

Other recent indicators of positive peace are worrying: One 2010 study suggests that even the 20 fastest reforming ‘fragile’ states would still take 41 years to reach an average score on the World Bank’s rule of law indicator. Over the past 10 years, 105 countries have seen a net decline in democracy as measured by Freedom House; only 61 have experienced a net improvement. Major protests have occurred around the world with increasing frequency since the second half of the 2000s. As for fundamental freedoms, more than 60 countries have passed or drafted laws that curtail the activity of civil society in the last three years while two-thirds of the 180 countries surveyed for the 2015 World Press Freedom Index performed less well than in the previous year. Overall, taking a broad view of positive peace over the past eight years, the Global Peace Index has documented small but significant declines.

It is debatable whether the momentum of the past 50 years or so is slowing or even reversing. Spikes in conflict deaths, challenges to democracy, or restrictions on freedoms are not necessarily representative of long-term future trends. Moreover, not all data sets point in the same direction (V-dem, for example, does not present as pessimistic a view on democracy as Freedom House) and we know that data can only tell an incomplete story. Either way, however, it is clear that making progress towards Goal 16 will not happen in the absence of concerted international action.

A glance at the global environment hardly installs confidence. To start with, we will increasingly face transnational issues that drive conflict, including illicit financial flows, arms transfers, the drugs trade, climate change and terrorism. On some of these issues the international community has failed to act, on others action has done more harm than good. Meanwhile international relations are uncertain and our systems of global governance are under immense strain, as the UN Security Council’s impasse on Syria tragically demonstrates. In the West, continued austerity risks discouraging attention to global development while the politics of fear encourages closed societies who build walls and the adoption of a narrow and short-sighed definition of the national interest.

Getting back on track

Resignation is one option. Another is to think about how the 2030 Agenda’s commitment to peace and Goal 16 can be used. Significant political capital was invested in getting agreement on the goal. This can now be spent on generating momentum for action well beyond New York. We can talk about root causes, but we ultimately know that progress on the issues contained in Goal 16 will come down to political leadership at domestic level within both state and society. Consensus within the development and peacebuilding community on the need to “work politically” risks becoming meaningless if interpreted as merely understanding local politics and working with the grain of the status quo. We should go further and use Goal 16 to channel international support to change-makers at national level, whether they are reformers in the ministry of justice, human rights defenders, or businesses intent on strengthening the rule of law. Working politically may mean taking sides, but 193 member states have signed up to the commitments and language of Goal 16, creating a legitimate basis for engagement across a host of contexts and with a range of actors.

With this in mind, it will be important to acknowledge that specific aspects of Goal 16 will be relevant to different actors in different contexts and at different junctures in time. This will mean working flexibly and avoiding the temptation to replicate template programming approaches from one context to another. And the 15 year time span of the SDGs means we can work to sensible long-term time horizons rather than merely hopping from one project to the next. In addition, we now have a means for tracking progress: the global SDG indicators are perfect, but they will generate new data on issues not traditionally tracked officially or in a way that is comparable between countries. This data will be the currency of accountability processes. The world will need to make significant investments in data gathering capacities, both within national statistical systems but also among multilateral agencies and civil society with the overall aim of creating pluralistic data ecosystems.

We will also need to act together. The 2030 Agenda explicitly aims to get government, multilateral, civil society and private sector stakeholders working in concert. Goal 16 could draw the peacebuilding, justice, governance, and rights communities onto one platform, where these highly interdependent issues belong. Silos should be broken through the development of a holistic, shared vision of transformative change. A clear strategy and set of tangible actions driven by a group of influential Goal 16 champions could prove impactful. But acting together will also mean engaging well beyond the like-minded, including with the diplomatic and security actors who have an immense influence on our work.

Finally, we will need to act more coherently across three levels. First, support will be needed in countries furthest behind, critically those at risk of or experiencing conflict. Second, decisive collective action is required on transnational issues, such as illicit financial flows, as well as on common global challenges like shrinking civil society space. Third, the universality of the new development agenda must be taken seriously at home if we expect others to do the same and have a genuinely two-way exchange on different models of progress. This should go beyond symbolism, recognising that western societies are at risk of themselves becoming more closed, exclusionary and conflicted; Innovative approaches to cooperation that work at the intersection of bilateral, global and domestic policy-making will become increasingly more relevant than the donor-recipient frameworks of today.

About the author: Thomas Wheeler is a Conflict and Security Adviser on Saferworld's Policy Programme where he leads on global conflict prevention policy. His current focus is on the implementation and monitoring of the 2030 Agenda, the New Deal for engagement in fragile states, and transnational stresses. He previously worked on Saferworld's China and Africa programmes. Thomas holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from the Department of War Studies, King's College London.The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.