China is undergoing a revolution in the realm of IP and innovation. In just 3 decades, China has gone from no IP law to leading the world in patents filed and litigation to enforce patents. The level of innovation in China may well be the next big surprise for many in the West.

“Open innovation” is often used to describe collaboration with outside partners to accelerate innovation. Dialog about open innovation frequently assumes that it is recent and Western, but successful open innovation is not unique to the West. Innovation via cooperation between unlikely partners has been a characteristic of China for centuries. Relevant terms are guanxi (often translated as “relationships”) and yuanfen (fate that brings partners together). In China, guanxi and yuanfen have allowed proximity and chance to bring business partners together when there was a basis of trust, resulting in innovative alliances. The fusion of skillsets in China’s manufacturing economy often stems from collaborative innovation, though the results are often decried as merely the machinery of copying.

Accelerated innovation in China, including advanced systems for responding to market feedback, is the subject of a report from the MIT Sloan Management Review, where Peter Williamson and Eden Yin survey China’s innovation in rapid manufacturing and parallel engineering. A key element is obtaining feedback and innovation concepts from outside partners or customers. The cited example of Mindray Medical International, China’s largest medical equipment maker, shows how R&D fueled by rapid response to outside feedback enables advanced new products to launch four times as fast as foreign competitors. This is not old-school copying, but the impressive fruit of aggressive open innovation.

Many more examples could be cited, such as Lenovo’s rapid acquisition of foreign patents to fuel entry into new areas, or Wuxi Pharma Tech (NYSE: WX) and their collaboration with Germany’s Targos Molecular Pathology to support WuXi's bioanalytical work for pharmaceutical customers.

The global IP community was surprised in 2014 to learn that a Chinese paper company had secured 8 billion RMB in funding (over US$1 billion) backed by its intellectual property. The story was reported in a Chinese paper-industry publication in March 2014, and a few days later we had the privilege of reporting this story to the Western world on the Innovation Fatigue blog, which was in turn quickly picked up by Intellectual Asset Management (IAM) magazine. IAM’s blog noted that this deal is one of the biggest IP-backed loans in history.

The company, Tralin Paper (Quanlin in Chinese, or Tranlin in recent U.S. stories), has a modest portfolio with around 100 Chinese patents, several internationally-filed patents and a few trademarks. Their technical strength is in creating paper with natural characteristics from waste paper and straw. Even if guanxi rather than IP was behind the financing, the fact that IP was used as publicized basis for the deal underscores the increasing importance of IP in China and the diverse ways in which Chinese IP can generate value. For Tralin, even if the IP were window dressing, its role even as a prop at a minimum provided PR value and strengthened Tralin’s position as thought leader in its niche. The most reasonable assumption is that IP also provided direct financial benefits, not just window dressing.

In the U.S., where Chinese innovation and IP is often deprecated, the impact of this deal is being felt strongly as Tralin/Tranlin is investing $2 billion in Virginia and creating 2,000 jobs with the technology they are bringing to U.S. shores. News stories so far have missed the connection between U.S. jobs and Tranlin’s ability to get capital based on Chinese IP, but we hope that Americans might recognize that innovation and IP from China is at least partly responsible for this welcome job growth.

Tralin/Tranlin’s story is part of a landscape in China where entrepreneurs and creative leaders are discovering the many positive uses of IP, including its ability to secure capital and build partnerships. But many Western companies wishing to build partnerships with their technology fear China and the risk of misappropriated IP. This lack of trust is being addressed gradually as China strengthens its IP laws and IP enforcement systems. Lawsuits, no matter how fair, are a last resort. Successful joint innovation requires trust directly between parties, and both sides need more successful examples for inspiration. Fortunately, a powerful role model of the technical, cultural, and political bridge-building that can occur in a healthy relationship rooted in carefully-maintained trust can be seen in a remarkable experiment in technology transfer and international cooperation: the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership.

In Jinshan, China, a heavily populated district of Shanghai, composting was previously the only option for managing dairy waste. Unfortunately, the traditional way of letting manure decompose in the sun resulted in the release of unpleasant odor, the greenhouse gas methane, and manure-tainted runoff water into rivers. The situation in Jinshan is improving with the help of advanced anaerobic digesters designed by a U.S. professor at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Utah. Using this technology, pollution and solid waste were reduced by nearly half as 10,000 gallons/day of manure-rich slurry is treated. For the Jinshan Clean Energy Project, IP from the U.S. has been successfully transferred and adapted for use in China to solve a substantial environmental problem.

This invention addresses significant problems in the biogas field. The biogas coming from animal waste is methane contaminated with corrosive hydrogen sulfide and water vapor that needs to be removed before it can be used as a fuel. Biogas conditioners on the market may cost over $500,000. However, with the system patented by BYU professors, a conditioner can clean up biogas for one-eighth of the cost. The clean gas can be compressed for use in power generators and engines or converted to liquid biodiesel. Hansen's technology was brought to China in partnership with a Utah affiliated company and UQEP.

Meanwhile in the Western Chinese province of Qinghai, UQEP’s work includes initiatives to deal with heavy metals in water, capture of CO2, soil remediation, and clean up hazardous waste sites. These projects involve collaboration between China and a growing cluster of U.S. green tech companies such as Metallosensors. Partnership models similar to the Jinshan project are applied to solve further environmental challenges in China.

Metallosensors, for example, deals with heavy metals such as mercury, with innovative cost-effective and rapid methods to detect those pollutants. Since the waterways in Qinghai Province are important sources of water for China and Asia, reducing pollution in Qinghai is vitally important for the region. Utah Science Technology and Research (USTAR) professor Ling Zang from University of Utah is behind the mercury detection technology being commercialized by Metallosensors. This technology will be used to help manage heavy metals in Qinghai and elsewhere. The joint IP project between Metallosensors and UQEP involves licensing and respecting Metallosensors’ intellectual property, while effectively dealing with Chinese policy on IP and local funding.

The soil remediation project mentioned above involves technology from the University of Utah that is removing pollutants in the soil near the city of Wuxi (population 5 million) on the shores of Lake Taihu, which suffered devastating toxic algae blooms in 2007, linked to industrial pollutants. The situation in Wuxi presented an opportunity for collaboration between the Utah clean technology industry and a UQEP affiliated local partner in Shanghai. This local partner proposed a pilot demonstration project aimed at soil remediation in Wuxi. Using “heightened ozonation treatment” or HOT, developed by a professor at the University of Utah, UQEP’s Shanghai affiliated company would engineer a small-scale plant near Taihu Lake aimed at testing the remediation process on some of the soil on a plot formerly occupied by chemical industry factories. The project would require pioneering a new model for U.S.-China joint collaboration, IP protection, technology transfer, and policy implementation. The success of the project would provide a blueprint for future U.S.-China efforts in environmental clean technology that would pave the way for UQEP.

UQEP is a non-profit organization jointly supported by the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the Chinese National Development and Reform Commission. UQEP is "dedicated to building relationships, protecting intellectual property, and developing green technologies." The EcoPartnership between the State of Utah and the province of Qinghai draws upon similarities between the two. Both are western regions in their nations with high mountains, salt lakes and diverse cultures.

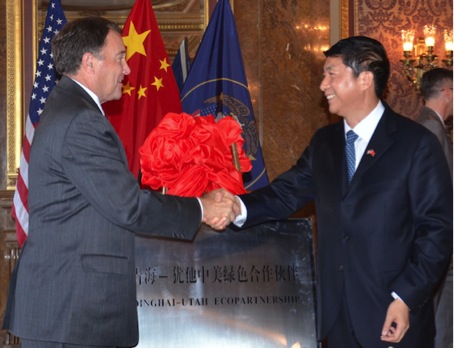

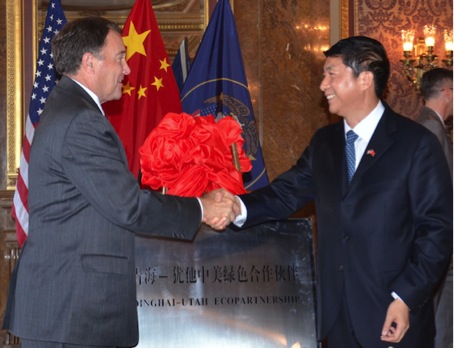

Inspired by these common elements, then Governor of Qinghai Province, Luo Huining, and Utah Governor Gary Herbert, developed a partnership aimed at joint innovation for environmental sustainability.

Inspired by these common elements, then Governor of Qinghai Province, Luo Huining, and Utah Governor Gary Herbert, developed a partnership aimed at joint innovation for environmental sustainability.

Though UQEP was launched in 2011, its foundation began earlier with bonds of trust developed between Utah government leaders, businesses, and universities with partners in China. In 2009, a Chinese UQEP-affiliated company, Honde, was established as an environmental technology company in partnership with the Utah government, universities, and clean technology businesses. One of its aims was to develop Utah-China relationships to set the stage for future collaboration and innovation. Honde’s mission was envisioned by Shawn Hu, a Chinese national who for over a decade worked as the Trade Representative for the state of Utah in China. Mr. Hu envisioned a collaborative trust platform emphasizing IP protection while promoting technology transfer and joint-research. With support from Utah government, the collaborative platform evolved into UQEP and in 2011 it was inducted into the EcoPartnership program.

UQEP is one of thirty-two EcoPartnerships and is the only state-province level EcoPartnership. It reaches far deeper than the state-province relationship with additional partnerships including cities, districts, universities, and local businesses. Generally, EcoPartnerships promote clean air, water, or transportation; clean, electricity; conservation of forests and wetlands. In July 2014 during the 6th round of the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue in Beijing, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry described the role of the EcoPartnership program as one of ”harnessing the ingenuity and the innovation of the private sector, universities, civil society, in order to promote economic growth, energy security, and environmental sustainability.” Qinghai province has already invested several million RMB in UQEP projects, and other government bodies in China are also active supporters. UQEP also collaborates with Purdue University scientists, thanks to the Purdue-led Eco-Partnership for Environmental Sustainability. One example of the benefits from joint efforts with Purdue is a project begun in 2014 aimed at improving water quality in Qinghai using advanced versions of a "slow sand filtration" system developed by Purdue's Chad Jahvert, professor of environmental engineering. The purification system is based on readily available resources and natural aerobic processes to break down pollutants in water. This technology transfer effort has already resulted in improved water quality for several families in Qinghai’s Dongshan township, where drinking water had largely come from untreated, turbid rainwater collected in cellars.

While the EcoPartnership brings obvious benefits to China as it gains access to technology and expertise to solve environmental problems, the benefits for the U.S. partners are also noteworthy. For Utah, the EcoPartnership:

- • Opens new markets for green technologies;

- • Provides large-scale cost effective testing of R&D concepts;

- • Increases cultural understanding by creating international fellowship opportunities for U.S. students and professionals;

- • Provides Utah businesses with a leadership edge in environmental technology through collaborating with China;

- • Gives U.S. partners early access to relevant research results from Chinese teams;

A lesson from the UQEP projects has been the importance of trust as a foundation for collaboration. This involves far more than lawyers and contracts.

Many Westerners have heard of guanxi. What is often missed is that guanxi is more than merely knowing others. Most importantly, it refers to relationships of trust that can take years to cultivate and involve effort to maintain. Trust is tied to reputation, and above all, UQEP's success came from a carefully earned reputation, especially that of Honde and the leaders behind UQEP. It took years of reputation building to reach the point where political barriers could be gently but vigorously moved aside to achieve mutual good in an experiment that is actively advancing China's environmental situation, Utah's commercialization of technology, and U.S.-China relations.

UQEP's experience also shows that trust is best established through face-to-face exchanges and incremental agreements leading to action.

Another important lesson taught by Honde's founder, Shawn Hu, is that doing business in China requires extreme patience followed by quick and efficient action. Building trust and gaining support for complex and sensitive projects with local and national governments can take years of navigating complex systems, but when the window of opportunity comes, rapid progress with demonstrated success is required. Thus, Honde carefully chose both the timing and the location of its projects to achieve success. This route creates momentum for future projects.

UQEP's story also points to the importance placed on IP respect. Many U.S. entities fear bringing their IP to China. One interesting approach to overcoming these fears was taken by Honde for the Wuxi project, wherein Honde licensed HOT technology, signing confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements, and requiring the same of local partners in Wuxi. Honde closely monitors the design, manufacture, and operation of HOT equipment and holds IP training sessions to establish a culture of IP respect. This culture has also been shared and emphasized during exchanges with local Chinese government leaders who have acknowledged the importance of protecting IP in order to continue doing business with U.S. companies.

As one of many indications of the significant government support UQEP is enjoying, a document signed by the governor of Qinghai Province makes the following declaration:

“…In order to assist the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership in successfully achieving their goals, all functioning departments and major cities are required to proactively support the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership by enhancing organization and coordination, creating a better atmosphere for cooperation and development, further encouraging cooperation in additional areas, and by specifically including the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership in individual action plans…”

Building the foundation of trust has taken years of patience and education. Chinese and American partners have both had substantial misapprehensions to overcome. UQEP's leaders and supporters have learned, though, that barriers can be circumnavigated with a combination of patience and swift action when the time is right.

There are also differences in perspectives regarding time and timing. The Chinese often feel that there is no permanency and thus questionable reliability on the U.S. side, for they see leadership changing all the time, with policies and funding rapidly shifting vacillating. Further, there is inherent distrust of outsiders on both sides. To deal with such challenges, UQEP relies on a platform that starts with academia and then brings in business and government as they look for a suitable joint project to build trust. When the timing is right, an opportunity may be pursued swiftly even if the project is not a perfect match.

UQEP has learned that fostering trust involves many meetings. Shawn Hu participated in over 60 meetings with various Chinese leaders to coordinate the Jinshan biogas project. Foreigners may not be used to this level of background work, but this is an important part of the local process in developing trust. The Chinese way is that if they like the project and the people, they will take risks to move ahead in spite of uncertainty. In this way, projects can swiftly cut through normal slow routes. This is part of an increasingly fast-paced culture in China that is often challenging for foreigners to understand or follow. When the timing is right and the foundations in place, the pace of innovation in China can surprise Western partners.

The power of open innovation is best tapped when there is a foundation of trust between partners, coupled with IP that can be used to meet compelling needs. The Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership is an excellent example of international open innovation that overcomes cultural and political boundaries, brings significant mutual benefit, and solves environmental problems. It also defies old stereotypes and demonstrates China’s coming of age in terms of IP respect. The foundation laid by UQEP can be expected to influence many future collaborative efforts in other areas.

Jeffrey D. Lindsay is Head of Intellectual Property at Asia Pulp & Paper in Shanghai. Edgar Gomez is a business consultant, researcher, and photographer. Alan Taylor Smurthwaite currently serves as the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership Intellectual Property and Innovation Coordinator managing environmental sustainability initiatives in Qinghai Province.

Second photo: Clean energy biogas facility in the Jinshan district of Shanghai, China. Courtesy of UQEP.

Third photo: Utah Governor Gary Herbert and the then Governor of Qinghhai province Luo Huining at the launching ceremony in Salt Lake City of the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership. Photo by David Monson.

This article was originally published in the Diplomatic Courier's November/December 2014 print edition.

a global affairs media network

Open Innovation and IP Trends in China: Insights from the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership

December 8, 2014

China is undergoing a revolution in the realm of IP and innovation. In just 3 decades, China has gone from no IP law to leading the world in patents filed and litigation to enforce patents. The level of innovation in China may well be the next big surprise for many in the West.

“Open innovation” is often used to describe collaboration with outside partners to accelerate innovation. Dialog about open innovation frequently assumes that it is recent and Western, but successful open innovation is not unique to the West. Innovation via cooperation between unlikely partners has been a characteristic of China for centuries. Relevant terms are guanxi (often translated as “relationships”) and yuanfen (fate that brings partners together). In China, guanxi and yuanfen have allowed proximity and chance to bring business partners together when there was a basis of trust, resulting in innovative alliances. The fusion of skillsets in China’s manufacturing economy often stems from collaborative innovation, though the results are often decried as merely the machinery of copying.

Accelerated innovation in China, including advanced systems for responding to market feedback, is the subject of a report from the MIT Sloan Management Review, where Peter Williamson and Eden Yin survey China’s innovation in rapid manufacturing and parallel engineering. A key element is obtaining feedback and innovation concepts from outside partners or customers. The cited example of Mindray Medical International, China’s largest medical equipment maker, shows how R&D fueled by rapid response to outside feedback enables advanced new products to launch four times as fast as foreign competitors. This is not old-school copying, but the impressive fruit of aggressive open innovation.

Many more examples could be cited, such as Lenovo’s rapid acquisition of foreign patents to fuel entry into new areas, or Wuxi Pharma Tech (NYSE: WX) and their collaboration with Germany’s Targos Molecular Pathology to support WuXi's bioanalytical work for pharmaceutical customers.

The global IP community was surprised in 2014 to learn that a Chinese paper company had secured 8 billion RMB in funding (over US$1 billion) backed by its intellectual property. The story was reported in a Chinese paper-industry publication in March 2014, and a few days later we had the privilege of reporting this story to the Western world on the Innovation Fatigue blog, which was in turn quickly picked up by Intellectual Asset Management (IAM) magazine. IAM’s blog noted that this deal is one of the biggest IP-backed loans in history.

The company, Tralin Paper (Quanlin in Chinese, or Tranlin in recent U.S. stories), has a modest portfolio with around 100 Chinese patents, several internationally-filed patents and a few trademarks. Their technical strength is in creating paper with natural characteristics from waste paper and straw. Even if guanxi rather than IP was behind the financing, the fact that IP was used as publicized basis for the deal underscores the increasing importance of IP in China and the diverse ways in which Chinese IP can generate value. For Tralin, even if the IP were window dressing, its role even as a prop at a minimum provided PR value and strengthened Tralin’s position as thought leader in its niche. The most reasonable assumption is that IP also provided direct financial benefits, not just window dressing.

In the U.S., where Chinese innovation and IP is often deprecated, the impact of this deal is being felt strongly as Tralin/Tranlin is investing $2 billion in Virginia and creating 2,000 jobs with the technology they are bringing to U.S. shores. News stories so far have missed the connection between U.S. jobs and Tranlin’s ability to get capital based on Chinese IP, but we hope that Americans might recognize that innovation and IP from China is at least partly responsible for this welcome job growth.

Tralin/Tranlin’s story is part of a landscape in China where entrepreneurs and creative leaders are discovering the many positive uses of IP, including its ability to secure capital and build partnerships. But many Western companies wishing to build partnerships with their technology fear China and the risk of misappropriated IP. This lack of trust is being addressed gradually as China strengthens its IP laws and IP enforcement systems. Lawsuits, no matter how fair, are a last resort. Successful joint innovation requires trust directly between parties, and both sides need more successful examples for inspiration. Fortunately, a powerful role model of the technical, cultural, and political bridge-building that can occur in a healthy relationship rooted in carefully-maintained trust can be seen in a remarkable experiment in technology transfer and international cooperation: the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership.

In Jinshan, China, a heavily populated district of Shanghai, composting was previously the only option for managing dairy waste. Unfortunately, the traditional way of letting manure decompose in the sun resulted in the release of unpleasant odor, the greenhouse gas methane, and manure-tainted runoff water into rivers. The situation in Jinshan is improving with the help of advanced anaerobic digesters designed by a U.S. professor at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Utah. Using this technology, pollution and solid waste were reduced by nearly half as 10,000 gallons/day of manure-rich slurry is treated. For the Jinshan Clean Energy Project, IP from the U.S. has been successfully transferred and adapted for use in China to solve a substantial environmental problem.

This invention addresses significant problems in the biogas field. The biogas coming from animal waste is methane contaminated with corrosive hydrogen sulfide and water vapor that needs to be removed before it can be used as a fuel. Biogas conditioners on the market may cost over $500,000. However, with the system patented by BYU professors, a conditioner can clean up biogas for one-eighth of the cost. The clean gas can be compressed for use in power generators and engines or converted to liquid biodiesel. Hansen's technology was brought to China in partnership with a Utah affiliated company and UQEP.

Meanwhile in the Western Chinese province of Qinghai, UQEP’s work includes initiatives to deal with heavy metals in water, capture of CO2, soil remediation, and clean up hazardous waste sites. These projects involve collaboration between China and a growing cluster of U.S. green tech companies such as Metallosensors. Partnership models similar to the Jinshan project are applied to solve further environmental challenges in China.

Metallosensors, for example, deals with heavy metals such as mercury, with innovative cost-effective and rapid methods to detect those pollutants. Since the waterways in Qinghai Province are important sources of water for China and Asia, reducing pollution in Qinghai is vitally important for the region. Utah Science Technology and Research (USTAR) professor Ling Zang from University of Utah is behind the mercury detection technology being commercialized by Metallosensors. This technology will be used to help manage heavy metals in Qinghai and elsewhere. The joint IP project between Metallosensors and UQEP involves licensing and respecting Metallosensors’ intellectual property, while effectively dealing with Chinese policy on IP and local funding.

The soil remediation project mentioned above involves technology from the University of Utah that is removing pollutants in the soil near the city of Wuxi (population 5 million) on the shores of Lake Taihu, which suffered devastating toxic algae blooms in 2007, linked to industrial pollutants. The situation in Wuxi presented an opportunity for collaboration between the Utah clean technology industry and a UQEP affiliated local partner in Shanghai. This local partner proposed a pilot demonstration project aimed at soil remediation in Wuxi. Using “heightened ozonation treatment” or HOT, developed by a professor at the University of Utah, UQEP’s Shanghai affiliated company would engineer a small-scale plant near Taihu Lake aimed at testing the remediation process on some of the soil on a plot formerly occupied by chemical industry factories. The project would require pioneering a new model for U.S.-China joint collaboration, IP protection, technology transfer, and policy implementation. The success of the project would provide a blueprint for future U.S.-China efforts in environmental clean technology that would pave the way for UQEP.

UQEP is a non-profit organization jointly supported by the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the Chinese National Development and Reform Commission. UQEP is "dedicated to building relationships, protecting intellectual property, and developing green technologies." The EcoPartnership between the State of Utah and the province of Qinghai draws upon similarities between the two. Both are western regions in their nations with high mountains, salt lakes and diverse cultures.

Inspired by these common elements, then Governor of Qinghai Province, Luo Huining, and Utah Governor Gary Herbert, developed a partnership aimed at joint innovation for environmental sustainability.

Inspired by these common elements, then Governor of Qinghai Province, Luo Huining, and Utah Governor Gary Herbert, developed a partnership aimed at joint innovation for environmental sustainability.

Though UQEP was launched in 2011, its foundation began earlier with bonds of trust developed between Utah government leaders, businesses, and universities with partners in China. In 2009, a Chinese UQEP-affiliated company, Honde, was established as an environmental technology company in partnership with the Utah government, universities, and clean technology businesses. One of its aims was to develop Utah-China relationships to set the stage for future collaboration and innovation. Honde’s mission was envisioned by Shawn Hu, a Chinese national who for over a decade worked as the Trade Representative for the state of Utah in China. Mr. Hu envisioned a collaborative trust platform emphasizing IP protection while promoting technology transfer and joint-research. With support from Utah government, the collaborative platform evolved into UQEP and in 2011 it was inducted into the EcoPartnership program.

UQEP is one of thirty-two EcoPartnerships and is the only state-province level EcoPartnership. It reaches far deeper than the state-province relationship with additional partnerships including cities, districts, universities, and local businesses. Generally, EcoPartnerships promote clean air, water, or transportation; clean, electricity; conservation of forests and wetlands. In July 2014 during the 6th round of the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue in Beijing, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry described the role of the EcoPartnership program as one of ”harnessing the ingenuity and the innovation of the private sector, universities, civil society, in order to promote economic growth, energy security, and environmental sustainability.” Qinghai province has already invested several million RMB in UQEP projects, and other government bodies in China are also active supporters. UQEP also collaborates with Purdue University scientists, thanks to the Purdue-led Eco-Partnership for Environmental Sustainability. One example of the benefits from joint efforts with Purdue is a project begun in 2014 aimed at improving water quality in Qinghai using advanced versions of a "slow sand filtration" system developed by Purdue's Chad Jahvert, professor of environmental engineering. The purification system is based on readily available resources and natural aerobic processes to break down pollutants in water. This technology transfer effort has already resulted in improved water quality for several families in Qinghai’s Dongshan township, where drinking water had largely come from untreated, turbid rainwater collected in cellars.

While the EcoPartnership brings obvious benefits to China as it gains access to technology and expertise to solve environmental problems, the benefits for the U.S. partners are also noteworthy. For Utah, the EcoPartnership:

- • Opens new markets for green technologies;

- • Provides large-scale cost effective testing of R&D concepts;

- • Increases cultural understanding by creating international fellowship opportunities for U.S. students and professionals;

- • Provides Utah businesses with a leadership edge in environmental technology through collaborating with China;

- • Gives U.S. partners early access to relevant research results from Chinese teams;

A lesson from the UQEP projects has been the importance of trust as a foundation for collaboration. This involves far more than lawyers and contracts.

Many Westerners have heard of guanxi. What is often missed is that guanxi is more than merely knowing others. Most importantly, it refers to relationships of trust that can take years to cultivate and involve effort to maintain. Trust is tied to reputation, and above all, UQEP's success came from a carefully earned reputation, especially that of Honde and the leaders behind UQEP. It took years of reputation building to reach the point where political barriers could be gently but vigorously moved aside to achieve mutual good in an experiment that is actively advancing China's environmental situation, Utah's commercialization of technology, and U.S.-China relations.

UQEP's experience also shows that trust is best established through face-to-face exchanges and incremental agreements leading to action.

Another important lesson taught by Honde's founder, Shawn Hu, is that doing business in China requires extreme patience followed by quick and efficient action. Building trust and gaining support for complex and sensitive projects with local and national governments can take years of navigating complex systems, but when the window of opportunity comes, rapid progress with demonstrated success is required. Thus, Honde carefully chose both the timing and the location of its projects to achieve success. This route creates momentum for future projects.

UQEP's story also points to the importance placed on IP respect. Many U.S. entities fear bringing their IP to China. One interesting approach to overcoming these fears was taken by Honde for the Wuxi project, wherein Honde licensed HOT technology, signing confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements, and requiring the same of local partners in Wuxi. Honde closely monitors the design, manufacture, and operation of HOT equipment and holds IP training sessions to establish a culture of IP respect. This culture has also been shared and emphasized during exchanges with local Chinese government leaders who have acknowledged the importance of protecting IP in order to continue doing business with U.S. companies.

As one of many indications of the significant government support UQEP is enjoying, a document signed by the governor of Qinghai Province makes the following declaration:

“…In order to assist the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership in successfully achieving their goals, all functioning departments and major cities are required to proactively support the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership by enhancing organization and coordination, creating a better atmosphere for cooperation and development, further encouraging cooperation in additional areas, and by specifically including the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership in individual action plans…”

Building the foundation of trust has taken years of patience and education. Chinese and American partners have both had substantial misapprehensions to overcome. UQEP's leaders and supporters have learned, though, that barriers can be circumnavigated with a combination of patience and swift action when the time is right.

There are also differences in perspectives regarding time and timing. The Chinese often feel that there is no permanency and thus questionable reliability on the U.S. side, for they see leadership changing all the time, with policies and funding rapidly shifting vacillating. Further, there is inherent distrust of outsiders on both sides. To deal with such challenges, UQEP relies on a platform that starts with academia and then brings in business and government as they look for a suitable joint project to build trust. When the timing is right, an opportunity may be pursued swiftly even if the project is not a perfect match.

UQEP has learned that fostering trust involves many meetings. Shawn Hu participated in over 60 meetings with various Chinese leaders to coordinate the Jinshan biogas project. Foreigners may not be used to this level of background work, but this is an important part of the local process in developing trust. The Chinese way is that if they like the project and the people, they will take risks to move ahead in spite of uncertainty. In this way, projects can swiftly cut through normal slow routes. This is part of an increasingly fast-paced culture in China that is often challenging for foreigners to understand or follow. When the timing is right and the foundations in place, the pace of innovation in China can surprise Western partners.

The power of open innovation is best tapped when there is a foundation of trust between partners, coupled with IP that can be used to meet compelling needs. The Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership is an excellent example of international open innovation that overcomes cultural and political boundaries, brings significant mutual benefit, and solves environmental problems. It also defies old stereotypes and demonstrates China’s coming of age in terms of IP respect. The foundation laid by UQEP can be expected to influence many future collaborative efforts in other areas.

Jeffrey D. Lindsay is Head of Intellectual Property at Asia Pulp & Paper in Shanghai. Edgar Gomez is a business consultant, researcher, and photographer. Alan Taylor Smurthwaite currently serves as the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership Intellectual Property and Innovation Coordinator managing environmental sustainability initiatives in Qinghai Province.

Second photo: Clean energy biogas facility in the Jinshan district of Shanghai, China. Courtesy of UQEP.

Third photo: Utah Governor Gary Herbert and the then Governor of Qinghhai province Luo Huining at the launching ceremony in Salt Lake City of the Utah-Qinghai EcoPartnership. Photo by David Monson.

This article was originally published in the Diplomatic Courier's November/December 2014 print edition.