.

Since at least the late nineteenth century, the forces of globalization and naval power have been closely intertwined. Prior to the First World War, British naval strength underwrote the international gold based economy, while today the dominance of the U.S. Navy facilitates free access to the maritime commons that are the lifeblood of the current international system. However, as much as naval power has preserved global order, it has proved to be an equally disruptive force, a phenomenon dating back to Ancient Greece.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, rising powers such as Imperial Japan and the United States invested heavily in maritime power and handily won wars against old guard empires, achieving decisive victories against the navies of Russia and Spain, respectively. The historical examples of Japan and the United States are particularly relevant today, as tensions in Asia’s contested waters have prompted fears that a ‘short, sharp’ war in the disputed South China Sea between Chinese and U.S. naval forces may lead to a U.S. defeat - an American Tsushima, so to speak. While the current superiority gap between the U.S. Navy and its Chinese counterpart means that such a scenario is unlikely in the near future, the lessons of previous naval conflicts can and must inform America’s long-term strategy regarding the region.

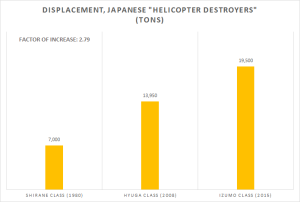

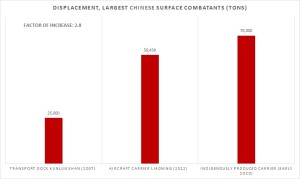

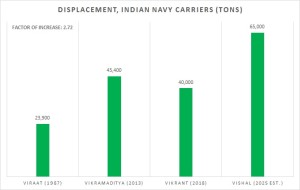

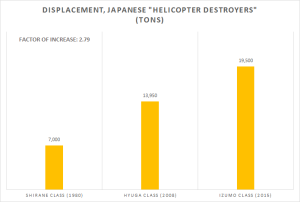

Today, regional powers such as India, China, and Japan are engaging in the unprecedented development of capital ships, which will greatly increase the ability of these countries to exert their influence in the neighborhood. While these vessels do not directly threaten U.S. interests by themselves, they represent a notable shift in Asian naval policy and indicate the beginnings of a dangerous naval escalation. Imperial Japan and the United States started their rise to maritime dominance with the acquisition of only a few capital ships, but the very decision to acquire such powerful military hardware in the first place represented the beginnings of a more assertive and aggressive foreign policy. Within the space of a few decades, both of these nations had turned their unimpressive navies into world-class forces with equally grand ambitions.

Today, regional powers such as India, China, and Japan are engaging in the unprecedented development of capital ships, which will greatly increase the ability of these countries to exert their influence in the neighborhood. While these vessels do not directly threaten U.S. interests by themselves, they represent a notable shift in Asian naval policy and indicate the beginnings of a dangerous naval escalation. Imperial Japan and the United States started their rise to maritime dominance with the acquisition of only a few capital ships, but the very decision to acquire such powerful military hardware in the first place represented the beginnings of a more assertive and aggressive foreign policy. Within the space of a few decades, both of these nations had turned their unimpressive navies into world-class forces with equally grand ambitions.

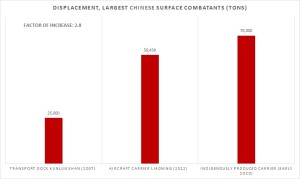

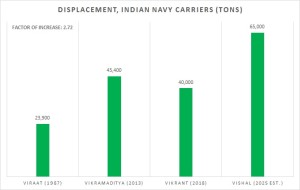

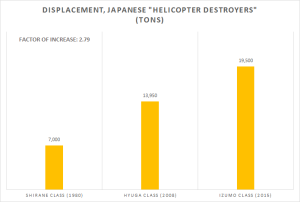

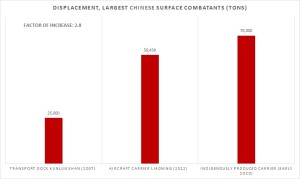

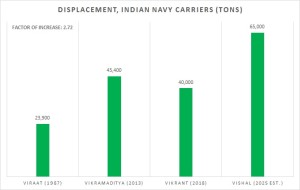

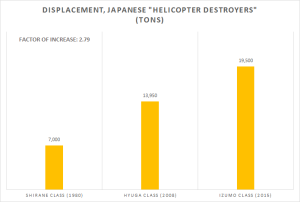

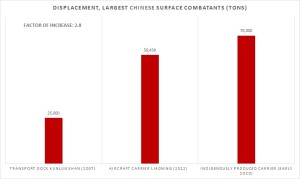

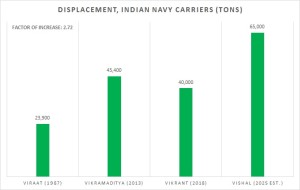

In the present day, new Asian carriers the likes of China’s Liaoning, Japan’s Izumo, and India’s Vikrant dwarf the size of any previous ship in their respective navies. In the case of China and India, indigenous carrier projects are slated to deliver even larger vessels by the beginning of the next decade. If these dramatic surges in naval power accompany commensurate increases in regional ambition, the vast Indian Ocean and Pacific regions may quickly become too small to accommodate the jostling of Asian naval powers spurred on by fearful or nationalistic publics. Considering the numerous defense commitments and economic interests the U.S. maintains in the region, any resultant naval clash would swiftly entangle the United States.

In the present day, new Asian carriers the likes of China’s Liaoning, Japan’s Izumo, and India’s Vikrant dwarf the size of any previous ship in their respective navies. In the case of China and India, indigenous carrier projects are slated to deliver even larger vessels by the beginning of the next decade. If these dramatic surges in naval power accompany commensurate increases in regional ambition, the vast Indian Ocean and Pacific regions may quickly become too small to accommodate the jostling of Asian naval powers spurred on by fearful or nationalistic publics. Considering the numerous defense commitments and economic interests the U.S. maintains in the region, any resultant naval clash would swiftly entangle the United States.

Therefore, American policy needs to focus on the long-term possibility that increasingly powerful Asian naval forces will both amplify regional tensions and make it more difficult for the U.S. to exercise influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the American navy might reign supreme for now, disruptive technologies and the underestimation of rivals have often caused the collapse of many great powers.

While the U.S. may not be able to prevent an Asian naval buildup, it can at least ensure that the rise of Asian regional powers remains a peaceful and equitable process. Therefore, the United States can best promote regional stability in the coming decades by leveraging its diplomatic influence and technological prowess to ensure that no regional navy is capable of dominating its neighbors. A joint collaboration with India to develop an indigenously produced carrier is an important first step in this direction that will both enhance diplomatic ties and bolster friendly naval capacity. On the rhetorical side, the United States must firmly assert that it is totally committed to protecting the security and territorial integrity of its regional partners. Any statements to the contrary will wholly undermine any efforts to reduce tensions. As seen by the case of the Persian Gulf states, talk of ‘pivots’ and rhetorical wavering over red lines can and will prompt American allies to take matters into their own hands, leading to greater escalation and diminished U.S. influence.

It is long term strategies such as these that should serve as the linchpins of America’s Asia policy going forward – comprehensive plans that address objectives ten and twenty years out, rather than only focusing on the challenges of next year. While the United States cannot totally predict what India, China, and Japan’s navies will look like in the coming decades, the lessons of history show that the naval gains of up-and-coming nations often come as unpleasant surprises to incumbent powers. While America’s navy may presently outclass its Asian counterparts, current superiority is no excuse for smug complacency.

Therefore, American policy needs to focus on the long-term possibility that increasingly powerful Asian naval forces will both amplify regional tensions and make it more difficult for the U.S. to exercise influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the American navy might reign supreme for now, disruptive technologies and the underestimation of rivals have often caused the collapse of many great powers.

While the U.S. may not be able to prevent an Asian naval buildup, it can at least ensure that the rise of Asian regional powers remains a peaceful and equitable process. Therefore, the United States can best promote regional stability in the coming decades by leveraging its diplomatic influence and technological prowess to ensure that no regional navy is capable of dominating its neighbors. A joint collaboration with India to develop an indigenously produced carrier is an important first step in this direction that will both enhance diplomatic ties and bolster friendly naval capacity. On the rhetorical side, the United States must firmly assert that it is totally committed to protecting the security and territorial integrity of its regional partners. Any statements to the contrary will wholly undermine any efforts to reduce tensions. As seen by the case of the Persian Gulf states, talk of ‘pivots’ and rhetorical wavering over red lines can and will prompt American allies to take matters into their own hands, leading to greater escalation and diminished U.S. influence.

It is long term strategies such as these that should serve as the linchpins of America’s Asia policy going forward – comprehensive plans that address objectives ten and twenty years out, rather than only focusing on the challenges of next year. While the United States cannot totally predict what India, China, and Japan’s navies will look like in the coming decades, the lessons of history show that the naval gains of up-and-coming nations often come as unpleasant surprises to incumbent powers. While America’s navy may presently outclass its Asian counterparts, current superiority is no excuse for smug complacency.

Today, regional powers such as India, China, and Japan are engaging in the unprecedented development of capital ships, which will greatly increase the ability of these countries to exert their influence in the neighborhood. While these vessels do not directly threaten U.S. interests by themselves, they represent a notable shift in Asian naval policy and indicate the beginnings of a dangerous naval escalation. Imperial Japan and the United States started their rise to maritime dominance with the acquisition of only a few capital ships, but the very decision to acquire such powerful military hardware in the first place represented the beginnings of a more assertive and aggressive foreign policy. Within the space of a few decades, both of these nations had turned their unimpressive navies into world-class forces with equally grand ambitions.

Today, regional powers such as India, China, and Japan are engaging in the unprecedented development of capital ships, which will greatly increase the ability of these countries to exert their influence in the neighborhood. While these vessels do not directly threaten U.S. interests by themselves, they represent a notable shift in Asian naval policy and indicate the beginnings of a dangerous naval escalation. Imperial Japan and the United States started their rise to maritime dominance with the acquisition of only a few capital ships, but the very decision to acquire such powerful military hardware in the first place represented the beginnings of a more assertive and aggressive foreign policy. Within the space of a few decades, both of these nations had turned their unimpressive navies into world-class forces with equally grand ambitions.

In the present day, new Asian carriers the likes of China’s Liaoning, Japan’s Izumo, and India’s Vikrant dwarf the size of any previous ship in their respective navies. In the case of China and India, indigenous carrier projects are slated to deliver even larger vessels by the beginning of the next decade. If these dramatic surges in naval power accompany commensurate increases in regional ambition, the vast Indian Ocean and Pacific regions may quickly become too small to accommodate the jostling of Asian naval powers spurred on by fearful or nationalistic publics. Considering the numerous defense commitments and economic interests the U.S. maintains in the region, any resultant naval clash would swiftly entangle the United States.

In the present day, new Asian carriers the likes of China’s Liaoning, Japan’s Izumo, and India’s Vikrant dwarf the size of any previous ship in their respective navies. In the case of China and India, indigenous carrier projects are slated to deliver even larger vessels by the beginning of the next decade. If these dramatic surges in naval power accompany commensurate increases in regional ambition, the vast Indian Ocean and Pacific regions may quickly become too small to accommodate the jostling of Asian naval powers spurred on by fearful or nationalistic publics. Considering the numerous defense commitments and economic interests the U.S. maintains in the region, any resultant naval clash would swiftly entangle the United States.

Therefore, American policy needs to focus on the long-term possibility that increasingly powerful Asian naval forces will both amplify regional tensions and make it more difficult for the U.S. to exercise influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the American navy might reign supreme for now, disruptive technologies and the underestimation of rivals have often caused the collapse of many great powers.

While the U.S. may not be able to prevent an Asian naval buildup, it can at least ensure that the rise of Asian regional powers remains a peaceful and equitable process. Therefore, the United States can best promote regional stability in the coming decades by leveraging its diplomatic influence and technological prowess to ensure that no regional navy is capable of dominating its neighbors. A joint collaboration with India to develop an indigenously produced carrier is an important first step in this direction that will both enhance diplomatic ties and bolster friendly naval capacity. On the rhetorical side, the United States must firmly assert that it is totally committed to protecting the security and territorial integrity of its regional partners. Any statements to the contrary will wholly undermine any efforts to reduce tensions. As seen by the case of the Persian Gulf states, talk of ‘pivots’ and rhetorical wavering over red lines can and will prompt American allies to take matters into their own hands, leading to greater escalation and diminished U.S. influence.

It is long term strategies such as these that should serve as the linchpins of America’s Asia policy going forward – comprehensive plans that address objectives ten and twenty years out, rather than only focusing on the challenges of next year. While the United States cannot totally predict what India, China, and Japan’s navies will look like in the coming decades, the lessons of history show that the naval gains of up-and-coming nations often come as unpleasant surprises to incumbent powers. While America’s navy may presently outclass its Asian counterparts, current superiority is no excuse for smug complacency.

Therefore, American policy needs to focus on the long-term possibility that increasingly powerful Asian naval forces will both amplify regional tensions and make it more difficult for the U.S. to exercise influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the American navy might reign supreme for now, disruptive technologies and the underestimation of rivals have often caused the collapse of many great powers.

While the U.S. may not be able to prevent an Asian naval buildup, it can at least ensure that the rise of Asian regional powers remains a peaceful and equitable process. Therefore, the United States can best promote regional stability in the coming decades by leveraging its diplomatic influence and technological prowess to ensure that no regional navy is capable of dominating its neighbors. A joint collaboration with India to develop an indigenously produced carrier is an important first step in this direction that will both enhance diplomatic ties and bolster friendly naval capacity. On the rhetorical side, the United States must firmly assert that it is totally committed to protecting the security and territorial integrity of its regional partners. Any statements to the contrary will wholly undermine any efforts to reduce tensions. As seen by the case of the Persian Gulf states, talk of ‘pivots’ and rhetorical wavering over red lines can and will prompt American allies to take matters into their own hands, leading to greater escalation and diminished U.S. influence.

It is long term strategies such as these that should serve as the linchpins of America’s Asia policy going forward – comprehensive plans that address objectives ten and twenty years out, rather than only focusing on the challenges of next year. While the United States cannot totally predict what India, China, and Japan’s navies will look like in the coming decades, the lessons of history show that the naval gains of up-and-coming nations often come as unpleasant surprises to incumbent powers. While America’s navy may presently outclass its Asian counterparts, current superiority is no excuse for smug complacency.The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.

a global affairs media network

How the U.S. Can Address the Implications of Growing Asian Naval Power

Bow of a pink and grey cargo ship.|||

November 24, 2015

Since at least the late nineteenth century, the forces of globalization and naval power have been closely intertwined. Prior to the First World War, British naval strength underwrote the international gold based economy, while today the dominance of the U.S. Navy facilitates free access to the maritime commons that are the lifeblood of the current international system. However, as much as naval power has preserved global order, it has proved to be an equally disruptive force, a phenomenon dating back to Ancient Greece.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, rising powers such as Imperial Japan and the United States invested heavily in maritime power and handily won wars against old guard empires, achieving decisive victories against the navies of Russia and Spain, respectively. The historical examples of Japan and the United States are particularly relevant today, as tensions in Asia’s contested waters have prompted fears that a ‘short, sharp’ war in the disputed South China Sea between Chinese and U.S. naval forces may lead to a U.S. defeat - an American Tsushima, so to speak. While the current superiority gap between the U.S. Navy and its Chinese counterpart means that such a scenario is unlikely in the near future, the lessons of previous naval conflicts can and must inform America’s long-term strategy regarding the region.

Today, regional powers such as India, China, and Japan are engaging in the unprecedented development of capital ships, which will greatly increase the ability of these countries to exert their influence in the neighborhood. While these vessels do not directly threaten U.S. interests by themselves, they represent a notable shift in Asian naval policy and indicate the beginnings of a dangerous naval escalation. Imperial Japan and the United States started their rise to maritime dominance with the acquisition of only a few capital ships, but the very decision to acquire such powerful military hardware in the first place represented the beginnings of a more assertive and aggressive foreign policy. Within the space of a few decades, both of these nations had turned their unimpressive navies into world-class forces with equally grand ambitions.

Today, regional powers such as India, China, and Japan are engaging in the unprecedented development of capital ships, which will greatly increase the ability of these countries to exert their influence in the neighborhood. While these vessels do not directly threaten U.S. interests by themselves, they represent a notable shift in Asian naval policy and indicate the beginnings of a dangerous naval escalation. Imperial Japan and the United States started their rise to maritime dominance with the acquisition of only a few capital ships, but the very decision to acquire such powerful military hardware in the first place represented the beginnings of a more assertive and aggressive foreign policy. Within the space of a few decades, both of these nations had turned their unimpressive navies into world-class forces with equally grand ambitions.

In the present day, new Asian carriers the likes of China’s Liaoning, Japan’s Izumo, and India’s Vikrant dwarf the size of any previous ship in their respective navies. In the case of China and India, indigenous carrier projects are slated to deliver even larger vessels by the beginning of the next decade. If these dramatic surges in naval power accompany commensurate increases in regional ambition, the vast Indian Ocean and Pacific regions may quickly become too small to accommodate the jostling of Asian naval powers spurred on by fearful or nationalistic publics. Considering the numerous defense commitments and economic interests the U.S. maintains in the region, any resultant naval clash would swiftly entangle the United States.

In the present day, new Asian carriers the likes of China’s Liaoning, Japan’s Izumo, and India’s Vikrant dwarf the size of any previous ship in their respective navies. In the case of China and India, indigenous carrier projects are slated to deliver even larger vessels by the beginning of the next decade. If these dramatic surges in naval power accompany commensurate increases in regional ambition, the vast Indian Ocean and Pacific regions may quickly become too small to accommodate the jostling of Asian naval powers spurred on by fearful or nationalistic publics. Considering the numerous defense commitments and economic interests the U.S. maintains in the region, any resultant naval clash would swiftly entangle the United States.

Therefore, American policy needs to focus on the long-term possibility that increasingly powerful Asian naval forces will both amplify regional tensions and make it more difficult for the U.S. to exercise influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the American navy might reign supreme for now, disruptive technologies and the underestimation of rivals have often caused the collapse of many great powers.

While the U.S. may not be able to prevent an Asian naval buildup, it can at least ensure that the rise of Asian regional powers remains a peaceful and equitable process. Therefore, the United States can best promote regional stability in the coming decades by leveraging its diplomatic influence and technological prowess to ensure that no regional navy is capable of dominating its neighbors. A joint collaboration with India to develop an indigenously produced carrier is an important first step in this direction that will both enhance diplomatic ties and bolster friendly naval capacity. On the rhetorical side, the United States must firmly assert that it is totally committed to protecting the security and territorial integrity of its regional partners. Any statements to the contrary will wholly undermine any efforts to reduce tensions. As seen by the case of the Persian Gulf states, talk of ‘pivots’ and rhetorical wavering over red lines can and will prompt American allies to take matters into their own hands, leading to greater escalation and diminished U.S. influence.

It is long term strategies such as these that should serve as the linchpins of America’s Asia policy going forward – comprehensive plans that address objectives ten and twenty years out, rather than only focusing on the challenges of next year. While the United States cannot totally predict what India, China, and Japan’s navies will look like in the coming decades, the lessons of history show that the naval gains of up-and-coming nations often come as unpleasant surprises to incumbent powers. While America’s navy may presently outclass its Asian counterparts, current superiority is no excuse for smug complacency.

Therefore, American policy needs to focus on the long-term possibility that increasingly powerful Asian naval forces will both amplify regional tensions and make it more difficult for the U.S. to exercise influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the American navy might reign supreme for now, disruptive technologies and the underestimation of rivals have often caused the collapse of many great powers.

While the U.S. may not be able to prevent an Asian naval buildup, it can at least ensure that the rise of Asian regional powers remains a peaceful and equitable process. Therefore, the United States can best promote regional stability in the coming decades by leveraging its diplomatic influence and technological prowess to ensure that no regional navy is capable of dominating its neighbors. A joint collaboration with India to develop an indigenously produced carrier is an important first step in this direction that will both enhance diplomatic ties and bolster friendly naval capacity. On the rhetorical side, the United States must firmly assert that it is totally committed to protecting the security and territorial integrity of its regional partners. Any statements to the contrary will wholly undermine any efforts to reduce tensions. As seen by the case of the Persian Gulf states, talk of ‘pivots’ and rhetorical wavering over red lines can and will prompt American allies to take matters into their own hands, leading to greater escalation and diminished U.S. influence.

It is long term strategies such as these that should serve as the linchpins of America’s Asia policy going forward – comprehensive plans that address objectives ten and twenty years out, rather than only focusing on the challenges of next year. While the United States cannot totally predict what India, China, and Japan’s navies will look like in the coming decades, the lessons of history show that the naval gains of up-and-coming nations often come as unpleasant surprises to incumbent powers. While America’s navy may presently outclass its Asian counterparts, current superiority is no excuse for smug complacency.

Today, regional powers such as India, China, and Japan are engaging in the unprecedented development of capital ships, which will greatly increase the ability of these countries to exert their influence in the neighborhood. While these vessels do not directly threaten U.S. interests by themselves, they represent a notable shift in Asian naval policy and indicate the beginnings of a dangerous naval escalation. Imperial Japan and the United States started their rise to maritime dominance with the acquisition of only a few capital ships, but the very decision to acquire such powerful military hardware in the first place represented the beginnings of a more assertive and aggressive foreign policy. Within the space of a few decades, both of these nations had turned their unimpressive navies into world-class forces with equally grand ambitions.

Today, regional powers such as India, China, and Japan are engaging in the unprecedented development of capital ships, which will greatly increase the ability of these countries to exert their influence in the neighborhood. While these vessels do not directly threaten U.S. interests by themselves, they represent a notable shift in Asian naval policy and indicate the beginnings of a dangerous naval escalation. Imperial Japan and the United States started their rise to maritime dominance with the acquisition of only a few capital ships, but the very decision to acquire such powerful military hardware in the first place represented the beginnings of a more assertive and aggressive foreign policy. Within the space of a few decades, both of these nations had turned their unimpressive navies into world-class forces with equally grand ambitions.

In the present day, new Asian carriers the likes of China’s Liaoning, Japan’s Izumo, and India’s Vikrant dwarf the size of any previous ship in their respective navies. In the case of China and India, indigenous carrier projects are slated to deliver even larger vessels by the beginning of the next decade. If these dramatic surges in naval power accompany commensurate increases in regional ambition, the vast Indian Ocean and Pacific regions may quickly become too small to accommodate the jostling of Asian naval powers spurred on by fearful or nationalistic publics. Considering the numerous defense commitments and economic interests the U.S. maintains in the region, any resultant naval clash would swiftly entangle the United States.

In the present day, new Asian carriers the likes of China’s Liaoning, Japan’s Izumo, and India’s Vikrant dwarf the size of any previous ship in their respective navies. In the case of China and India, indigenous carrier projects are slated to deliver even larger vessels by the beginning of the next decade. If these dramatic surges in naval power accompany commensurate increases in regional ambition, the vast Indian Ocean and Pacific regions may quickly become too small to accommodate the jostling of Asian naval powers spurred on by fearful or nationalistic publics. Considering the numerous defense commitments and economic interests the U.S. maintains in the region, any resultant naval clash would swiftly entangle the United States.

Therefore, American policy needs to focus on the long-term possibility that increasingly powerful Asian naval forces will both amplify regional tensions and make it more difficult for the U.S. to exercise influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the American navy might reign supreme for now, disruptive technologies and the underestimation of rivals have often caused the collapse of many great powers.

While the U.S. may not be able to prevent an Asian naval buildup, it can at least ensure that the rise of Asian regional powers remains a peaceful and equitable process. Therefore, the United States can best promote regional stability in the coming decades by leveraging its diplomatic influence and technological prowess to ensure that no regional navy is capable of dominating its neighbors. A joint collaboration with India to develop an indigenously produced carrier is an important first step in this direction that will both enhance diplomatic ties and bolster friendly naval capacity. On the rhetorical side, the United States must firmly assert that it is totally committed to protecting the security and territorial integrity of its regional partners. Any statements to the contrary will wholly undermine any efforts to reduce tensions. As seen by the case of the Persian Gulf states, talk of ‘pivots’ and rhetorical wavering over red lines can and will prompt American allies to take matters into their own hands, leading to greater escalation and diminished U.S. influence.

It is long term strategies such as these that should serve as the linchpins of America’s Asia policy going forward – comprehensive plans that address objectives ten and twenty years out, rather than only focusing on the challenges of next year. While the United States cannot totally predict what India, China, and Japan’s navies will look like in the coming decades, the lessons of history show that the naval gains of up-and-coming nations often come as unpleasant surprises to incumbent powers. While America’s navy may presently outclass its Asian counterparts, current superiority is no excuse for smug complacency.

Therefore, American policy needs to focus on the long-term possibility that increasingly powerful Asian naval forces will both amplify regional tensions and make it more difficult for the U.S. to exercise influence in the Asia-Pacific region. Although the American navy might reign supreme for now, disruptive technologies and the underestimation of rivals have often caused the collapse of many great powers.

While the U.S. may not be able to prevent an Asian naval buildup, it can at least ensure that the rise of Asian regional powers remains a peaceful and equitable process. Therefore, the United States can best promote regional stability in the coming decades by leveraging its diplomatic influence and technological prowess to ensure that no regional navy is capable of dominating its neighbors. A joint collaboration with India to develop an indigenously produced carrier is an important first step in this direction that will both enhance diplomatic ties and bolster friendly naval capacity. On the rhetorical side, the United States must firmly assert that it is totally committed to protecting the security and territorial integrity of its regional partners. Any statements to the contrary will wholly undermine any efforts to reduce tensions. As seen by the case of the Persian Gulf states, talk of ‘pivots’ and rhetorical wavering over red lines can and will prompt American allies to take matters into their own hands, leading to greater escalation and diminished U.S. influence.

It is long term strategies such as these that should serve as the linchpins of America’s Asia policy going forward – comprehensive plans that address objectives ten and twenty years out, rather than only focusing on the challenges of next year. While the United States cannot totally predict what India, China, and Japan’s navies will look like in the coming decades, the lessons of history show that the naval gains of up-and-coming nations often come as unpleasant surprises to incumbent powers. While America’s navy may presently outclass its Asian counterparts, current superiority is no excuse for smug complacency.The views presented in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of any other organization.