hough the novel coronavirus has infected communities in every corner of the world, the disease hasn’t infected every country equally. In Europe, the disease has hit Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom particularly hard. Germany, on the other hand, has been more successful in containing the disease. In Asia, Taiwan saw its first coronavirus case within ten days of Italy’s. By mid-March, Taiwan had recorded just two deaths among 153 cases. During the same time, in sharp contrast, Italy recorded over 47,000 cases with over 4,000 deaths.

A multitude of factors have accounted for countries’ varied experiences with the novel coronavirus. Italy, for example, was said to be hit particularly hard in part because the country hosts the world’s second-oldest population. Germany’s Minister of Health attributed his country’s coronavirus success to a strong national healthcare system, adequate pandemic preparation, and robust virus testing. And in Taiwan, early government response paved the way to a contained coronavirus case load.

Experts tried to use information from some of the first countries hit by coronavirus to predict who might be hardest hit by the disease in the future. In March, one American demographer commenting on the Italian experience with coronavirus speculated that Florida was like an “uber-Italy” with its large population of retirees, and thus likely to be susceptible to a “tough situation” as coronavirus spread across the United States. However, despite dire predictions, currently eight other states beat Florida in case counts, even though many feared the southern state would become the next New York.

Experts have additionally touted the benefits of national lockdowns in containing the spread in coronavirus. Indeed, in China, Germany, and Spain, lockdown policies prompted the daily infection rate to drop. However, similar lockdown policies have accompanied differing city caseloads. In the United States, for example, California and New York, two states hosting the country’s largest cities, have experienced drastically different outcomes from similarly strict lockdown policies. Though New York’s population is just half that of California, New York has had over 350,000 cases and over 27,000 deaths, while California has seen a little over 73,000 cases and almost 3,000 deaths. The fact that similar policies have produced drastically different outcomes hints at a need for stronger data analysis as countries work to manage the global coronavirus crisis.

Emsi, an American labor market analytics firm, is one company tackling the massive data analysis challenge posed by the novel coronavirus. Researchers at Emsi evaluated data from a multitude of sources to develop a Health Risk Index that can assist policymakers as they respond to the coronavirus pandemic. The Health Risk Index considers four risk factors: population preconditions, population density, workplace interaction, and population health. The risk level for each factor in the Health Risk indicator is measured on a scale of zero to one. A workplace interaction of .8, for example, indicates that a city’s workplace density is very high. The risk level of each of the four factors contributing to the Health Risk Index is then added up and divided by four. An overall risk indicator of .9 indicates a city that is very susceptible to the virus, while a risk indicator of .2 indicates a city that would likely be successful in halting viral spread.

The Health Risk Index accurately predicts COVID-19 fatalities for major U.S. cities. When researchers at Emsi graphed the Health Risk Index’s predictions against actual fatality data, the prediction line was tightly correlated to the rates of actual fatalities. This indicates that the Health Risk Index can provide insight as to why certain U.S. cities have been devastated by the coronavirus, while others have been able to halt the spread of the disease. In New York City, for example, high population density and high workplace density both contributed to the spread of the virus. Additionally, New York’s population preconditions (high incidence rates of heart disease, cancer, and chronic respiratory disease) in addition to its high population health risk (based on age, education level, and income) make America’s biggest city a hotbed for pandemic illness. The index can even help explain why Florida didn’t become “the next New York.” A healthier and less dense population, in addition to a lower rate of workplace interactions, can help explain why the sunshine state was largely spared from the scourge.

The insights of Emsi’s Health Risk Index can help any city analyze its coronavirus risk and prepare an appropriate response. For example, Emsi researchers recommend that cities with high population density “focus on protecting dense, high-traffic areas.” This can include reducing the number of riders on public transportation and regularly sanitizing high-traffic areas. Similarly, cities with a high level of workplace interaction can divide shared workspaces to limit interaction or require employees to work remotely.

Coronavirus has brought in its wake unique challenges as countries struggle to keep their populations safe. Better data analysis can help countries enact better virus-prevention and virus-containment policies. As states grapple with the possibility of a second wave of coronavirus cases, metrics like Emsi’s Health Risk Index can help all states prepare a strong government response that can be vital to saving lives.

a global affairs media network

How Data Can Help States Crush Coronavirus Caseloads

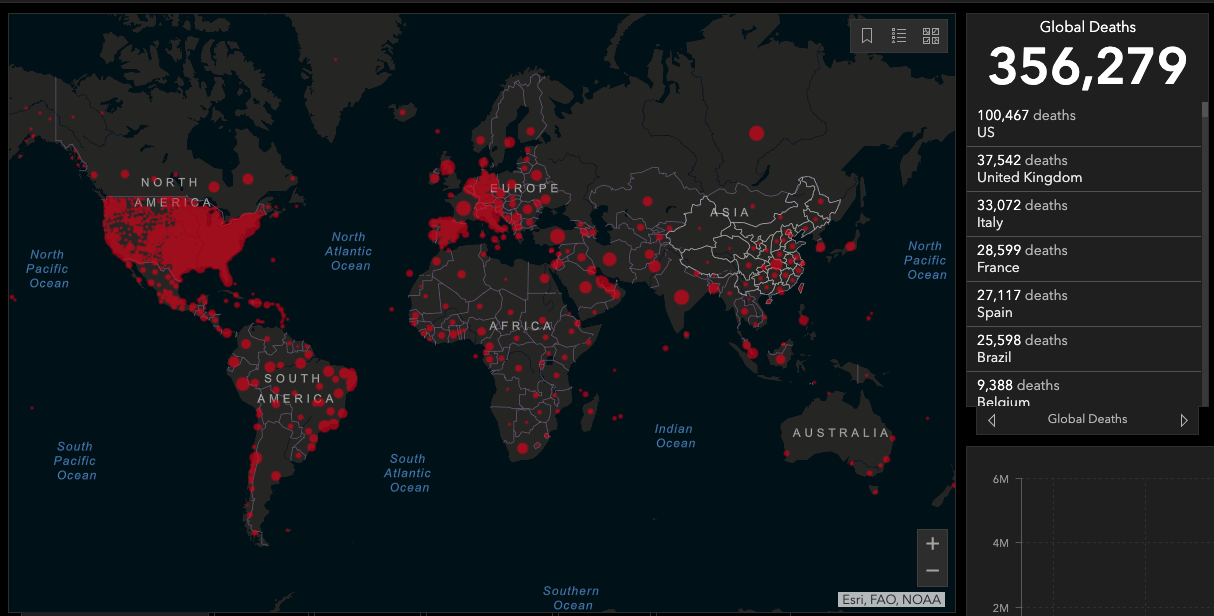

Dashboard of confirmed COVID-19 cases worldwide. Image by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at John Hopkins University.

May 30, 2020

T

hough the novel coronavirus has infected communities in every corner of the world, the disease hasn’t infected every country equally. In Europe, the disease has hit Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom particularly hard. Germany, on the other hand, has been more successful in containing the disease. In Asia, Taiwan saw its first coronavirus case within ten days of Italy’s. By mid-March, Taiwan had recorded just two deaths among 153 cases. During the same time, in sharp contrast, Italy recorded over 47,000 cases with over 4,000 deaths.

A multitude of factors have accounted for countries’ varied experiences with the novel coronavirus. Italy, for example, was said to be hit particularly hard in part because the country hosts the world’s second-oldest population. Germany’s Minister of Health attributed his country’s coronavirus success to a strong national healthcare system, adequate pandemic preparation, and robust virus testing. And in Taiwan, early government response paved the way to a contained coronavirus case load.

Experts tried to use information from some of the first countries hit by coronavirus to predict who might be hardest hit by the disease in the future. In March, one American demographer commenting on the Italian experience with coronavirus speculated that Florida was like an “uber-Italy” with its large population of retirees, and thus likely to be susceptible to a “tough situation” as coronavirus spread across the United States. However, despite dire predictions, currently eight other states beat Florida in case counts, even though many feared the southern state would become the next New York.

Experts have additionally touted the benefits of national lockdowns in containing the spread in coronavirus. Indeed, in China, Germany, and Spain, lockdown policies prompted the daily infection rate to drop. However, similar lockdown policies have accompanied differing city caseloads. In the United States, for example, California and New York, two states hosting the country’s largest cities, have experienced drastically different outcomes from similarly strict lockdown policies. Though New York’s population is just half that of California, New York has had over 350,000 cases and over 27,000 deaths, while California has seen a little over 73,000 cases and almost 3,000 deaths. The fact that similar policies have produced drastically different outcomes hints at a need for stronger data analysis as countries work to manage the global coronavirus crisis.

Emsi, an American labor market analytics firm, is one company tackling the massive data analysis challenge posed by the novel coronavirus. Researchers at Emsi evaluated data from a multitude of sources to develop a Health Risk Index that can assist policymakers as they respond to the coronavirus pandemic. The Health Risk Index considers four risk factors: population preconditions, population density, workplace interaction, and population health. The risk level for each factor in the Health Risk indicator is measured on a scale of zero to one. A workplace interaction of .8, for example, indicates that a city’s workplace density is very high. The risk level of each of the four factors contributing to the Health Risk Index is then added up and divided by four. An overall risk indicator of .9 indicates a city that is very susceptible to the virus, while a risk indicator of .2 indicates a city that would likely be successful in halting viral spread.

The Health Risk Index accurately predicts COVID-19 fatalities for major U.S. cities. When researchers at Emsi graphed the Health Risk Index’s predictions against actual fatality data, the prediction line was tightly correlated to the rates of actual fatalities. This indicates that the Health Risk Index can provide insight as to why certain U.S. cities have been devastated by the coronavirus, while others have been able to halt the spread of the disease. In New York City, for example, high population density and high workplace density both contributed to the spread of the virus. Additionally, New York’s population preconditions (high incidence rates of heart disease, cancer, and chronic respiratory disease) in addition to its high population health risk (based on age, education level, and income) make America’s biggest city a hotbed for pandemic illness. The index can even help explain why Florida didn’t become “the next New York.” A healthier and less dense population, in addition to a lower rate of workplace interactions, can help explain why the sunshine state was largely spared from the scourge.

The insights of Emsi’s Health Risk Index can help any city analyze its coronavirus risk and prepare an appropriate response. For example, Emsi researchers recommend that cities with high population density “focus on protecting dense, high-traffic areas.” This can include reducing the number of riders on public transportation and regularly sanitizing high-traffic areas. Similarly, cities with a high level of workplace interaction can divide shared workspaces to limit interaction or require employees to work remotely.

Coronavirus has brought in its wake unique challenges as countries struggle to keep their populations safe. Better data analysis can help countries enact better virus-prevention and virus-containment policies. As states grapple with the possibility of a second wave of coronavirus cases, metrics like Emsi’s Health Risk Index can help all states prepare a strong government response that can be vital to saving lives.